Last summer, Art + Technology Lab grant recipient Jen Liu teamed up with graduate students from the Media Design Practices MFA program (MDP) at ArtCenter College of Design to plan and fabricate sculptural components of her project Pink Slime Caesar Shift. Liu's project incorporates genetic engineering and labor activism into a narrative around the production of synthetic meat and the plight of female factory workers in South China. The wearable sculpture she recently worked on involves the transference of genetic messages and biolistics—the delivery of DNA-coated particles. We talked with Jen shortly after she returned from Shanghai where she and her team were working with fabricators.

This is the second installment of our Q&A with Art + Technology Lab grant recipient Jen Liu. Next Monday, January 27, at 4 pm, Liu will be presenting her work at ArtCenter.

Tell us about the wearable sculpture. What was the inspiration behind its design?

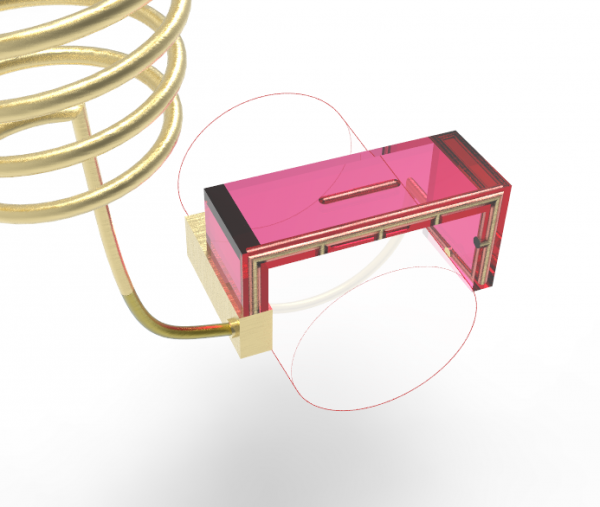

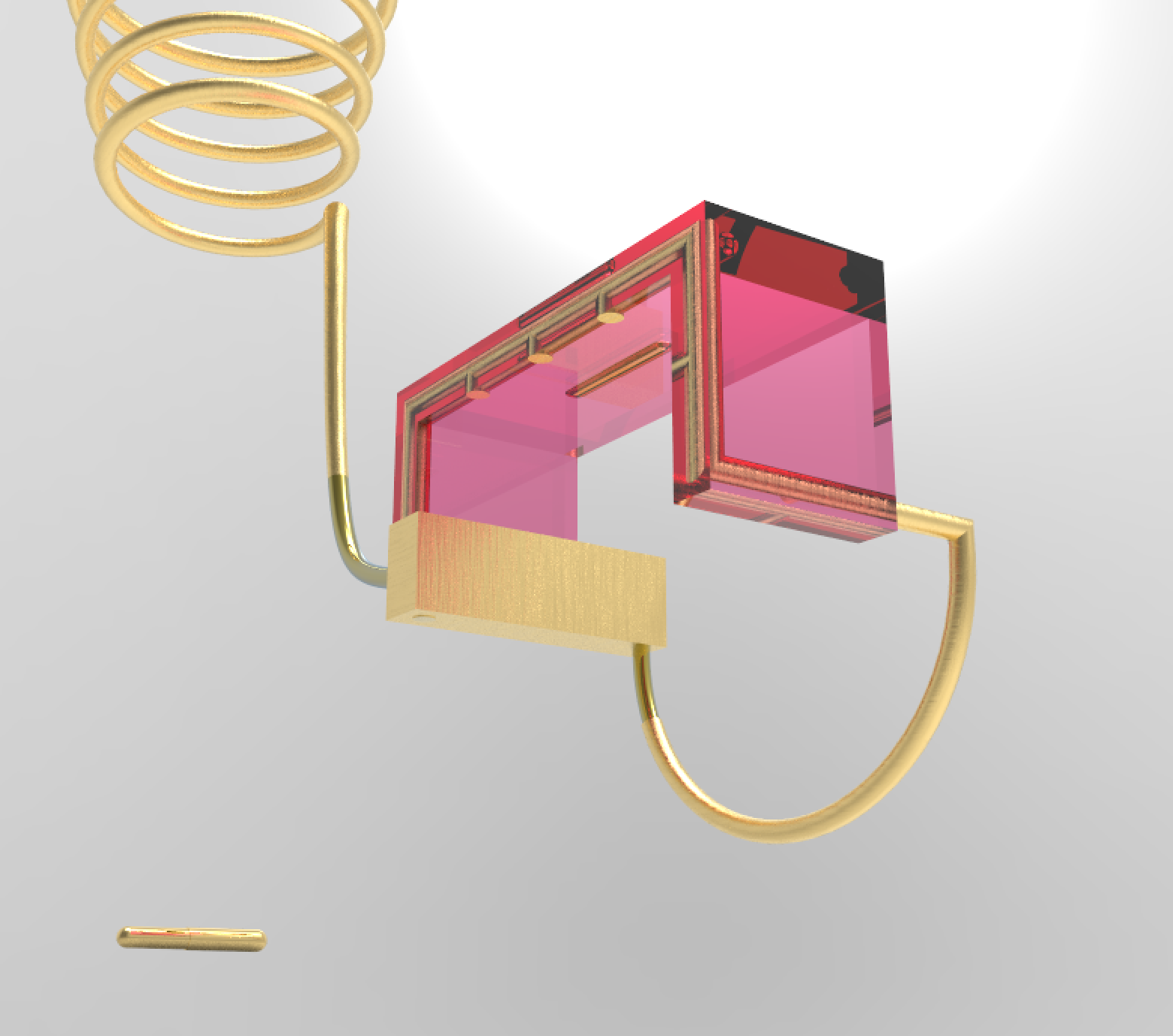

The wearable sculpture—a bracelet—is a functional redesign of an anti-static bracelet, as is worn by electronics factory workers. The bracelets, normally made of aluminum, plastic, and rubber or spandex polyester, electrically ground the workers, so they don't generate static shock, potentially frying the circuits of the products they are assembling. Here, they are made of pink acrylic cast around a gold-plated brass circuit with fine manual mechanisms for customized fit, skin contact points, and a connection port that can be retrofit to work with existing electronic grounding circuit boards, as are currently in use.

.jpg)

When I first saw documentation of a line of workers wearing anti-static bracelets, I assumed they were ergonomic wrist supports, similar to the floating saw wire suspension lines in meat packing plants which reduce the strain of lifting and supporting extremely heavy saws—as well as helping to avoid slip and falls with spinning blades meant to cut through bone, muscle, and gristle. For the electronics workers, if the wrist was supported, then