Homosexuality was invented in Germany? While this might at first sound like a rather preposterous proposition, the idea of an identity based on a fixed sexual orientation did indeed originate in Germany. The public discourse and political movement supporting this idea also started in Germany, in Berlin in particular, and not, as one might assume, in London or New York. As Robert Beachy describes in his recent groundbreaking book Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity (2014), even the term HOMOSEXUALITÄT itself was a German invention, first appearing in a German language pamphlet in 1869.Although the origins of the movement date back to the 19th century, it was during the Weimar Republic (1919–1933), with its new social and democratic freedoms, that gay life experienced its unprecedented heyday. Despite the fact that sexual acts between men (women were simply not addressed) were still criminalized by Paragraph 175 of the penal code, homosexual men and women were able to express their identity more visibly than ever before. By the mid-1920s, around fifty thousand gays and lesbians lived in Berlin. With its countless nightclubs and meeting points for homosexuals, bisexuals, or transvestites, the city became a true “Eldorado” for this growing and vibrant community.

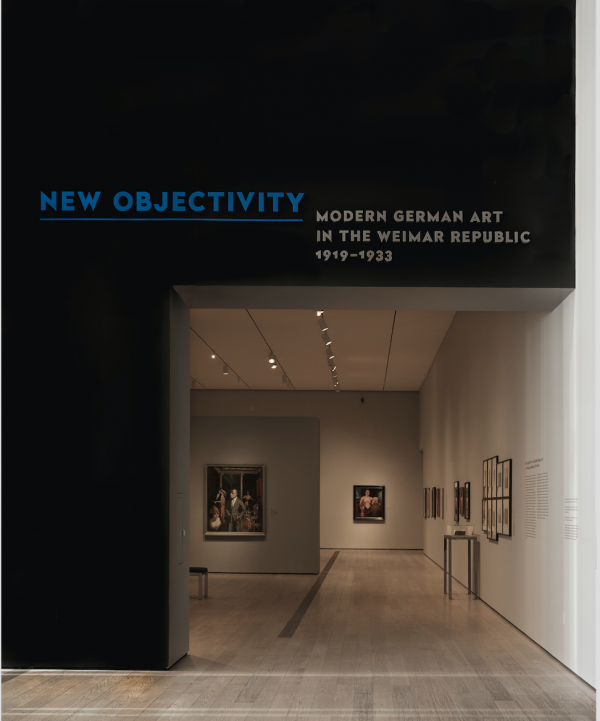

Our exhibition, New Objectivity: Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic, 1919–1933 (on view until January 18, 2016),devotes a whole section to these new social identities of the Weimar Republic. Here you will find stunning paintings and photographs depicting the so-called New Woman, with her bob, monocle, cigarette, and overall masculine demeanor, next to striking renderings of even more androgynous types, whose gender identity is ambiguous and even inscrutable at times. Look at Gert Wollheim’s Couple (1926), for instance, who might have come straight out of the popular nightclub Eldorado. With its transvestite hostesses, the infamous establishment attracted an illustrious crowd from all over Europe and featured performances by the likes of Marlene Dietrich. A contemporary visitor described the clientele of the famous cabaret as follows: “… you had lesbians looking like beautiful women, lesbians dressed exactly like men and looking like men. You had men dressed like women so you couldn’t possibly recognize they were men (…) Then you would see couples dancing and wouldn’t know anymore what it was.”

Or look at Christian Schad’s extraordinary Boys in Love (1929). This exquisite silverpoint drawing is a rare rendering of male homosexuality. The tenderness of the embrace is astonishing and congruent with the delicate subject matter. The loving intimacy between men so sensitively represented here seems even more provocative than a more explicit depiction of homosexual acts.

To illustrate the vast and far-reaching discourse surrounding the new identities of the Weimar Republic and to introduce the main protagonists defining and steering the movement, we are presenting books, magazines, and other ephemeral objects alongside the artworks. The vitrines in the exhibition include publications by the influential physician and sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, a pioneer and principal advocate of homosexual and transgender rights. The so-called “Einstein of Sex” founded the Scientific Humanitarian Committee, the first gay-rights organization and gathered more than five thousand signatures to overturn Paragraph 175. His prolific empirical research resulted in the publication of several anthologies examining gender and sexual identity and in the founding of the Institute for Sexual Research in Berlin, a museum, clinic, meeting point, and research center. There, in 1930, the first sex reassignment surgery in history was performed on Lili Elbe (previously Einar Wegener). This process is chronicled in the book Man into Woman, also displayed in the exhibition and the basis for the film The Danish Girl directed by Tom Hooper, which is currently playing in theaters across America.

,%201932,%20edited%20by%20Niels%20Hoyer,%20LACMA,%20photo%20Nana%20Bahlmann.jpg)

Shining a light on the various publications—over thirty at the time—for homosexuals, bisexuals, transsexuals, and transvestites, a selection of the most important gay and lesbian magazines is also presented in these vitrines. They include Der Eigene (The Unique), the first gay journal in the world. Published from 1896 until 1932 by Adolf Brand, it featured texts about politics and homosexual rights, literature, art, and culture, as well as aesthetic nude photography.

Der Eigene was followed by many other gay magazines like Friedrich Radzuweit’s Die Insel (The Island). Surprisingly, these publications were displayed publicly and sold at newsstands alongside other mainstream papers. They included advertisements and announcements for various kinds of nightspots and meeting points, catering to the respective preferences of their readers.

,%20Left%20to%20right%20June%201928,%20July%201930,%20April%201931,%20Schwules%20Museum,%20Berlin,%20photo%20Nana%20Bahlmann.jpg)

Throughout the 1920s, Radzuweit, who was also an important homosexual rights activist and author, established a publishing network for gay and lesbian magazines. In 1924 he issued Die Freundin (The Girlfriend: Journal for Ideal Friendship between Women), the first lesbian magazine, for instance, and later Das dritte Geschlecht (The Third Gender). After his death in 1932, his son Martin took over the business. Other lesbian magazines presented here are Liebende Frauen (Women in Love), and Frauenliebe (Women Love).

With Hitler’s assumption of power in 1933, the vibrant movement came to an abrupt and brutal end. The Nazis immediately raided Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Research and burned its archives. Wisely, Hirschfeld had not returned from a speaking tour and remained in exile until his death in 1935. Gay publications and organizations were banned and homosexuals were incarcerated, sent to concentration camps, or murdered; the Nazis eradicated the achievements and memories of this pioneering movement in Germany. We are happy to bring it back to life here in our exhibition at LACMA.