Back in 1996, when I organized my first exhibition of Spanish colonial art in New York City, I included a group of fascinating works portraying racial types from Ecuador. The paintings were part of a set of six canvases, four of which had just been acquired by a private collector. The whereabouts of the two missing canvases was at the time unknown. Inscribed with the numeral 1 in the lower center, it was clear that this set was the first of two. The other series (bearing the numeral 2) is now in the Museo de América in Madrid and was shipped to Spain’s Royal Cabinet of Natural History in the late 18th century. It is signed by the Quito master Vicente Albán (active 1767–96).

LACMA’s recent acquisition of the two missing paintings from the first set is thrilling. What makes these paintings exceptional? To start, there were only two sets created of Ecuadorean racial types (in contrast to the over 120 sets of the popular Mexican casta paintings that I have identified to date). Striking for their meticulous portrayal of local bounty and combination of indigenous and European textiles and jewels, the works are also eloquent documents of the Hispanic Enlightenment.

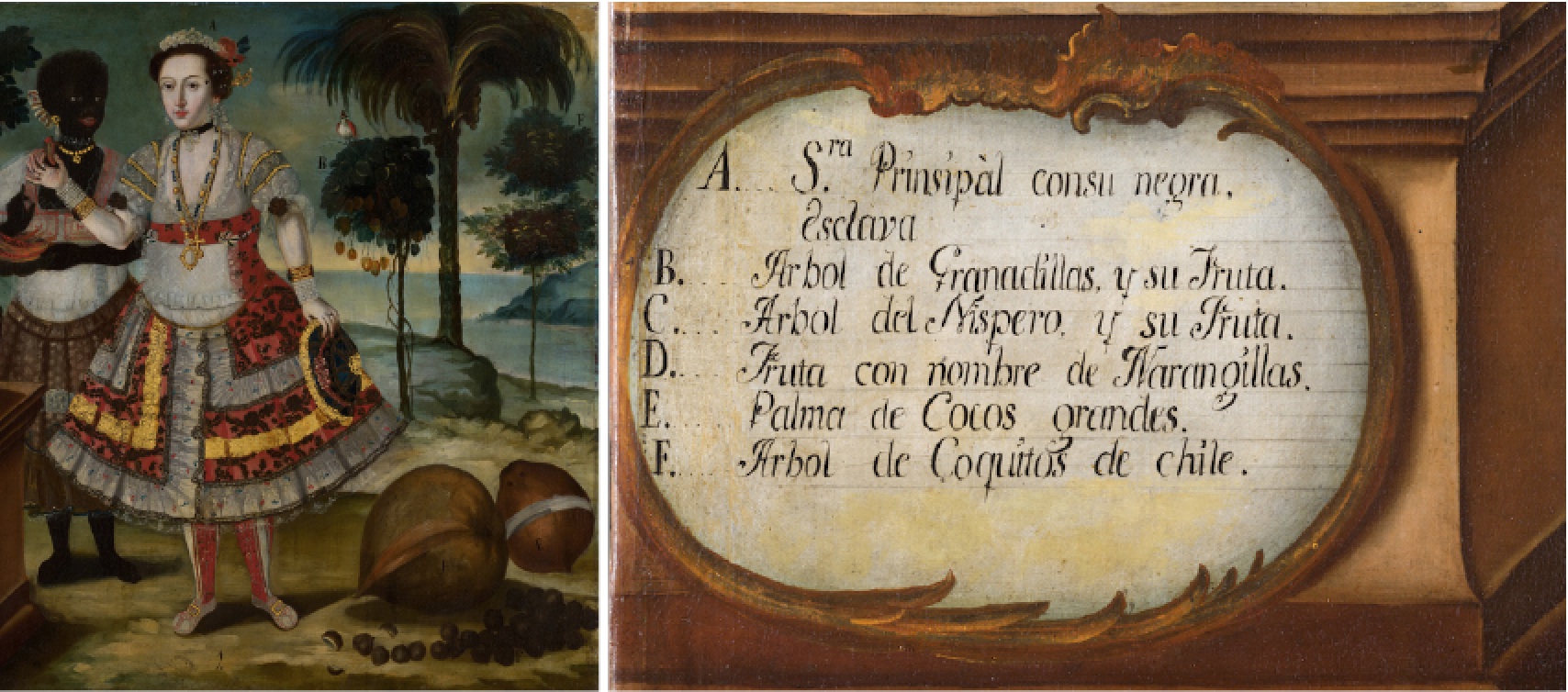

In Noble Woman with Her Black Slave, the white (or Spanish) woman wears an array of exquisite textiles, a string of pearls, and other jewels such as a gold crucifix and oval reliquary to signal that she is Catholic (and hence “civilized”). Her black slave (a conventional status symbol) is more modestly, if still lavishly, bedecked and is depicted barefoot. Worth noting are the “black” flowers of the noblewoman’s skirt and hat. Scientific analysis has shown that they were originally painted in silver—a feature that would have bolstered the image of the colony as a land of unsurpassable riches. Though now irreversibly tarnished, it is not hard to imagine the impact that the painting once caused, peppered with abundant touches of gold and silver.

