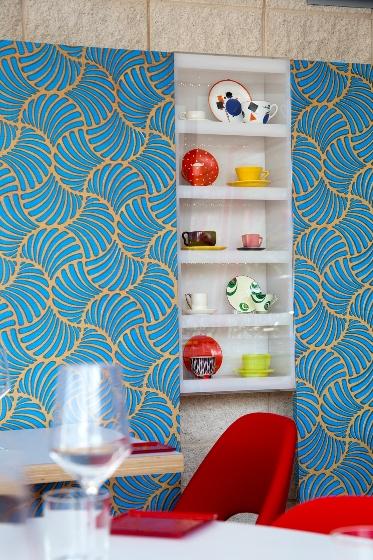

In developing the design for Ray’s, LACMA’s newest restaurant, Renzo Piano envisioned simple modernist architecture imbued with the character of its surroundings. Nature, urban spaces, the strength of LACMA’s art collection and the modernist pursuit of incorporating beautiful things into everyday life form the backdrop of the dining experience. The furniture and fabrics reflect the classic midcentury style of designers such as Charles and Ray Eames and Eero Saarinen, whose work is in LACMA’s collection. You’ll also notice teacups on display in the restaurant—part of the extraordinary Ellen Palevsky Cup Collection of over 150 cups spanning 1850–1950.

Teacup installation at Ray's

Many of these cups were produced by studio artists and by companies that employed the leading designers of the period, some based in California cities, including Los Angeles. Here is a peek at just a few of these cups.

Josef Franz Maria Hoffmann, designer; Wiener Porzellanfabrik Augarten, manufacturer, Teacup and Saucer, 1929, gift of Max Palevsky

Echoing the energy of LACMA’s architectural elements painted “Renzo Red,” Austrian architect and designer Josef Hoffmann’s boldly designed red and black teacup and saucer represent the force of the Vienna Secession, a late nineteenth-century design movement that sought to replace poorly manufactured, lackluster domestic objects with functional designs of beauty that were handcrafted with quality and yet still fulfilled the need for both utility and affordability. Hoffmann, a Secessionist founder, went on to establish the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshops) in 1903 and stated that “usefulness is our first requirement, and our strength has to lie in good proportions and materials well handled.” This colony of workshops produced impeccably crafted, everyday objects that Hoffmann asserted were “to be measured by the same yardstick as that of the painter and the sculptor.” Hoffmann also believed in a release from historic design, stating, “To the age its art, to art its freedom.” These words underscore his belief that art need not copy the past but rather reflect present-day styles. Freed from historical constraints, Hoffmann abstracted his designs into simple geometric forms.

Keith Day Pearce Murray, designer; Wedgwood, manufacturer, “Annular” Cup and Saucer, c. 1934, gift of Max Palevsky

With the turn of the century in 1900, the profession of designer was recognized as distinct from that of an artist, and designers looked upon themselves as capable of creating functional objects with aesthetic integrity that improved quality of life. Inspired by a visit to the 1925 "Exposition des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes" held in Paris, Murray designed a line of modern glassware that attracted the attention of Josiah Wedgwood V, managing director of Wedgwood from 1930 to 1968, who invited him to design for the company. Murray first collaborated with a team of designers that developed the "Annular" service, a line characterized by its distinctively modernist style, featuring ridged architectural earthenware bodies in matte glazes. Murray went on to create a series of functional vessels with simple and elegant forms with a thoroughly modern aesthetic; his elegant designs were popular throughout Europe and gained him the status of a renowned industrial designer. Due to the enduring popularity of Keith Murray's designs, they remained in production throughout World War II and formed a large part of the Wedgwood catalogue of glazes and shapes from 1940 to 1950.

Morris B. Sanders, designer; Gladding, McBean and Company, manufacturer, “Metropolitan” Cup and Saucer, c. 1950, gift of Max Palevsky

A little closer to home, the architect and industrial designer Morris Sanders developed the “Metropolitan” line of ceramics for California-based Gladding, McBean and Company, which still continues its operations in Lincoln, located in the metropolitan area of Sacramento. Established in 1875, the company thrived, producing ornamental garden pottery, chimney pipes, architectural terra cotta facades, and clay tile, including that which covers the roofs at Stanford University—the firm continues to provide the institution with roof tiles for campus additions.

Otto Natzler and Gertrud Amon Natzler, Cup and Saucer, c. 1942, gift of Max Palevsky

The turn of the twentieth century brought about two significant changes in American studio ceramic production. Ceramics came to be seen as a purely aesthetic art form that did not necessarily need to be functional. With this change of purpose came the emergence of the studio potter, who was involved in all phases of production including clay preparation, shaping, decorating, glaze formulation, glazing, and firing. As the focus shifted from commercial production to the idea of potter as artist, accredited schools implemented ceramics education programs that stressed a balance of technical proficiency and an aesthetic that unified form, ornamentation, and glaze. Studio potters experimented freely. They were also stylistically influenced by Asian ceramic traditions, the English Arts and Crafts movement, and modernist European styles. Countering the calculated precision of machine-made ceramics, the studio potter embraced the evidence of the artist’s hand upon a unique creation. By the mid-twentieth century, American ceramics had developed along many lines and expanded in multiple directions to create works representing America’s diverse culture and reflecting the energy that the country’s leading ceramicists brought to the art form.

Fleeing their native Vienna as the Nazi forces advanced toward Austria, studio potters Otto and Gertrud Natzler arrived in America with their potter’s wheel, kiln, and little else. They set up a studio in Los Angeles and their work was shown at the Los Angeles County Museum of Science, History and Art in the same year. The Natzlers’ ability to persevere and succeed with little training and few assets fueled what would become a nearly forty-year collaboration that combined Gertrud’s elegant and classically formed ceramic vessels with Otto’s multifaceted glaze formulations and firing techniques. With less than a year of training, Otto describes the couple’s beginning years: “Our lack of knowledge went hand in hand with a lack of inhibitions.” Their continual experimentation with materials and methods led to wafer-thin vessels that glow with vibrantly hued glazes.

Elizabeth Williams, Marylin B. and Calvin B. Gross Associate Curator, Decorative Arts and Design