Frank Herrera, photograph of The Perfect Moment protest, June 30, 1989, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. © Frank Herrera

Frank Herrera, photograph of The Perfect Moment protest, June 30, 1989, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. © Frank Herrera

How did the Corcoran protest come about? Whose idea was it and how did you get involved?

A number of artists and curators got together at the Washington Project for the Arts to discuss the canceling of The Perfect Moment exhibition by the board of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, and to come up with ideas about how we might respond. My friend Andrea Pollan (at the time the Director of the Wentworth Gallery in Washington, DC) said we should project the pictures onto the wall of the Corcoran. Of course everyone was very excited and supported the idea. My primary responsibilities were PR and fundraising. Before the event, the Washington Post and the New York Times published articles explaining the demonstration and how the images would be shown. Shortly after the cancellation, a gay organization had a demonstration in front of the Corcoran, focusing on Mapplethorpe as a gay artist. Our arts organization focused more on Mapplethorpe as an artist with creative freedom.

Fundraiser event at the Collector Art Gallery and Restaurant, June 30, 1989. © Bill Wooby

Fundraiser event at the Collector Art Gallery and Restaurant, June 30, 1989. © Bill Wooby

Explain a bit about the process of putting the projection (and accompanying event) together. What needed to be done to pull this off?

First, we had Mapplethorpe catalogues from the exhibit at the Whitney Museum and from the Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia, and we chose photographs from those catalogues. Each image cost us $75 dollars to turn into a slide. We had to rent a projector from New York City, which was picked up by light and projection artist Rockne Krebs. In 1989 there were no digital projectors. If we had one, we could have shown the whole collection on the Corcoran by scanning each page. We created committees for different tasks such as postcard mailings, and contacting newspapers, TV and radio stations. We had just two weeks to organize our event!

Pat Buchanan, the radio talk show host, invited someone from our group to be on his show to talk about censorship and Robert Mapplethorpe. I asked if he had seen any Mapplethorpe exhibits, and, if not, I didn’t want to talk with him. We never heard back from him.

I received a number of obscene phone calls before the demonstration, saying things like I should be sent to hell for showing pornography. I also received a bomb threat one morning while I was at my restaurant, the Collector Art Gallery and Restaurant—the person warned that the bomb would go off in fifteen minutes. I went outside and waited fifteen minutes... when nothing happened I went back inside.

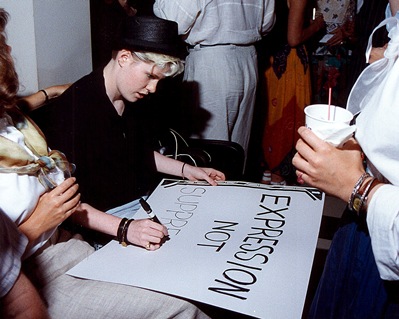

The evening of the demonstration, we had a fundraiser at the restaurant from 5 to 8pm. The date of the event was June 30, 1989, the same day that was scheduled for the original opening. We charged $25 per person for the event. We served hors d’oeuvres and drinks, and provided materials for participants to make their own protest signs. My personal favorite sign was one made by artist Kathleen Bober, “Free the Penis!” Around 8pm, we all got on buses that we rented and went to the Corcoran for the event. After the demonstration, participants went to galleries on DuPont Circle and R Street, NW, or back to the Collector to party until the wee hours.

Frank Herrera, photograph of The Perfect Moment protest, June 30, 1989, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. © Frank Herrera

Frank Herrera, photograph of The Perfect Moment protest, June 30, 1989, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. © Frank Herrera

Why this particular format—a projection? I've read some interpretations that the projected image of Mapplethorpe served as a kind of ghostly evocation—which is quite poignant given that he died only months before. Was the projection meant to carry this kind of symbolic weight? Who selected the images that appeared, and what were the criteria for selection? Did you purposefully avoid including the more sexually explicit images?