In Indian Woman in Special Attire, ancient indigenous costume elements—including a tupu (metal pin) fastening her lliclla (shoulder mantle), a belt with tocapus (geometric motifs associated with rank), which was an essential part of a coya, or queen’s dress, and a small chu’spa (a bag to carry coca leaves that gave energy and staved off hunger)—are combined with elements of European dress, such as the lavishly ornamented lace collar and sleeves of her blouse. Noticeable, too, is the black fabric laid over her skirt, fastened with a black sash.

The X-radiograph clearly shows the large-sized pin, which is difficult to see due to the tarnishing of the metallic silver paint. It also reveals a delicate herringbone pattern on the woman’s mantle, now virtually undetectable to the naked eye. The pattern may suggest that this is a textile type known as tornasol (literally meaning “turns to the sun”). These shimmering silk fabrics were highly coveted in Europe and favored by the Spanish nobility. Colonial Andean weavers skillfully adapted them to their ancient textile traditions by combining a dark fiber warp (usually made of alpaca) and brighter contrasting weft (commonly silk). When the fabrics moved, they caught the light and created a glimmering two-tone effect. Contemporaneous travelers described this kind of pleated mantle as a distinct costume element worn by noble Indians.

One of the most salient elements of the paintings is the gigantic fruit placed next to the figures, making an explicit connection between the region’s inhabitants and its flora. The works convey a sense of American nature as extravagantly fertile. In Europe there existed the widespread idea that the Americas were an unusually hot place where nature and people—regardless of their racial makeup—ripened and spoiled quickly.

These paintings counter such notion by representing local types from Ecuador dressed in lavish clothing and standing next to an assortment of giant tropical fruits, emphasizing the abundance of the land. An elaborate key in the lower section describes the trees and fruits, directing the viewer to selected parts of the canvases. This technology of production and reception of meaning was amply used in New World pictures (though it was by no means exclusive to it) to render “difference” clear, transmit specific information, and reinforce the overall efficacy of messages.

Several scholars have linked the set at the Museo de América in Madrid with the Spanish botanist José Celestino Mutis (1732–1808), who led an important royal-sponsored expedition to the viceroyalty of Nueva Granada (1783–1816), and produced thousands of images of the region’s flora. (Nueva Granada refers to the Spanish colonial jurisdiction in northern South America, corresponding mainly to modern Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela.)

This would explain the equal emphasis lavished on the racial types of the region and the precise botanical renditions that show both the exterior and the interior of local fruits. Throughout the 18th century, the Spanish Crown sponsored a number of expeditions to the Americas to gain better knowledge of their natural resources and exploit them for commercial ends. The production of images became an inherent part of these Enlightenment-era imperial taxonomic projects.

Despite the scant information about Vicente Albán (who signed the Madrid set), we know that he often collaborated with his brother, Francisco (1742–88), and that they both were regarded among the most prominent Quito painters of the day. Mutis may have commissioned Vicente to paint the Madrid set as a gift for Madrid’s Royal Natural History Cabinet, which was established in 1771. LACMA's paintings, which are not signed, are very similar to the works in Madrid. But they also present intriguing formal and stylistic differences. The Madrid set, for example, is painted more freely and possibly by more than one hand, suggesting that it was created with workshop assistance. The figures in the LACMA pictures, on the other hand, seem to sit better in space and are more restrained in their handling of details (check back next week on Unframed to read more about the conservation process of these paintings).

It is likely that Mutis also commissioned the set to which LACMA’s paintings belong as a gift for another important patron who supported his expedition. It is important to keep in mind, however, that LACMA’s set also could have been commissioned by another Enlightened royal functionary that remains unidentified. Commissioning replicas was part and parcel of the culture of image making at the time, and it was not uncommon among Spanish functionaries to request copies of the same image. In addition, artists often copied their own paintings, which had an important place in their workshops.

Rich in detail, these two extraordinary pictures add an important dimension to our collection of viceregal art. A more complete study of the works will soon be published in a handbook of LACMA’s growing Spanish colonial collection.