Currently on view in the Resnick Pavilion, Found in Translation: Design in Mexico and California, 1915–1985 displays the beauty in the exchange of visual culture across the border. Throughout the exhibition, we explore the ways in which artists were inspired by indigenous art forms of the past and present. Several works in the exhibition depict the likeness of a particular indigenous figure—Cuauhtémoc, the last Aztec emperor. In honor of Los Angeles's first celebration of Indigenous Peoples Day, this post will look at Cuauhtémoc and his representation over time.

Though short (1520–21), Cuauhtémoc's reign as the final Aztec tlatoani, or leader, helped to seal his name in popular memory. Throughout the Colonial period, Cuauhtémoc was the subject of literary works, though he was rarely represented in pictorial form. Treated as a tragic figure, Cuauhtémoc survived in romanticized retellings of the Spanish Conquest into the late 18th century, his stoicism and bravery in the face of torture and eventual execution on Cortés's command gaining mythical status. In the 19th century, however, as Mexico struggled to define itself following independence (1821) and the American intervention (1846–48), Cuauhtémoc became emblematic of the Mexico of the liberal imagination—he represented an independent Mexico, his suffering and execution under the Spanish recalling the many abuses of the Colonial system itself.

An early monument was erected to Cuauhtémoc on the Paseo de la Viga, Mexico City, in 1869, but unfortunately it no longer survives. Just a few years later, President Porfirio Díaz ordered the construction of a monument to Cuauhtémoc on the Paseo de la Reforma, one of Mexico City's grand boulevards.

The monument represents a significant moment when Cuauhtémoc became a nationalist symbol. It also represents a watershed in design—the base for the monument uses a pastiche of elements from Tula and Mitla, both pre-Hispanic sites of the Mexican Altiplano, and Neo-Classical European architecture, comprising the first grand scale example of Neo-Aztec architecture. The base was designed by Francisco María Jiménez and Ramón Agea while the bronze sculpture of Cuauhtémoc, which draws heavily from Greco-Roman statuary, was executed by Manuel Noreña. In true Neo-Classical style, Cuauhtémoc's idealized body was meant to reflect his character—his stoic expression belies the destruction and horror of the Conquest.

A smaller reproduction of the statue, commissioned by the newly formed brewery Cervecería Cuauhtémoc, was sent to the World's Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893. Later, in 1922, a bronze replica of the statue traveled to Rio de Janeiro for the Universal Exposition to represent the shared ancient indigenous history between Mexico and Brazil. In this instance, the figure moved beyond a nationalist purpose and adopted a universalist one—rather than just representing Mexico's struggle against Spanish imperialism, it embodied the shared struggle of formerly colonized Latin American countries.

At the same time, artists from diverse disciplines experienced a burgeoning interest in the artistic traditions of Mexico's indigenous communities. Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo most famously incorporated indigenous figures and themes in their work. They were joined by artists including Roberto Montenegro, whose 1922 depiction of Cuauhtémoc represents both the emperor and his namesake—Cuauhtémoc can mean descending eagle.

Though Diego Rivera depicted Cuauhtémoc in a mural of Mexico's history at the Palacio Nacional (completed 1930), the historical figure received less individual attention early in the mural movement. By mid-century, muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros worked extensively with Cuauhtémoc's image. According to Christopher Fulton, who has written extensively on Cuauhtémoc, Siqueiros was the first to portray Cuauhtémoc as an empowered indigenous actor.

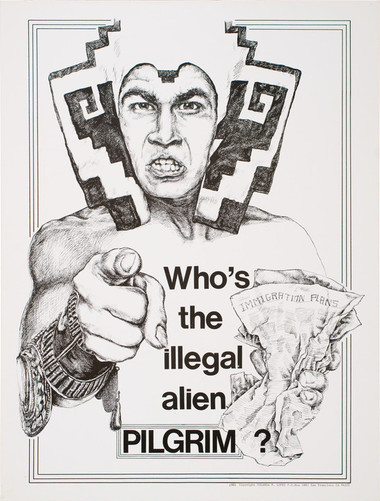

In the second half of the 20th century, the spirit of indigenismo spread throughout Mexico, seeking to empower indigenous communities by recognizing their contributions to the formation of the Mexican state and encouraging their autonomy. The spirit of indigenismo was adopted within the Chicano movement of the 1960s as well. Reclaiming their indigenous heritage, in part as a rebuke of Colonial de-indigenization, Chicana/o artists envisioned their own form of nationalism centered on Aztlán, the mythical homeland of the Aztecs. Though none of the Chicano art featured in the exhibition depicts Cuauhtémoc specifically, posters by Judithe Hernández and Yolanda López both incorporate Aztec warriors. López's poster, in particular, uses the figure to evoke the particular Chicano experience of having an identity rooted both in American imperialism and Spanish colonialism.

Through a versatile display of objects, Found in Translation offers a wealth of stories of cultural interchange. Visit the exhibition to learn more about Cuauhtémoc and the important links between Mexico and California over time.

Found in Translation is on view in the Resnick Pavilion through April 1, 2018.