Yesterday you might have read Modern Art Notes’ post on artist Robert Fontenot’s Recycle LACMA project, in which the artist purchased deaccessioned objects from LACMA’s collection and refashioned them into new objects (also mentioned in a couple of other blogs). Some of our curators have also been thinking about the many issues surrounding Fontenot’s project—there’s a lot to unpack. We asked our curator of contemporary art, Rita Gonzalez, for her thoughts.

It’s been forty years since Andy Warhol transformed the collection of the Rhode Island School of Design in his curatorial effort Raid the Icebox I. Hanging an assortment of scuffed Windsor chairs on the walls salon style and stacking multiple shoe boxes culled from the forgotten parts of the museum’s collection, Warhol shined a light—literally—on the leftovers (a category that attracted him to objects and people alike). Conjured up from the same font of inspiration, Los Angeles-based artist Robert Fontenot’s online project Recycle LACMA continues this conversation about what remains hidden and what merits display in museums today—and just who is involved in that conversation.

Ironically, Fontenot first started thinking about the lifespan of the museum object when he interned at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum of Art, where he worked with LACMA’s former decorative arts curator Thomas S. Michie. As a self-confessed packrat working within a collecting institution, Fontenot found himself thinking about which objects were being preserved and which were contenders for deaccession. The hoarder in his head wondered, “just because this object is not needed now does not mean it won’t be 100 years from now.” This interest in the discarded translated into his artistic practice as he started to work with outmoded craft techniques, such as the incredible assortment of embroidery samplers that can be viewed on his blog Dictionary of Earthly Delights.

Earlier this year, Fontenot acquired fifty objects from three different auctions of deaccessioned materials from LACMA’s Costumes and Textiles collections and has undertaken the self-imposed task of repurposing each into an altogether different entity.

James Galanos Long Coat

Car Seat Cover

Rather than a condemnation of deaccessioning practices, Recycle LACMA is a joyful but biting call to all collecting museums to think more radically about re-circulating these objects back into a creative economy. While the texts that accompany the deaccessioned and detourned costumes and textiles on his blog comport with the language of museum recordkeeping (condition reports, justifications for deaccessions), this simulation of the institutional voice is only one facet of his project.

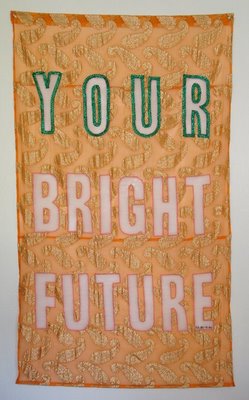

The other, more ludic aspect concerns the potential of curators and registrars to think in an expanded way about recycling cultural materials back into a chain of production. Fontenot acknowledges in short essays interspersed throughout the blog that LACMA (as do most museums) looks for cultural institutions more suited for the objects on the deaccession list. But rather than delving too deeply into the pedantic, Fontenot exerts more of his obsessive energy into breathing new life into his acquisitions (which ironically involves “killing” the old object and thus rendering them ineligible for that one hundred year retrospective!). He turns a gold lamé paisley skirt into a promotional banner for our present exhibition Your Bright Future. A 1950s evening dress becomes a beach umbrella. And while the embroidered pair of Guatemalan pants reborn as teddy bears makes some giggle, the Claire McCardell dress morphed into a witch’s cap might make some cringe. Of course, those reactions indicate another type of devaluation of the nameless artisan versus the auteur.

Paisley Skirt

Banner for "Your Bright Future"

As I sat and discussed the project with our Costume and Textiles curator Kaye Spilker, she wondered aloud if it is the status of her department’s holdings—so undervalued from the standpoint of art history—that made them more available to Fontenot. Would Fontenot have turned a Van Gogh drawing into a witch hat? As I continue to sit and grapple with this provocative project, I wonder in the end if what Warhol and Fontenot allow us to think through is how the curator and artist are the collectors and hoarders who are oftentimes forced to create through purging and construct through deconstruction.

Rita Gonzalez