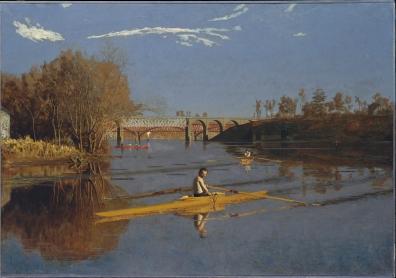

Thomas Eakins, "The Champion Single Sculls (Max Schmitt in a Single Scull)," 1871, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, The Alfred N. Punnett Endowment Fund and George D. Pratt Gift, 1934

You wouldn't think that I, a lowly LACMA volunteer, would have anything in common with Thomas Eakins, the greatest American realist of the nineteenth century. I like two-for-one sales and cats; he was more into dissecting horses and organizing nude photo shoots. Also, I can’t paint. Yet I think we share a common trait, Eakins and I: perfectionism.

Eakins found it hard to cope with failure. Whilst studying in Paris he sent home frantic letters to his father promising to become a better painter. He had two nervous breakdowns in his lifetime: one following the death of his mother, whom he had “failed” to nurse back from mental illness; the other was after his dismissal from teaching (due to alleged “misconduct”). Some might say he overreacted.

Perfectionists always do. Subject to polarized thinking (seeing situations/people as either “wonderful” or “awful”) the perfectionist crafts a self-oriented world that either helps or hinders them in their quest for the ideal. If the latter, the perfectionist dreams up scenarios in which everything turns out right.

For Eakins, this meant that his drawing master, Leon Gerome, was “raised above the swine,” whilst his Philadelphian detractors were compared with an “evil person.” It meant creating “enchanted” worlds in his art: rivers, woodland grottos, sports arenas. Even his infamous “surgery” paintings feel like a magic show.

But the driving force of the perfectionists’ anxiety is that, deep-down, we know wishes don’t come true—at least, not as we imagine.

This explains why, in his paintings, Eakins turned his frustrations on himself. In The Gross Clinic (1875) his bloody body lies passive on the operating table. In The Champion Single Sculls (1871) Eakins, seen rowing in the distance, is a towering emblem of male strength and self-reliance. But look closely at his reflection: this fantasy is cut through by a gash of paint slicing the body.

I struggle with my own, more mediocre, self-destructive tendencies. (Will I EVER get to the gym?) But, whilst perfectionism can be a difficult character trait to live with, it can also birth greatness. Eakins’s work is testament to the fact that it’s okay to aim high... just so long as we can allow ourselves, and the world, to occasionally fall short.

Olivia Chapman