Ed Ruscha first drew the Hollywood sign in 1967. Since then, the familiar icon has appeared in many of his paintings, drawings, and prints. Although he has joked that the sign was “a smog indicator: If I could read it, the weather was OK,” its recurrence in his art hints at Ruscha’s deep, personal engagement with film and film culture. I traced some of these connections while preparing the exhibition Ed Ruscha: Standard.

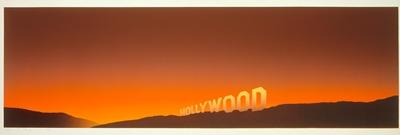

Ed Ruscha, Hollywood, 1968, Museum Acquisition Fund, © 2012 Edward J. Ruscha IV. All rights reserved. Photo © 2012 Museum Associates/LACMA

Ed Ruscha, Hollywood, 1968, Museum Acquisition Fund, © 2012 Edward J. Ruscha IV. All rights reserved. Photo © 2012 Museum Associates/LACMA

Ruscha vividly recalls seeing Hollywood films at the local theater while growing up in Oklahoma. When he moved to Los Angeles in 1956, he became more immersed in cinema. Among the films he recalls from that time are Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory (1957) and Joseph Strick’s The Savage Eye (1960); he also saw foreign films and silent classics at the Vagabond Theater on Wilshire Boulevard near MacArthur Park.

The early 1960s brought about an exciting convergence of young Hollywood and the artistic avant-garde. Ruscha entered these circles and became friendly with Dennis Hopper, Dean Stockwell, Harry Dean Stanton, Toni Basil, Teri Garr, Walter Hopps, Bruce Conner, Wallace Berman, Stan and Jane Brakhage, Jonas Mekas, and many others. He was at the Hollywood party that Hopper threw for Andy Warhol when the Pop art star made his first visit to Los Angeles in 1963.

By the late 60s and early 70s, Ruscha was making his own films: a self-referential documentary of sorts titled The Books of Ed Ruscha (1968–69, unreleased), followed by the narrative films Premium (1971) and Miracle (1975), both on view in the current exhibition. While he enjoyed the experience of making these films, Ruscha didn’t take them too seriously. He remarked in 1973, after attempting to find distribution for Premium: “Some artists make films that are an end in themselves…they’re statements. Mine’s not like that. I don’t want people to look at the film like it’s a deep statement on my part. It’s just an excuse, the story, to make a movie…. I don’t know where the movie fits in anywhere, and I can’t place it in my art at all.”

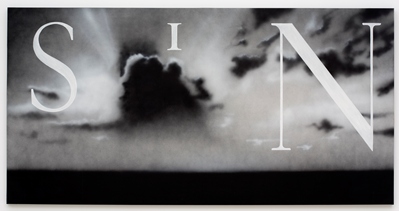

Ed Ruscha, Sin/Without, 1990, purchased with funds provided by the Modern and Contemporary Art Council and the National Endowment for the Arts, © 2012 Edward J. Ruscha IV. All rights reserved. Photo © 2012 Museum Associates/LACMA

Ed Ruscha, Sin/Without, 1990, purchased with funds provided by the Modern and Contemporary Art Council and the National Endowment for the Arts, © 2012 Edward J. Ruscha IV. All rights reserved. Photo © 2012 Museum Associates/LACMA

Although Ruscha’s movies might not fit into his art, he and his art did find their way into several movies: he created title designs for Mel Damski’s Yellowbeard (1983), had a small role in Alan Rudolph’s Choose Me (1984), and the painting Sin (now in LACMA’s collection and on view in the exhibition) had a bit part in Michael Tolkin’s The New Age (1990). Cinematic motifs continued to proliferate in Ruscha’s work as well, for example a series of prints and paintings depicting film leader, surplus, filler, and tails, inspired by the “flaws and scratches” in old movies. More recently Ruscha appeared in Frontier, a film by artist Doug Aitken (2009), and last year he was the subject of a tribute by Lance Acord on the occasion of LACMA’s Art+Film Gala.

[vimeo http://vimeo.com/52477469]

In 2009, Ruscha curated a film series in conjunction with a major exhibition of his work at the Museum Ludwig, Cologne. For anyone who wants to update their Netflix queue, Ruscha’s suggestions are:

- Island of Lost Souls (1932), director Erle C. Kenton

- Bringing Up Baby (1938), director Howard Hawkes

- Grapes of Wrath (1940), director John Ford

- The Ox-Bow Incident (1943), director William Wellman

- Sunset Boulevard (1950), director Billy Wilder

- Try and Get Me (1950), director Cy Endfield

- Night of the Hunter (1955), director Charles Laughton

- Paths of Glory (1957), director Stanley Kubrick

- The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), director Jack Arnold

- Private Property (1960), director Leslie Stevens

- Cul de Sac (1966), director Roman Polanski

Britt Salvesen, curator and department head, prints and drawings department and Wallis Annenberg Photography Department