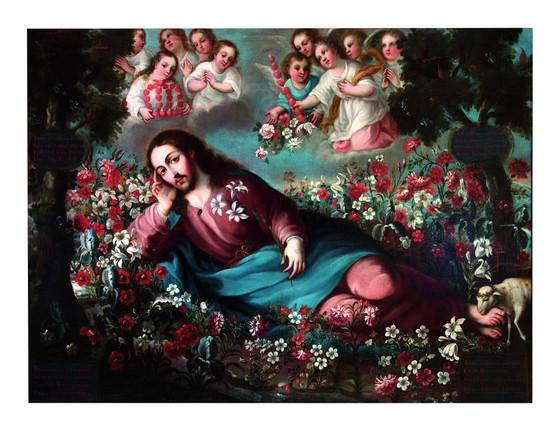

With less than one week before Painted in Mexico: 1700–1790: Pinxit Mexici closes, it is worth considering why so many paintings include hearts. One of the most popular works in the exhibition is Miguel Cabrera’s (c. 1715–1768) The Divine Spouse. This highly imaginative picture depicts a reclining Christ gazing longingly at the viewer; he is surrounded by flowers peppered with words alluding to the virtues required to reach heaven (e.g. purity, chastity, mortification, and love). The Odalisque-like Christ is prone to receive a crown and scepter made of tiny hearts from the cohort of white-clad souls. A lamb, symbolic of his flock, lovingly licks the wounds on his feet, while miniature symbols of the Passion hidden among the flowers refer to his suffering (e.g., the veil of Veronica, nails, and ladder). This kind of image was displayed in a convent to inspire Christ’s brides to imitate his penance and unite with him in eternal love.

_600px.jpg)

Even more explicit is an earlier painting by Juan Rodríguez Juárez (1675–1728) that shows Christ as the Good Shepherd, with the hearts of the nuns piled up in a baptismal font, waiting to be kindled by their divine savior.

One of Cabrera’s most striking paintings, created two years before his death in 1768, exemplifies his close affiliation with the Jesuits—the main promoters of the cult to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. It shows the dying Jesuit Roman novitiate Nicholas Celestini being cured by Saint Aloysius Gonzaga (1568–1591), the famed Jesuit novice known for his thaumaturgic abilities. After Celestini was healed, he vowed to promote the Sacred Heart of Jesus, depicted here as a radiating organ, surrounded by a crown of thorns and surmounted by a cross. The story is reinforced through the unfurled speech scrolls that the figures emit—a textual device that had a long tradition in European art and was commonly employed in 18th-century New Spanish painting to reinforce messages.

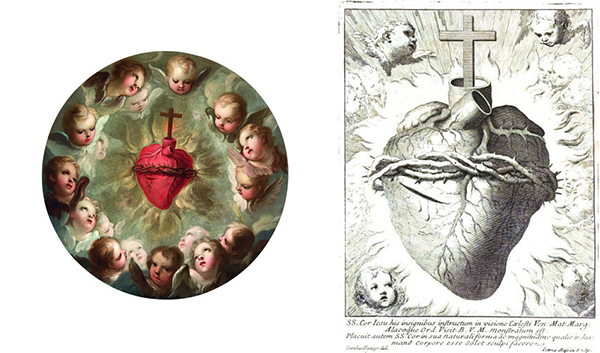

Although devotion to the Sacred Heart originated in medieval times, it was especially promoted by the Jesuits in the 17th and 18th centuries following the visions of the French nun Marguerite Marie Alacoque of 1673–75, who described how Christ offered his wounded heart to her encircled by a crown of thorns and crowned by a cross as proof of his love for humankind, and asked that it be venerated in images. She also associated the heart with the Eucharist. Artists in Mexico created many versions of the subject drawing on Alacoque’s miraculous visions, including Cabrera’s picture of Celestini above, and this small oil on copper of the carnal organ with a ring of cherubs, which refers to a well-known print.

The painted altarpiece above (created to decorate a religious establishment during a special festivity), includes two hearts at the bottom near the inscription specifying that it was commissioned by Mexico’s Archbishop Manuel José Rubio y Salinas (r. 1749–65), confirming the prelate’s interest in propagating the popular devotion.

Like Cabrera, Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz (1713–1772) seems to have made a specialty of the subject. This small oil-on-copper painting portrays a panoply of saints surrounding the Crucifixion with Jesuit founders in the foreground, while the Sacred Heart of Jesus (conflated with the Eucharistic host) hovers on the left—an apt way to proclaim that the heart stood for both the body and soul of Christ.

Despite the popularity of the devotion, it only attained papal support under Clement XIII (r. 1758–69) in 1765. Yet the cult came under increasing scrutiny, in part because of its connection to the Jesuits and the concerted effort of rulers in Spain, Portugal, and France to suppress the order due to its enormous wealth and power.

Enlightened religious reformers also attacked the new cult for what they viewed as mystical excess, its emphasis on a corporeal organ and potentially heretic nature, as they advocated a more simplified and individualized religiosity.

After the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767, King Charles III even attempted to banish all Sacred Heart imagery from his domains, but images persisted and acquired even more political overtones. Some drew inspiration from a painting by the Italian artist Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787) at the Roman church of Il Gesù, showing Christ proffering his own heart. Batoni’s image was created during the height of opposition to the cult and the Society of Jesus. The combination of a gentle Christ gazing at the viewer and holding his own carnal heart—both physical and symbolic—proved to be a highly effective way to connect with worshippers, and the icon reverberated globally.

Artists such as Andrés López (1727–1807) created complex variants, such as this painting (based on a printed source) that depicts Christ gesturing at his heart, while a ray of light emanates from the Eucharist held by a personification of the church, illuminating a bible supported by angels; from there it becomes lightning that annihilates the enemies of the faith, including the cult’s detractors (and by extension the Jesuits' enemies).

Far from disappearing, this highly sensuous and deeply personal image of the “kindled” heart persisted well into the 19th century (and beyond), demonstrating the power of images to invoke piety but also to fulfill undeniable political purposes.

To view these images be sure to catch the exhibition before it closes on March 18 and heads out to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it will be on view from April 23 to July 22, 2018!

Further reading:

Ilona Katzew, ed., Painted in Mexico, 1700–1790: Pinxit Mexici, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Mexico City: Fomento Cultural Banamex, A.C.; Munich, London, and New York: DelMonico Books-Prestel, 2017), cat. nos. 16, 36, 100, 102, 108, and 114–115. Available in the LACMA Store

Lauren G. Kilroy-Ewbank, “Holy Organ or Unholy Idol? Forming a History of the Sacred Heart in New Spain,” Colonial Latin American Review 23, no. 3 (2014): 320–59.

Lauren G. Kilroy-Ewbank, “Love Hurts: Depictions of Christ Wounded in Love in Colonial Mexican Convents,” in Visualizing Sensuous Suffering and Affective Pain in Early Modern Europe and the Spanish Americas, ed. Heather Graham and Lauren G. Kilory-Ewbank (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2018), pp. 313–57.

Jon L. Seydl, “Contesting the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Late Eighteenth-Century Rome,” in Roman Bodies: Antiquity to the Eighteenth Century, ed. Andrew Hopkins and Maria Wyke (London: British School at Rome, 2005), pp. 215–27.