Rockne was the leader in choosing images with a group of artists. We only had so much money and we spent around $7,000 on this event including the buses, projector, and other things. I donated food and beverages from my restaurant. The first people who became upset about the Mapplethorpe exhibit cancellation were people from outside of Washington, DC. The first money donated to our cause came in from a man in Albany, who read about it in the New York Times and called me to find out more about it. The Robert Miller Gallery in New York (Robert Mapplethorpe’s dealer) donated $1,000, and others donated money as well. There was no support from the Mapplethorpe foundation. They thought it would take away from Robert's image—they didn’t want to focus on the negatives. We were told not to use any images of individuals. We received no criticism of the images we selected from the people who attended the protest. Our selections were based on our desire to showcase the wide scope of Mapplethorpe’s work. We didn’t make a point to avoid including the more sexually explicit images; it just worked out that way. Jesse Helms was upset before even seeing the images to be displayed. I think the only image he saw was the invitation which had biracial men showing affection.

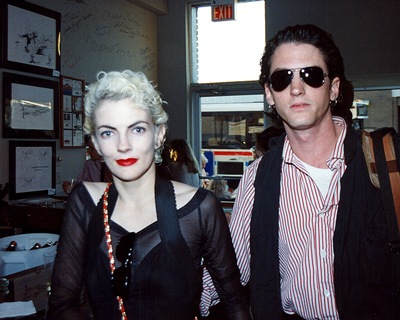

Melody with Edward Mapplethorpe, the Collector Art Gallery and Restaurant, June 30, 1989. © Bill Wooby

Melody with Edward Mapplethorpe, the Collector Art Gallery and Restaurant, June 30, 1989. © Bill Wooby

Who turned out for the event? Who was notably absent?

Andrea and I tried to contact different celebrities that Mapplethorpe photographed. Sigourney Weaver and Patti Smith and other celebrities did not want to get involved for personal reasons. Andres Serrano did not want to be involved because of what he went through with the National Endowment of the Arts and Jesse Helms. The people who did show up were Edward Mapplethorpe (Robert’s brother), Melody, and Harry Lunn (Mapplethorpe dealer in DC). Early on we did not expect many people to show up based on the verbal response I received from artists and dealers. One dealer said to me, "Why should I worry, my artists aren't gay," and another artist said, "Why should I care? I don’t get any money from the National Endowment of the Arts." There were other dealers at the time who were not supportive because they were worried about offending their Republican customers. I received a phone call from a gay organization called Act Up who wanted to know if they could come down and be part of the demonstration. I said yes. I received a phone call from another gay organization and I told them that Act Up was coming from NYC. When I told the woman about this, she became very worried and told me I should have insurance on my equipment. She told me that Act Up might destroy the equipment, destroy the Corcoran, or block traffic. I was very worried. This information came to me two days prior to the demonstration. I was very relieved that Act Up did not attend. We had gay and artist organizations that gave speeches at the demonstration and we had the projections. Cheers started when the photograph of Mapplethorpe was shown on the wall of the Corcoran. Reporters at the event said that they had not seen so much press in Washington for anything that was non-government related.

Christina Orr-Cahall received considerable negative attention for her decision to close the Perfect Moment exhibition. How did Orr-Cahall and the Corcoran respond to or get involved in this event?

Christina Orr-Cahall and the Corcoran board could have stopped us from creating the projection, but she let us use the property, close off the street, and project images on the building. I spoke to her ahead of time and she gave us permission. I give her a lot of credit because I feel that her story about the events leading up to the cancellation and events after has not yet been told. The NEA told me they could not support us but they were there for the event.

Frank Herrera, photograph of The Perfect Moment protest, June 30, 1989, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. © Frank Herrera

Frank Herrera, photograph of The Perfect Moment protest, June 30, 1989, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. © Frank Herrera

This event garnered a huge amount of attention at the time, including on the cover of the September 1989 issue of Artforum . What kind of response did you get, and how has it endured?

Out of all the photographs taken of the demonstration, we chose to use Frank Herrera's photos because he used a large-format camera. His photo of Robert Mapplethorpe’s portrait projected on the Corcoran Gallery building was on Artforum magazine and other publications around the world. The publisher of Artforum said that they sold more copies of that magazine than any other issue they had published.

The response to the demonstration was in general very positive. I received phone calls and letters from publications, radio and television stations from all over the world. They requested copies of Frank Herrera's photos. The event was well remembered—years later I still received letters and phone calls.

We did receive some negative response about the demonstration. I was asked to leave two galleries in Washington, DC because of my involvement in the demonstration. A couple weeks after the event, talk show host Phil Donahue showed Mapplethorpe photographs to the audience on his television show and asked them if they wanted their tax dollars to support the arts. The audience responded “no.” So I suppose we didn’t change everyone’s mind, although I think we made a lasting point.