LACMA has just received the remarkable donation of Max Beckmann’s Bar, Brown (1944), a superb painting by one of the most prominent German painters of the 20th century. This masterful work comes from the most productive period in Beckmann’s career: 10 years spent in Amsterdam that must also be counted as among the most difficult and challenging years of his life. Beckmann had immigrated to Holland in 1937 immediately after Hitler’s speech against “degenerate” artists. Indeed he departed on the opening day of the Entartete Kunst (“Degenerate Art”) exhibition in which his work was vilified by the Nazis. By then there were some 30,000 Jewish and political refugees living or arriving in Amsterdam. His efforts to reach America thwarted, he remained in Amsterdam during the German occupation, departing for America only in 1947.

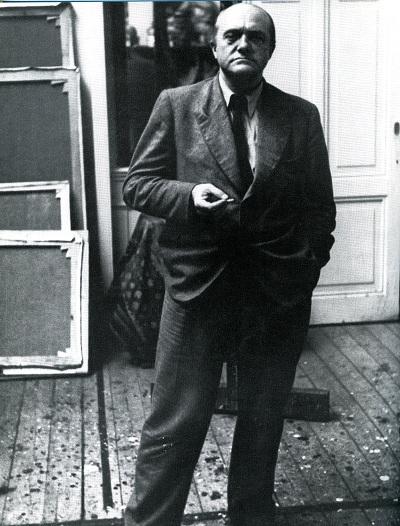

Max Beckmann in his studio, © Max Beckmann Estate, photo courtesy private collection/Helga Fietz-Franke

Max Beckmann in his studio, © Max Beckmann Estate, photo courtesy private collection/Helga Fietz-Franke

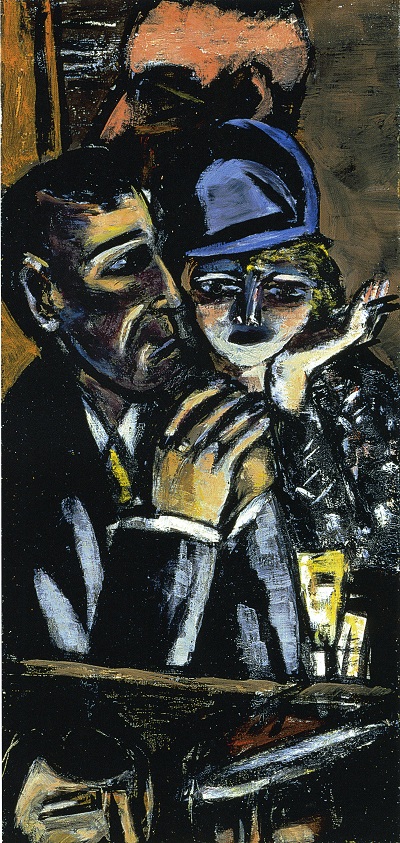

As seen in a photograph of 1938, he was able to paint in his studio during this time and could even exhibit his work in London, New York, Chicago, St. Louis, and various other cities throughout the United States, including Santa Barbara (thanks to the efforts of his friend and patron, the writer Stefan Lackner). Yet it was extremely difficult living in the impoverished conditions of occupied Holland. The situation was especially grim when this painting was done in 1944. The Dutch population was anticipating the liberation they had long hoped for now underway, but they also feared the casualties that might result should the battle move to Amsterdam. Bars and cafés provided release and entertainment and had become a frequent subject for Beckmann, what he called the “world theater” after Lackner’s suggestion. But by 1944 few bars were even open in a city where there were constant raids, deportations, changing curfew hours, and even confiscation of bicycles just as public transportation had ground to a halt for lack of fuel. Beckmann refers to having finished a painting called Bar Tivoli in a diary entry of August 8, 1944, and if this is that painting, the scene was probably at the bar at Reguliersbreestraat 26–28, an art-deco building of 1921 that contained the most luxurious cinema in Amsterdam, along with a cabaret and bar. The Tivoli name came from the German occupiers during WWII and provides a possible reason for renaming this location in the painting. The woman looking toward the viewer is certainly Beckmann’s wife, affectionately called Quappi. An aspiring opera singer when Beckmann met her, Mathilde von Kaulbach declined an offer from Dresden State Opera House, to marry Beckmann in 1925. Seated with her is Dr. Helmuth Lüthjens, with whose family the Beckmanns lived after the allied invasion of Holland in June by which time they had become entirely destitute. Representing the Amsterdam branch of Paul Cassirer’s venerable Berlin Gallery, Lüthjens had already brought most of Beckmann’s paintings into his house to protect them from possible confiscation. Many scholars suggest that the profile at the top of the painting may be Beckmann, who often appeared in his own paintings. The identity of the figures below remains mysterious. The brown tonalities are in striking contrast with other bar and restaurant scenes of this time, such as the brightly colored The Oyster Eaters of 1943, which also features Quappi.

Max Beckmann, Bar, Brown, 1944, © Max Beckmann Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG BILD-KUNST, Bonn

Max Beckmann, Bar, Brown, 1944, © Max Beckmann Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG BILD-KUNST, Bonn

Yet Beckmann’s broadly brushed paint strokes capture a bright artificial light perhaps originating from below the figures, which lends this striking painting an extraordinary emotional intensity. A certain lack of communication among the figures is typical of many of Beckmann’s bar scenes and may also suggest existential loneliness of the individual in the modern world, a frequent subject for Beckmann from the 1920s onward.

Beckmann’s ambiguous and elastic pictorial space is indebted to Paul Cézanne, whose art he had discovered while visiting Paris in 1903–4. In 1944, Beckmann, aged 60, was a robust painter at the top of his game, able to bring a mythic quality into his paintings that few other painters could match. Here he captured not only the entirely unique mood of Amsterdam at this time, but also something timeless, perhaps the human predicament in the modern world. Among the most directly engaging paintings of this period, Bar, Brown will be a destination painting in our modern galleries, where it now hangs between Beckmann’s bronze Adam and Eve (1936) and his Bridge and Wharf (1945). The painting is given in honor of the late Robert Looker, who served as a trustee from 1998 until his death in 2012 and was an especially astute collector of German Expressionism. The Lookers’ generosity has enriched LACMA and its collections broadly, with particular concentration in the Contemporary and the Costume and Textiles holdings.

Timothy O. Benson, Curator, Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies