In 1928, the Mexican artist Federico Cantú (1907–1989) arrived in Los Angeles. Cantú had previously attended the Open Air School of Painting in Coyoacán, Mexico City, directed by Alfredo Ramos Martínez (1871–1946) (who also spent time in Los Angeles), assisted Diego Rivera (1886–1957) on his murals at the Ministry of Public Education in Mexico City, and studied sculpture in Paris with the Spanish artist José de Creeft (1884–1982). In February 1930, James Tarbotton Armstrong, curator of the University of Southern California Museum, arranged Cantú’s first exhibition of drawings and paintings at the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art in Exposition Park—LACMA’s parent institution. Though Cantú soon left for New York and Paris, and finally a return to Mexico, over the years he continued to visit Los Angeles, exhibiting his work at the Stendahl Galleries (late 1930s and early 1940s) and Lorser Feitelson’s Gallery of Mid-20th-Century Art (1948).

When Cantú returned to Mexico, he primarily devoted himself to painting neoclassical and religious scenes. In the 1950s, he began painting murals in private homes in Mexico City, which soon led to a number of public commissions. In several of these murals, Cantú explored pre-Columbian themes, absent from his earlier work, a good example of which is Enseñanzas de Quetzalcóatl (Quetzalcóatl’s Teachings), painted for the home of Benito Coquet (1913–1993).

