Midway through the exhibition Hans Richter: Encounters, visitors come across a table on which stand four iPads with moving images on screen. Pick one up and you're suddenly looking at a complex art installation on screen, superimposed over the gallery space at LACMA. Move the iPad around and you find that the environment continues in every direction. Artists Will Pappenheimer and John Craig Freeman have re-imagined the so-called Russian Room of the famous 1929 Film und Foto (“FiFo”) exhibition in Stuttgart for which Hans Richter served as film curator. According to LACMA curator Frauke Josenhans, the FiFo show was a landmark in modern art, associating film and photography for the first time, and giving film the attention it deserved as a new art form. The leading Russian Constructivist, El Lissitzky, and his wife, Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, were commissioned to design the Russian Room, which was a totally unique environment created in order to display a selection of Russian photographs, film stills and film footage.

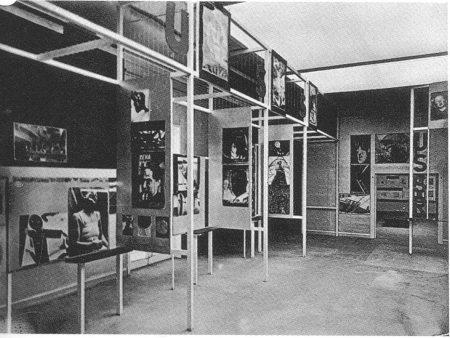

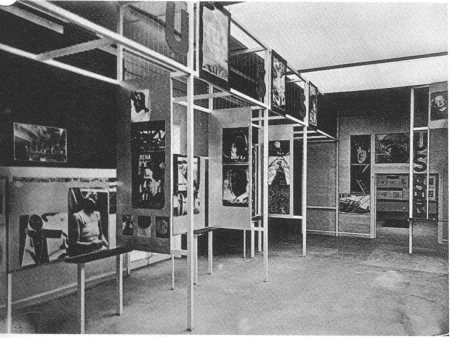

The Russian Room at the 1929 "FiFo" exhibition in Stuttgart.

The Russian Room at the 1929 "FiFo" exhibition in Stuttgart.

Using augmented reality, a technology that enables the creation of a 3-D visual environment within the field of vision of the camera, Will and John Craig have recreated and interpreted the extraordinary design of the Russian Room, with it's scaffolding and surfaces at various heights juxtaposing photography and moving images. They've also added some creative elements of their own.

Augmented reality installation by John Craig Freeman and Will Pappenheimer. (Easter egg spoiler alert: Will and John Craig appear at lower right.)

Augmented reality installation by John Craig Freeman and Will Pappenheimer. (Easter egg spoiler alert: Will and John Craig appear at lower right.)

If you want to see the piece in use in the gallery, watch this short video demonstration from John Craig.

This is Will and John Craig's second stint at LACMA; last summer, they participated in our Artist's Respond series with an augmented reality "intervention" called Project O-rator that you can still experience on our BP Pavilion. Curator Tim Benson saw that project during development and realized that augmented reality might bring to life the spirit of the FiFo Russian Room, documentation of which has largely been lost to history. And so our first in-gallery augmented reality experiment was born.

While Will and John Craig were installing the piece at the museum, we talked about the project. Here's what they had to say:

John Craig: We're interested in using emergent technology to invent new forms of public art. We’ve worked at museums before but ti was in an interventionist way – we’d go in without an invitation and people would show up with their cell phones without the museum knowing. But this project was a way for us to iron out the possiblilities within an exhibition, working with the curator. This is the first time a museum has been willing to take a risk on us like this.

Will: Hans Richter was working at a time when artists were embracing new technologies and engaging them within their work in order to explore what they signify. One of the things we really got into was the idea of expanded cinematic space, an idea that fascinated Richter and his contemporaries.

John Craig: We hope we’re demonstrating a continuous line of inquiry. The questions these artists were raising in the early 20th century are questions that aren’t by any means answered yet. For example, how do we invent a new visual language to respond to the emergent technology of our day? In the case of Sergei Eisenstein, the response to that question was to invent montage that eventually became the norm for how film constructs meaning. That same kind of inquiry needs to happen now with network communications and virtual forms of meaning and representation. What’s the new grammar of virtual space and social media?

Will: What will cinematic space be now? There is the idea of a collective space created by the internet that you move through at the same time as you move through the physical world. Whether or not it’s narrative is a discussion we should be having. Augmented reality can be very powerful if it has a narrative, but it doesn’t have to have a narrative, just as there is non-narrative film and video. It can be a spatial narrative, too, instead of linear narrative, as you move from one thing to another.

Augmented reality allows you to juxtapose two realities: what’s in the world and what’s in the augmented reality experience. I like to think about resonance; the object we’re putting there isn’t necessarily forming a narrative, it’s forming a resonance with what is there in the environment already. And that resonance can be dissonance. Everything doesn’t have to work together in a harmonious way.

In talking to Tim Benson about his research on Hans Richter and his contemporaries, we learned how those artists went to great lengths to see if they could destabilize the viewer’s perception going into an exhibit. That’s what the FiFo Russian room is about – you’re not sure what’s where. They wanted to destabilize space and create an immersive experience of encountering art.

What we’re doing is it is immersive too; it’s all around you. When people first pick up the iPads, they wonder what they’re seeing. There is a confusion about what space it is, and what's real.

John Craig: Being here in Los Angeles is special too. I took Will to the camera obscura in Santa Monica. It really impacted me as a kid and my need to engage with virtual reality. Painting is based on the camera obscura: representation requires a frame being made, and a point of view and the artists choosing to leave something in the image or not. What we’re doing departs from that; although the iPad has a frame, the experience is starting to get loose of the frame. The point of view is handed over to the audience, because you can walk through the space. Augmented reality is destabilizing the way we construct representation.

Amy Heibel