not only would repetitive movement injuries be reduced, but they could also do their work more efficiently—fine gestures with small parts unimpeded by their own bulky wrists and arms. Given this understanding, it seemed ironic that these tethered bands visually spoke so much of incarceration and involuntary labor, worker after worker tethered to the wall above.

_1.png)

However, after further inquiry, it turns out there is no ergonomic function to these bands after all: they serve strictly to protect the product from the workers as anti-static barriers—as well as to monitor the movements of the workers. The electronic docks that the bracelets plug into can be programmed to record whenever the workers step away from their work—unauthorized breaks to the bathroom, to drink water, etc. This information can be used to reduce pay to the bare minimum of working time recorded, down to the second. What seemed like a paradoxical image of ergonomic incarceration became, instead, a simple visual metaphor for its true purposes, protection of the product against and above the worker, and control surveillance.

How does the bracelet design relate to the larger ideas behind Pink Slime Caesar Shift?

The visual excess of the bracelets are a tribute to the glamour of many of these factory workers, femme fabulousness embraced despite a limited range of social and geographical contact. Many in the West have a skewed version of what workers look like today, maintaining the mutual exclusivity of large-scale labor exploitation with first world aesthetics and gendered consumption—which parallels the false mutual exclusivity of intimate capital impacts and cultural consequence between West and East. These bracelets are no more beautiful than these women themselves, and no more "produced." However, this beauty is an ambivalent production: as with everything in Pink Slime Caesar Shift, the principle of toxic femininity, pink tax, overproduction, and the excess of capital expenditure as the cornerstone of gendered precarity—are in full swing.

How else is this notion of “excess” explored in your project?