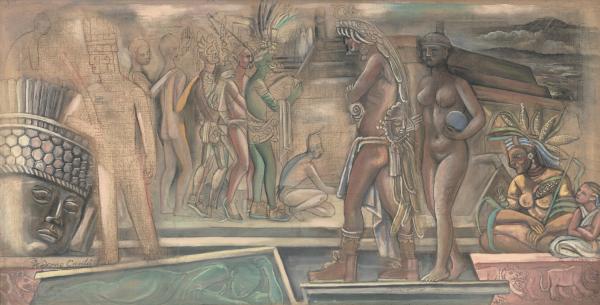

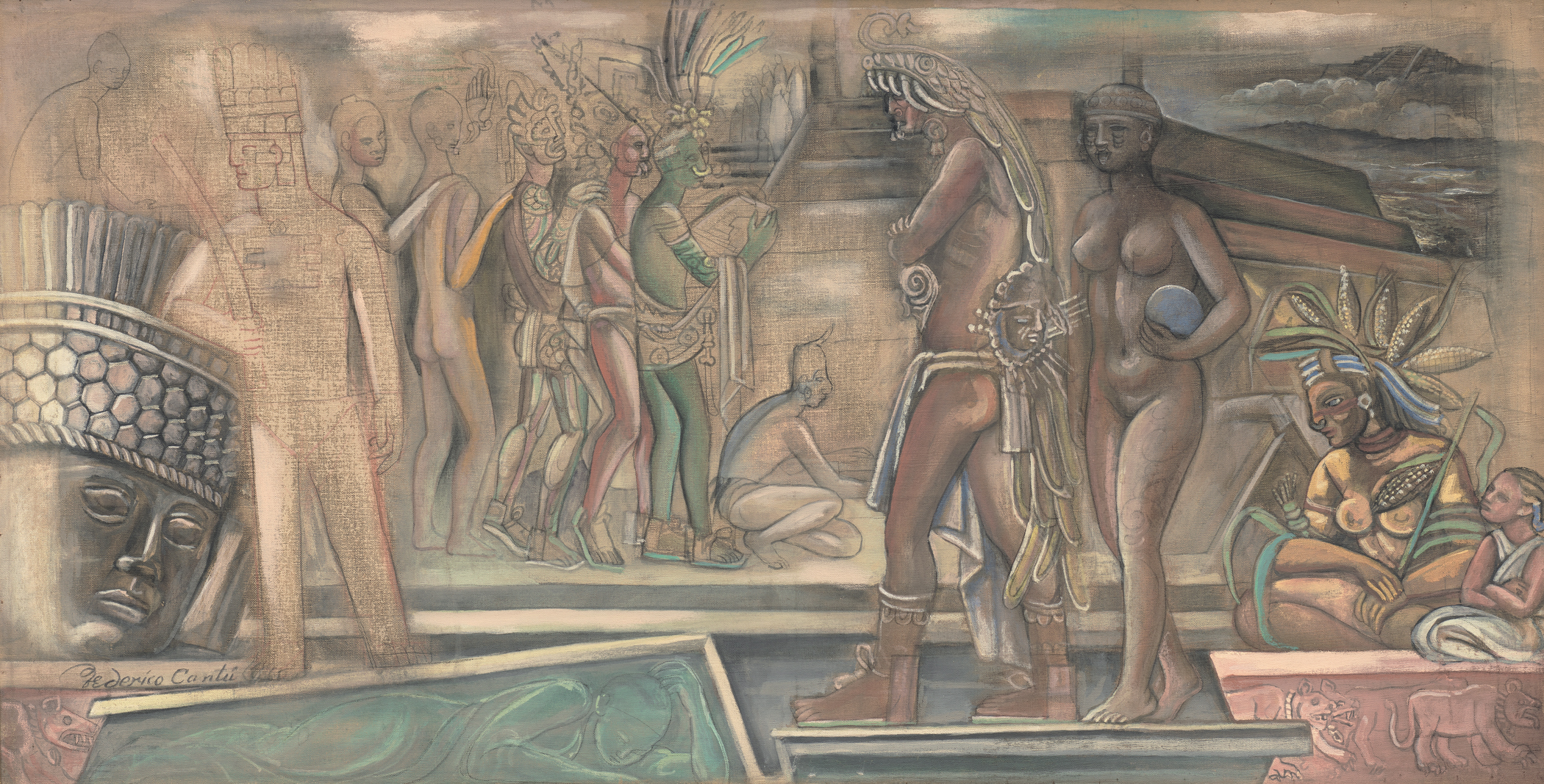

Although the Coquet mural has since been destroyed, Cantú created several variants of the subject, including a large study in LACMA’s collection. This study provides insight into the artist’s interest in ancient Mexican culture as well as his working process. LACMA’s painting is over two feet tall and almost five feet long. It dates to 1960, when Cantú was working on the subject in various media for the Mexican Social Security Institute, known as IMSS, then directed by Coquet.

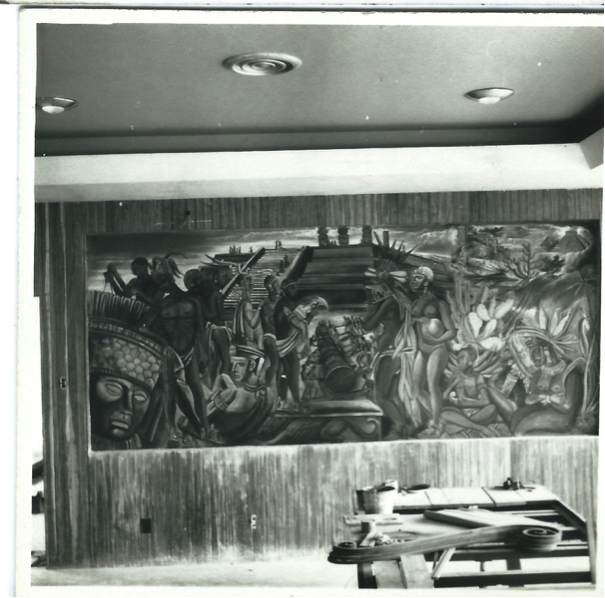

The IMSS built a number of housing developments and hospitals, commissioning murals as part of the agency’s broader interest in the visual and performing arts and as an extension of the legacy of the Mexican mural movement that began in the 1920s. While the revolutionary potential of murals in Mexico may have reached a peak in the 1920s and 1930s, these later projects demonstrated an ongoing interest in muralism in private and public sectors. Elements from both the LACMA canvas and Coquet mural are present in three of Cantú’s IMSS commissions, as well as a large copper engraving at the Autonomous University in the artist’s home state of Nuevo León.

These works depict moments from the reign of Quetzalcóatl, the plumed serpent god in his human incarnation. The scene is set at the archaeological site of Tula, northwest of Mexico City, believed to be the capital of the Toltec civilization. The Toltecs were widely recognized for the skill of their warriors and the contributions of their artisans. Beginning in 1940, the archaeologist Jorge Acosta (1904?–1975) led a series of excavations in Tula. One of his goals was to restore the site and its great pyramid, the main structure visible in Cantú’s work. Acosta’s archaeological discoveries spurred interest in imagery from Tula. For instance, a colossal warrior sculpture found on the pyramid welcomed visitors to the Mexican Pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair; and, in 1964, Alfredo Zalce (1908–2003) depicted Tula's construction as part of the didactic mural program for Mexico’s National Museum of Anthropology. Like Cantú’s murals, these projects referenced Tula as an example of Mexico’s grand past.

In Cantú’s Tula, Quetzalcóatl looms large in the foreground. To his right, the goddess Coyolxauhqui carries the moon while the goddess Xilonen, wearing a corn headdress, sits on a jaguar frieze similar to those excavated at the site. On the left we see the gargantuan stone head of an atlantid, the warrior sculptures believed to have supported a temple roof on the pyramid. Next to the sculpture, a simply rendered figure bears the same circular headdress, butterfly-shaped breastplate, and curved weapon that appear on the complete atlantid columns. His sketched outline, along with other faintly drawn figures and elements, may suggest that Cantú left the piece unfinished. In the center of the painting, a group of colorful and elaborately adorned men approaches the pyramid.

The lead figure in green holds a sketch suggestive of the pyramid before him, perhaps identifying this figure as an architect. In a 1962 stone relief outside an IMSS hospital, also titled Enseñanzas de Quetzalcóatl, Cantú dramatically changed the composition, yet he kept this grouping of figures largely intact. There, instead of holding an architectural sketch, the lead figure carries a ceramic vessel, with paintbrushes slipped into his belt.

In all of his Tula compositions, Cantú places Mexico’s artistic heritage alongside the presence of gods, which is in keeping with other works by the artist that comment on the elevated status of the arts. LACMA’s richly rendered study along with Cantú’s related monumental works exemplify a renewed interest in pre-Columbian art, at a time when the legacy of the mural movement in Mexico was under debate and many artists were searching for alternative means of expression.