I am often surprised by the subtle connections that can be drawn between LACMA’s exhibitions. Just yesterday I headed to the Pavilion for Japanese Art to see Fracture: Daido Moriyama, the first museum exhibition in Los Angeles devoted solely to the Japanese photographer best known for his gritty depictions of Japanese city life. The exhibition features black-and-white photos from early in Moriyama’s career, as well as some of his more recent color photographs.

Having travelled to Japan a couple of years ago, I was curious to compare my own memories of Tokyo and Shinjuku with Moriyama’s images. To me, while chaotic, most of Tokyo is the pinnacle of order, efficiency, and cleanliness. Where I visited, there was barely a single piece of trash on the street and not a single person coughed in public without attempting to cover his or her mouth. As I mentioned, certain areas were certainly chaotic—Shibuya, in particular (think those gigantic crosswalks where hundreds of pedestrians swarm into the intersection from every direction)—but even that frenzy is reined in by an impulse toward order (red hand means stop and they stop).

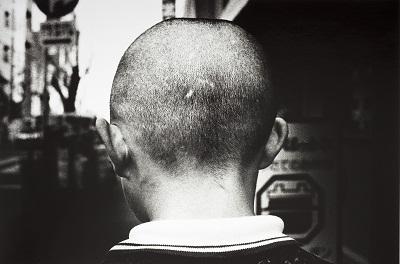

Street, Tokyo, Japan, 1981, the Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser Collection of Photographs, courtesy Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser, © 2012 Daido Moriyama

I ended up having a much more visceral response than I expected to Moriyama’s images. The textures in his photos—the fuzz of a young boy’s buzz cut, water splashing off of the scales of fish that are systematically being pulled from the water by an industrial fishing line—left an existential grit on my skin, in my mouth. I could taste the saltiness of the tears of post–World War II Japan; I could feel the smog in my lungs, the grease on my fingers of defiant and rapid industrialization/westernization of a country determined to bounce back.

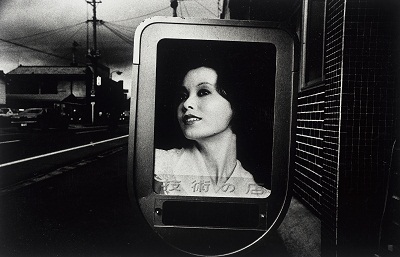

Daido Moriyama, Beauty Parlor, Tokyo, c. 1975, Ralph M. Parsons Fund, © 2012 Daido Moriyama

Truthfully, it almost became too much for me to bear . . . until I came across two photos. The first is one called Beauty Parlor, Tokyo (c. 1975). The photo appears to be a close-up of a beauty parlor advertisement: a radiant Japanese woman—skin and blouse blazing white—set against a dark, dirty street, the black-dusted sky crisscrossed by low-hanging power lines. While, in theory, this is the ultimate cynical statement about the westernization of Japan—the emphasis on production and economic growth veiled only slightly by the western ideal of beauty—I still found this photo to be oddly stimulating. That girl looks fun. She looks like she would appear in a Haruki Murakami novel hanging out in a jazz club with a talking cat.

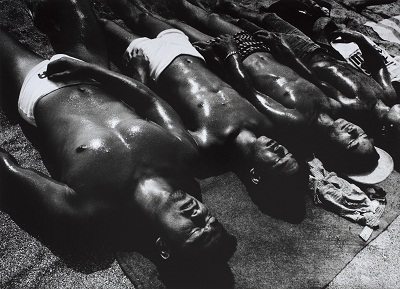

Beach Boys, Zushi, Japan, 1967, printed 2009, the Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser Collection of Photographs, courtesy Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser, © 2012 Daido Moriyama

The second photo that lifted my spirits is called Beach Boys, Zushi, Japan (1967). I was immediately drawn to this photo. For one, it’s fairly large—hard to miss. But the composition of the photo is also alluring. The men's bodies are reclined at the same angle on the beach, each body glistening. It's almost as if their bodies have been lapped up onto the beach by waves—handsome fish beached on the shore. I also like this photo because these guys remind me of the Japanese men in my life—my father, my grandfather who passed away last week, and my father-in-law. All three of them were good-looking chaps during that era, if not in a Japanese-boy-band kind of way.

Mary Ann DeWeese, for Catalina Sportswear, California Lobster Bikini, Man’s Shirt and Trunks, 1949, collection of Esther Ginsberg/Golyester Antiques, © 2011 The Warnaco Group, Inc. All rights reserved. For Authentic Fitness Corp., Catalina Sportswear

As I pondered these Japanese men in their fashionable swim trunks, another LACMA exhibition came to mind: California Design, 1930–1965: “Living in a Modern Way.” With Moriyama’s postwar psychological burden placed firmly on my shoulders, I walked over to the Resnick Pavilion for some levity. Maybe in my mind I thought I could make a connection between these sunbathers in the land of the rising sun and the Catalina Sportswear bathing suits that are featured in the exhibition.

Installation view, California Design, 1930–1965: “Living in a Modern Way,” October 1, 2011–June 3, 2012, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, photo © 2012 Museum Associates/LACMA

The exhibition itself is light, airy, and colorful, with the clean lines of mid-century design and a mix of wood, metal, and textiles (it closes June 3 btw!). My first, if not misguided, thought was, “Wow, this is how the winners prospered!” What I meant by that is that postwar America—in this case California—seemed to really embrace the hope that the defeat of Germany and Japan in World War II brought. It was an extraordinary time in the history of California art and design. People took advantage of the ramped-up domestic economy and industry to create some astonishing things—to create a distinct style and lifestyle that they exported (Japan imported its fair share, no doubt). Obviously other things were going on that made this era so lush with creativity in California. However, to me, juxtaposing the two exhibitions helps to contextualize the time and place of the artists in each.

None of this is to say that Japan was all gloom and doom. The Japanese created some extraordinary art during that time—I think that it just germinated from a different philosophical seed than that of California artists. But don’t take my word for it: Check out Fracture: Daido Moriyama for yourself, which is on view through July 31. Also, LACMA is presenting a film series, High and Low: Postwar Japan in Black and White, along with the Fracture, starting tomorrow night through Saturday, and then it picks up again June 8–9.

Jenny Miyasaki