The first of LACMA’s various film series presented in conjunction with Stanley Kubrick, 2012: A Kubrick Retrospective is a complete survey of the director’s oeuvre. Screening in chronological order, this retrospective allows viewers the opportunity to consider how Kubrick’s style progressed over forty-five years of filmmaking. Perhaps no other American director since Orson Welles realized a body of work so uncompromising in its artistic ambitions yet so grand in scale within the studio system. Kubrick not only pushed cinematic technologies and conventions into uncharted territories but he also changed the public perspective of the Hollywood auteur.

[youtube=http://youtu.be/lTU4UIHw-x4]

Born in 1928 to a secular Jewish family in the Bronx, Kubrick was a chess prodigy, avid reader, poor student, ardent cinephile, and, at seventeen, a published photographer. He never completed college. His early short documentaries developed as an outgrowth of his work for Look, the magazine that first published his images when he was still a teenager and went on to assign him shoots all over the U.S., leading to some nine-hundred images being printed within their pages in just a few years. These three shorts offer carefully observed, photo-realist portraits of people performing dangerous occupations—a boxer, a priest who administers his rural parish by plane, and unionized mariners—and the somewhat surreal worlds they inhabit.

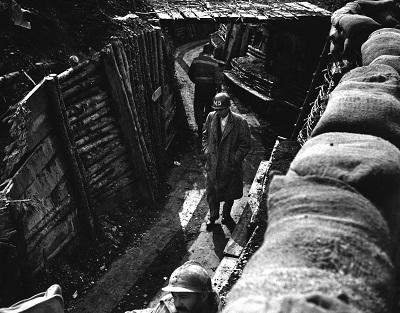

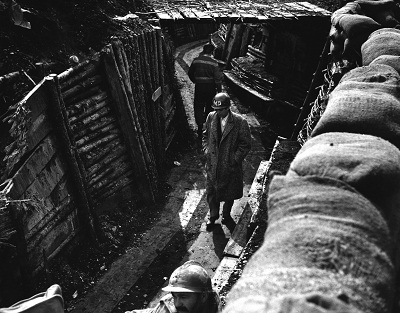

Stanley Kubrick on the set of "Paths of Glory," directed by Stanley Kubrick, 1957, © Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc.

[youtube=http://youtu.be/nmDA60X-f_A]

Kubrick largely disowned his first-feature, the independent film Fear and Desire which he shot in the San Gabriel mountains, about soldiers trapped behind enemy lines, though many of its themes and tropes would recur in future Kubrick films, such as the use of voice-over, the encroachment of madness, the outbreak of senseless violence, the limits of indentured servitude, natural light cinematography and the tension of entrapment within a forbidding landscape. But perhaps most prescient is Kubrick’s dominance of key aspects of the film’s production: he directed, shot and edited Fear and Desire. Though he wouldn’t receive such credits in subsequent motion pictures, Kubrick would continue to command every facet of his major films.

[youtube=http://youtu.be/HcIMY1Ah3aw]

Kubrick subsequently directed a pair of artful film noirs—one shot in New York, the other in Los Angeles—and an equally minimalist and piercing war film—Paths of Glory—before turning his formidable skills to filmmaking with bigger budgets—the epic period picture Spartacus, shot in Super Technirama 70 and color.

[youtube=http://youtu.be/zRVqgvW8100]

The two black comedies that cemented his rank atop the new generation of major motion picture directors—Lolita and Dr. Strangelove: Or How I Stop Worrying and Learned to Love the Bomb—set into motion a career like few others in film history. Though he only completed six features in the ensuing three decades, each of them can easily stand on its own as exemplifying Kubrick’s singular modernist vision, which blends individualism and terror, grand production value and abstract concepts, photorealism and the grotesque, technology and the irrational, fastidious craftsmanship and psychological trauma, and lust and conscription. Each film has been studied, admired, reviled, and copied in equal measure.

[youtube=http://youtu.be/1gXY3kuDvSU]

A cerebral filmmaker who researched meticulously for his major works, Kubrick maintained control of every detail from preproduction through a film’s release. And whether setting his films in the trenches of the Vietnam War, the hinterlands of the American Southwest, or the furthest reaches of space, Kubrick would work from the 1960s onward in England. Not quite an exile but rather an expatriate, he made major studio pictures while never venturing more than a few hours’ drive from his home. Though many of his works were met with some confusion or even outright hostility during their initial releases, they have become touchstones for film goers, filmmakers, academics, artists, musicians, writers, and mass culture alike. To many, they define the essence of modern cinema.

Bernardo Rondeau, Assistant Curator, Film

Presented with the generous support of Warner Bros. Special support provided by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.