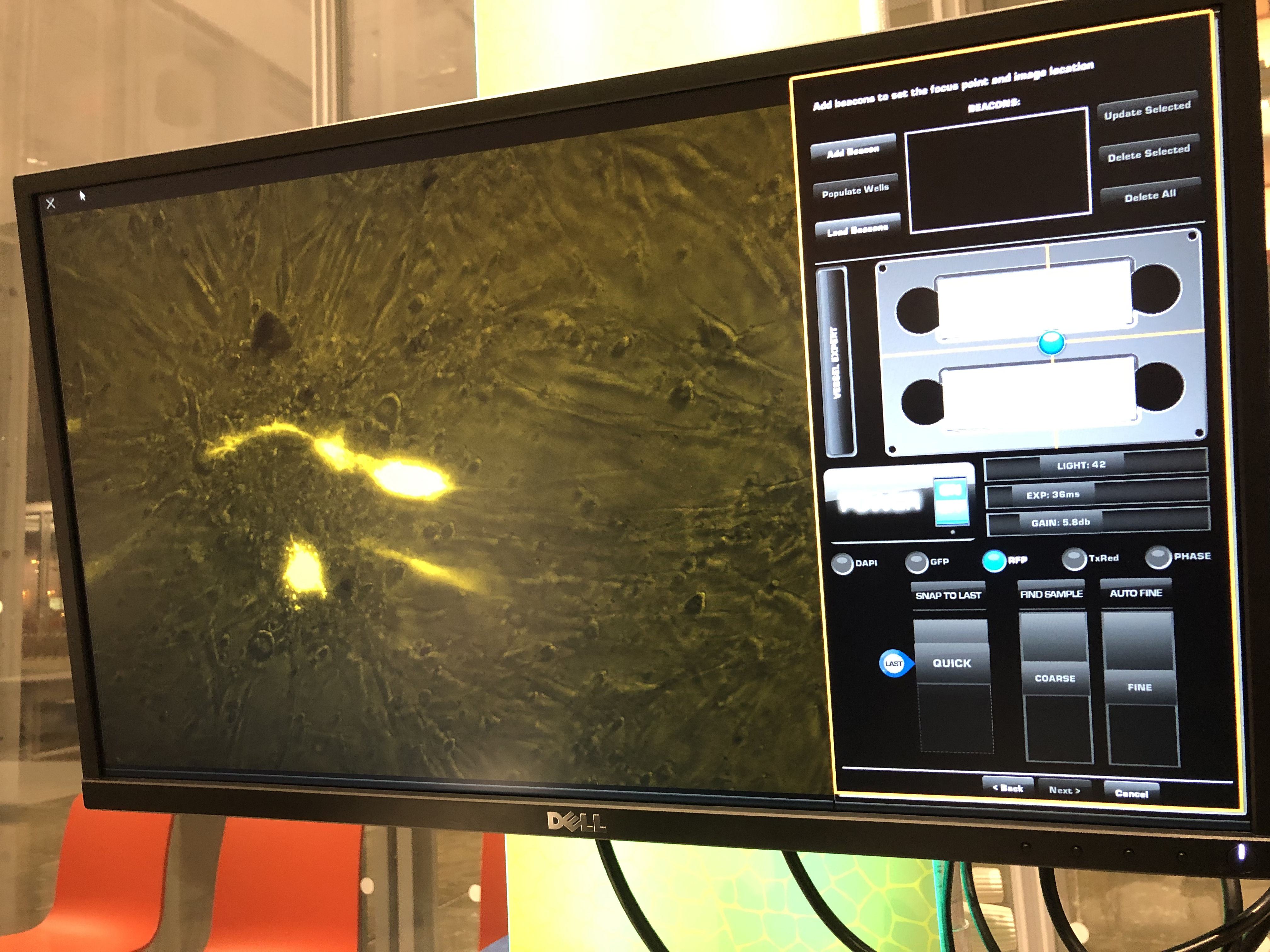

There are two other ways in which excess is exemplified in the bracelet. First, in accordance with the greater narrative of Pink Slime Caesar Shift, these objects contain data-holding modified genetic material that could be propagated in the present and near future—data of particular interest to labor activists in South China—distributed through alternative distribution networks (food vs social). These bracelets each have a gold-plated brass capsule embedded in the acrylic, separated from the static circuit (thus inert). Inside each capsule is a small roll of lab blotting paper, to which are clinging genetically modified cow muscular cells—Proposal #3: Gold Biolistics of Pink Slime Caesar Shift. Together with biologist Sumeyye Yar, I assembled a string of synthetic DNA in two parts: the first part initiates the production of a yellow fluorescent protein, which makes the cell glow yellow under a fluorescent microscope, followed by a second part—a lightly encrypted text which lists 40 historically proofed methods of non-violent protest from the Einstein Institute. The method of its encryption can easily be decoded by anyone with a working knowledge of DNA: amino acid codon triplets all have international standard abbreviations, which strung together, can constitute a text—in this case, a pinyin translation of protest methods for activist education. This synthetic material was successfully introduced into the muscular cells through a gold biolistics gun (lab proof: glowing), and while the cells are dead by now, their genetic material is ready to be identified and propagated into in-vitro beef cells (or any living cells, for that matter!) should the need arise at any point—they simply need to be broken out of the bracelet casing.

Second, the bracelet is itself a discursive object: how do we know the state of labor today, aside from images of spectacular exploitation, operatic images of poverty and suffering? Or can we also know it through its many traces—humble, quotidian objects, factual but also lyrical? Revisionism is excessive—this bracelet is not the simple band and coil object of the original. Yet revisionism expands exposure of the original—its excess tethering it to geographies and spheres of discourse outside its native context—which is the logic at the heart of Pink Slime Caesar Shift.

The Art + Technology Lab is presented by

The Art + Technology Lab is made possible by Accenture and Snap Inc.

Additional support is provided by SpaceX and Google.

The Lab is part of The Hyundai Project: Art + Technology at LACMA, a joint initiative exploring the convergence of art and technology.

Seed funding for the development of the Art + Technology Lab was provided by the Los Angeles County Quality and Productivity Commission through the Productivity Investment Fund and LACMA Trustee David Bohnett.