The photographs of James Welling have explored, since his start among the “Pictures Generation” of the 1970s, the technical reaches of the medium to create images addressing both abstraction and representation. Through his experimentations with Polaroids, photograms, black-and-white and color photography, and digital technology, he has worked with subject matter as varied as the poetry of Susan Howe, Andrew Wyeth’s paintings, architecture, and contemporary dance.

For Artists on Art, LACMA’s online video series featuring contemporary artists speaking on objects of their choice from our permanent collection, Welling selected two photographs by László Moholy-Nagy. Today, he speaks more about his connection to these works.

How long have you been thinking about László Moholy-Nagy's photography?

For me, these pictures go back to my thinking about photography in the ’70s. When I discovered Moholy’s photography I had just graduated from CalArts.

Why was the work striking to you?

I studied with John Baldessari and looked at a lot of conceptual art. When I began to look at Moholy’s work, it seemed to be from a totally different era. Very different from the conceptual practice that I had been looking at as a student. So it was an exciting, new, unexplored area—at least for me—to rediscover the history of photography. I found these two types of works, the experimental photogram and the downward-looking constructivist picture, very energizing.

What is a photogram, in brief?

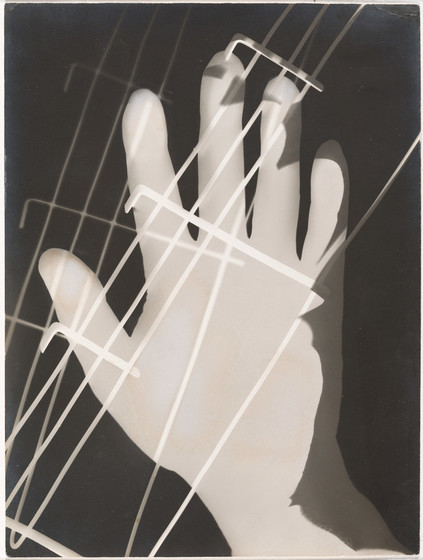

A photogram is a cameraless photograph. A photogram is probably the earliest type of photograph. [Henry] Fox Talbot made cameraless pictures of lace in the 1830s, and even before that [Thomas] Wedgwood, of other objects. The photographer arranges objects on a piece of photographic paper and then makes an exposure. The image that results is a negative and there are shadows. And that’s what the Moholy-Nagy picture shows. It’s a reversed image of his hand that’s shading the photographic paper, so the paper is pure white under his hand. He probably put a metal grid on the paper when he made that first exposure.

How long does a photogram take to make?

Moholy would have probably held his hand for one or two seconds. There is not a lot of movement. You can see the hair on his arms. This is photographic paper, he is controlling the light, he is probably using a bright lamp or an enlarger—so he doesn’t need to have a very long exposure.

Simple enough to explain, but it’s a layered image.

You sort of know what you are going to get, but there are lots of surprises. And I think the surprises in [Moholy’s photogram] are the parts of the photograph that are knocked out or intensified. You have some bright areas in the grid and then you have some darker areas. And it’s unclear what is causing those darker areas in parts of the picture. Possibly another exposure. There is at least a triple exposure in this hand photogram. I’d have to study of it very carefully to figure out. Maybe I want to take a photograph of it and invert it, turn it into a positive. Perhaps there is something else that can be discerned in the picture.

What technical insights can you offer about the aerial photograph of Marseilles?

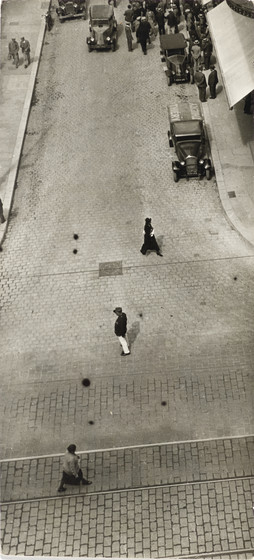

The Marseilles picture, I’d have to look at the negative. I know that some cameras made very long negatives, but my sense is that Moholy has taken a razor blade and trimmed this print. The lower right is a little uneven. Perhaps he has taken an existing vertical negative and made it even more elongated. And that’s a special aspect of this picture, its very elongated shape, which works with the subject, which is a view from halfway into the street and all the way to the bottom, where it meets another street.

And what draws you to it conceptually?

Well, architecture is a parallel current to photography. The Moholy picture of the street . . . it’s not much architecture, but the with idea of the car and the cobblestones and the trolley tracks that are visible, it articulates urban space. I’m interested in buildings and edifices, from H. H. Richardson, who is a proto-modernist, to Philip Johnson and [Ludwig] Mies van der Rohe; and, recently, brutalist architecture, which has a kind of rough surface that I enjoy making pictures of. When I moved to New York [after attending CalArts], I worked at the Museum of Modern Art. I worked in the architecture and design department as a preparator. I was fascinated by all the pictures of architecture that were in their collection.

These are two quite different images. Why did you want to speak about them together?

When I discovered Moholy’s cameraless photograms and then the aerial views looking down, both these classes of image spoke to me about the condition of an enlargement, where the enlarger is projecting an image downward onto a flat easel. So, in the photograms, I imagine that Moholy’s hands are above the photographic paper and light is falling on the paper. Then with this view from Marseilles in the late twenties, Moholy is up high, looking down. And he is mimicking the process of enlarging the print, where the enlarger is typically pointing down. This is something that struck me right away—this sensitivity to the conditions of the photographs being made.

László Moholy-Nagy’s Untitled (variously known as Photogram), 1926, is on view in the exhibition Moholy-Nagy: Future Present in the Art of the Americas Building through June 18, 2017. The conversation was edited and condensed for clarity.