Living for the Moment: Japanese Prints from the Barbara S. Bowman Collection showcases a wide-ranging collection. The gallery in the Ahmanson Building alone is filled with more than 50 prints from a broad array of ukiyo-e artists, and the exhibition continues in the Pavilion for Japanese Art. This comprehensive collection holds every style from the finest ukiyo-e artists in the 17th and 18th centuries. The pieces look quite ahead of their time, reaching a level of accessibility that one normally wouldn’t associate with Japanese art. I asked Hollis Goodall, curator for Japanese Art, why that would be.

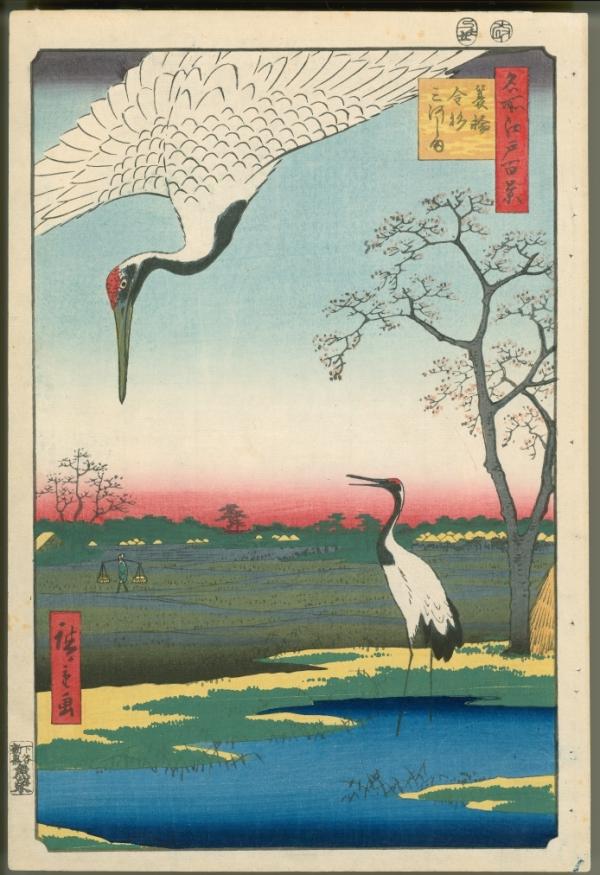

“It was considered to be, in its time, an art for the people. They were a means of communication about fashion, what was up-to-date in theater, the most recent plays, who was on top. I think people slowly have come to appreciate the artistry of them. And even in their own time there were certain artists whose publishers were willing to put out their designs with luxury pigments and mica backgrounds, so they had achieved enough popularity to be able to sell even the more expensive ones. People like Hiroshige were so popular that over ten thousand of a single image would have to be printed.”

Ukiyo-e prints were used for communication of news, mostly, and if the message couldn’t be written outright—such as with poems or references to current events—they were coded within the symbology of the artwork. Actors and courtesans went unnamed during particular periods, but the skilled reader could decode their identities through various visual clues. In a way, ukiyo-e was a proto–comic book style, with its widespread readership, low cost, and network of artists. Prints often had a team behind them, as do comics, with everyone from the artistic director or artist to the actual printers. It’s perhaps why a style that fell out of fashion over a century ago in Japan has had resonance in Europe and America since then; we’re used to the format.

Ukiyo-e was, in its time and soon after, too commercial to be considered anything other than utilitarian. But certain artists broke through the stigma and reached a higher level of artistry, and this is what the Bowman collection primarily includes; works that reached a higher resonance, and which were, and still are, considered art.

“With the introduction of western-style printing like lithography and etching, those prints that had been used for dispersing news stories lost their popularity quickly. So the artists that were left became less commercial artists and more fine artists, collectible artists. And there were only a few of them who survived that transition. That's kept going—the art for art's sake aspect—up to now. I think there's a stigma attached with ukiyo-e on the part of some Japanese connoisseurs that ukiyo-e print designers are not true artists, more illustrators. But some artists through their creativity and sophistication just reached beyond that level. So in those instances, ukiyo-e became an art form, and it's up to the collector to ferret out where the exceptional works of art are within ukiyo-e.”

Which is perhaps what makes this collection unique. From the vibrant colors to the detailed woodcut work—hairline cuts and gradient shading—the pieces are exquisite examples of the deeper artistry in ukiyo-e. And they do, to an extent, speak to our contemporary sensibilities of “communicative” art. We see examples of this style everywhere and every day, but never with quite so much artistic heft. The Bowman collection is certainly a chance for contemporary audiences to glean something about Japanese art in a way that’s rarely seen. We see the deepest dedication to the art form, one requiring focus and discipline; we see a connection to a history of Japanese printmaking, since “they started with illustration in books around 1604, and then became really popular as the 17th century progressed. At the end of the 17th and early 18th century, the prints began to leap off the page and become one-off illustrations that were sold separately.” The works demonstrate an elegance and mastery of the quotidian style, meant to visually entertain and inform the public.

“You understand what being a craftsman is in Japan. It's what [these artists] do and you can see how that allows a person to gain such an incredibly high level of skill, the kind of skill that went into making the highest level of these prints. It's really a serious matter for these [artists]. It's their path.”

Living for the Moment: Japanese Prints from the Barbara S. Bowman Collection is on view in the Pavilion for Japanese Art and the Ahmanson Building, Level 2, until May 1.