Starting later this week, visitors to Picasso and Rivera: Conversations Across Time will have the chance to see Diego Rivera’s Zapatista Landscape (Paisaje Zapatista). The painting comes to us from Mexico’s Museo Nacional de Arte via Paris, where it was recently included in an exhibition at the Grand Palais. Created in the summer of 1915, this masterpiece from Rivera’s time in Paris is an important episode in the histories of Cubism and Mexican Modernism alike.

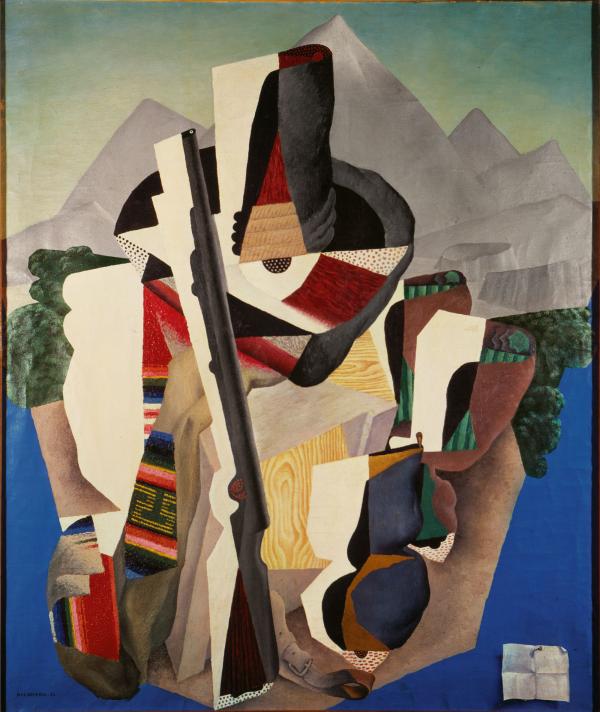

Rivera (1886–1957) first visited Paris in 1909. He returned two years later and settled in the neighborhood of Montparnasse, a hub of artistic activity. There, he began painting Cubist works in 1913; Zapatista Landscape showcases his engagement with this movement. A still life of various objects, shown simultaneously from multiple points of view, dominates the composition. The white shapes around the objects represent the voids left after the objects or vantage points have shifted. Areas of painted wood grain—a technique borrowed from house painters and introduced into Cubist painting by Georges Braque (1882–1963) and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973)—and the careful depiction of a piece of paper nailed to the canvas, introduce realistic details into the painting while Rivera pushes forward into abstract modes of representation. A photograph of Rivera in his studio captures the artist standing proudly in front of this canvas, paint brush and palette in hand.

Zapatista Landscape introduces these still-life elements into a landscape setting, blending the two genres. The background includes snow-capped mountains and volcanoes, distinctive of the Valley of Mexico and drawn from Rivera’s memories of his homeland. The artist references a rich history of portraying Mexico’s terrain, led by the nineteenth-century master José María Velasco (1840–1912) and the radical Gerardo Murillo (1875–1964), better known by the pseudonym Dr. Atl. Within this Cubist painting, Rivera offers a new way of seeing the Mexican landscape.

Rivera also introduces visual connections to Mexico through the painting’s still-life elements. Resting on top of a wooden surface, we see a wide-brimmed felt sombrero with a rope band and the distinctive, colorful stripes of a serape, a woven shawl. The serape’s geometric pattern lent itself well to Cubism, leading Rivera to include the motif in portraits, such as one of his friend, the sculptor Jacques Lipchitz (1891–1973). These symbols introduce references to Mexico’s popular culture and craft production, exuding a sense of Mexican identity from the expatriate artist.

Rivera painted this canvas in Paris during the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920), a long and bloody conflict. While the title Zapatista Landscape did not appear in connection to the work until decades later, it has lent a revolutionary reading to the work. The title references Emiliano Zapata (1879–1919), a celebrated leader of peasant guerrilla forces, and his followers. Zapata often appeared in imagery with his sombrero and gun, both featuring prominently in this painting. In the decades following the Revolution, a new national art emerged that celebrated Mexico’s indigenous past as well as contemporary heroes such as Zapata. Portraits of Zapata appear in Rivera’s murals and prints of the 1920s and 1930s as well as in the work of his peers, such as members of the Taller de Gráfica Popular (The People’s Print Workshop). As the title Zapatista Landscape was not associated with the piece until a later date, we cannot be sure whether Rivera was thinking specifically of Zapata as he painted in 1915, or rather a general peasant type from his homeland. Either way, he purposefully and distinctly introduced visual references to Mexico into this exemplary Cubist canvas.

Rivera returned to Mexico in 1921, where his works increasingly focused on Mexico and its people and Cubist understandings continued to inform his compositions. Don’t miss this incredible opportunity to see Zapatista Landscape here in Los Angeles, where it can be viewed both in the context of Rivera’s Cubist period and his later post-Revolutionary work.