In 1975, David Bowie was living in Los Angeles, during which he starred in his first film (The Man Who Fell to Earth), crafted one of his best albums (Station to Station), and—by his own reckoning—lived like a paranoid vampire, legendarily subsisting on a diet of milk, red peppers, and cocaine.

Luckily, his survival instincts kicked in by early 1976, and he decamped for Europe. He eventually settled in West Berlin, where he produced a groundbreaking musical trilogy: Low (1977), “Heroes” (1977), and Lodger (1979). Both the title track and cover photograph of “Heroes” quickly came to epitomize Bowie’s new image as European art rocker. Long fascinated by German Expressionism, Bowie used the “Heroes” portrait—created in collaboration with photographer Masayoshi Sukita—to pay homage to painter and printmaker Erich Heckel. Heckel’s Roquairol (1917), which Bowie had encountered at the Brücke Museum in Berlin, was the primary inspiration for “Heroes”, the blank gaze and stiff posture of its subject (Heckel’s friend and fellow artist, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner) reinterpreted in Bowie’s own vacant stare and enigmatic hand positions.

Bowie had trained in dance and movement early in his career, so it seems natural that Kirchner’s intriguing pose in Roquairol would resonate with him. Additionally, at least two of Heckel’s woodcuts are known to have influenced the portrait, both of which are held in LACMA’s collection: A Disciple (1915) and Self-Portrait (1919). The former points as he speaks, while the latter folds his hands contemplatively against his chin. The following year, Bowie drew his own self-portrait after the “Heroes” cover, in a style that underscored his creative engagement with German Expressionism.

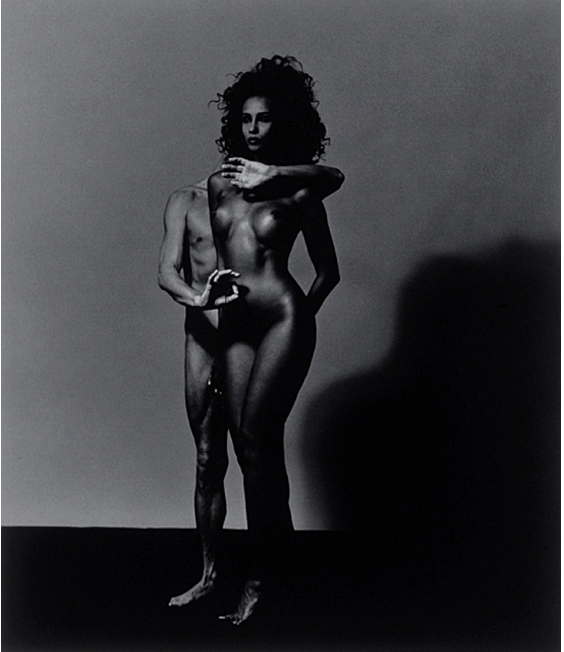

Nearly fifteen years later, both his fame and his striking looks were wittily effaced in Victor Skrebneski’s double portrait, Iman and David Bowie (1991), also in LACMA’s collection. Bowie stands behind Iman so that his head is completely hidden. His arms seem to emerge from her body, bodhisattva-like (a sense further conveyed by his hand gestures, which are evocative of Buddhist mudras as well as the “Heroes” portrait). Their legs are merged into a single set. The rock star and the supermodel are presented as a hybrid, otherworldly being, literally half-male and half-female, a visual realization of the fluidity of gender and identity that had first catapulted Bowie to fame in the early 1970s.

More simply, the image can be read as symbolizing the merger of their lives. At the time, Bowie and Iman had been a couple for about a year. Though his decadence may have reached its peak (or nadir) during his year in L.A., in fact Bowie had experienced virtually every rock n’ roll excess for two decades. By his own account, all of that stopped the moment he met Iman, and the couple settled quickly into a relationship that was renowned for its deep devotion and quiet domesticity. Perhaps this is why, in one of the earliest portraits of the couple, his face isn’t even visible. “David Bowie,” after all, was always a stage name—the overarching persona of the man who had made a career out of shifting personas. In Iman he had found the partner with whom he could be the one person he could keep private from the rest of the world: David Jones, himself.