While LACMA is temporarily closed to the public, our mission remains to celebrate centuries of creativity and inspiring human endeavors. We’ve asked various members of the museum’s staff to share which favorite LACMA artworks—from ancient to modern, from East to West, from world-renowned to more obscure—they would love to have in their homes during this time.

François Boucher’s Study of a Cabbage

François Boucher is synonymous with the flamboyant Rococo style and would eventually become painter to the French royal court, but for the drawing Study of a Cabbage he applied his talents to a rather humble object. He portrays the cabbage with a delicate and animated hand and gives this rustic table vegetable the same sort of attention he would have given Madame de Pompadour’s skirt. They’re given equal treatment in the eye of the artist, and you get a real sense of his love of drawing.

Paul Cezanne’s Study of Nudes Diving

This drawing fascinates me. It’s a great rendering of figures, done with a combination of contour line and animated hatch marks. In addition, it demonstrates the particular role of paper as space and potentiality in drawing. When I’m looking at a painting and I see exposed canvas, it often reads as unfinished, but with drawings I don’t sense that. The paper is so much of what drawing is—it doesn’t have to be filled to feel complete. In this case, the paper is lightly coated with gouache, so we know Cézanne wanted it to be read as part of a composition. At the same time, you can see a partial rendering of a face (the eyes and nose) in the upper left-hand corner, pointing to the drawing’s probable origins in a sketchbook, as well as the exploratory nature of drawing.

Interestingly, the figures weren’t diving when Cézanne drew them, nor was photography used. They were lying on the floor of his studio, stretched out with their heads raised. That makes me like the drawing even more, as a glimpse into the artist’s studio practice.

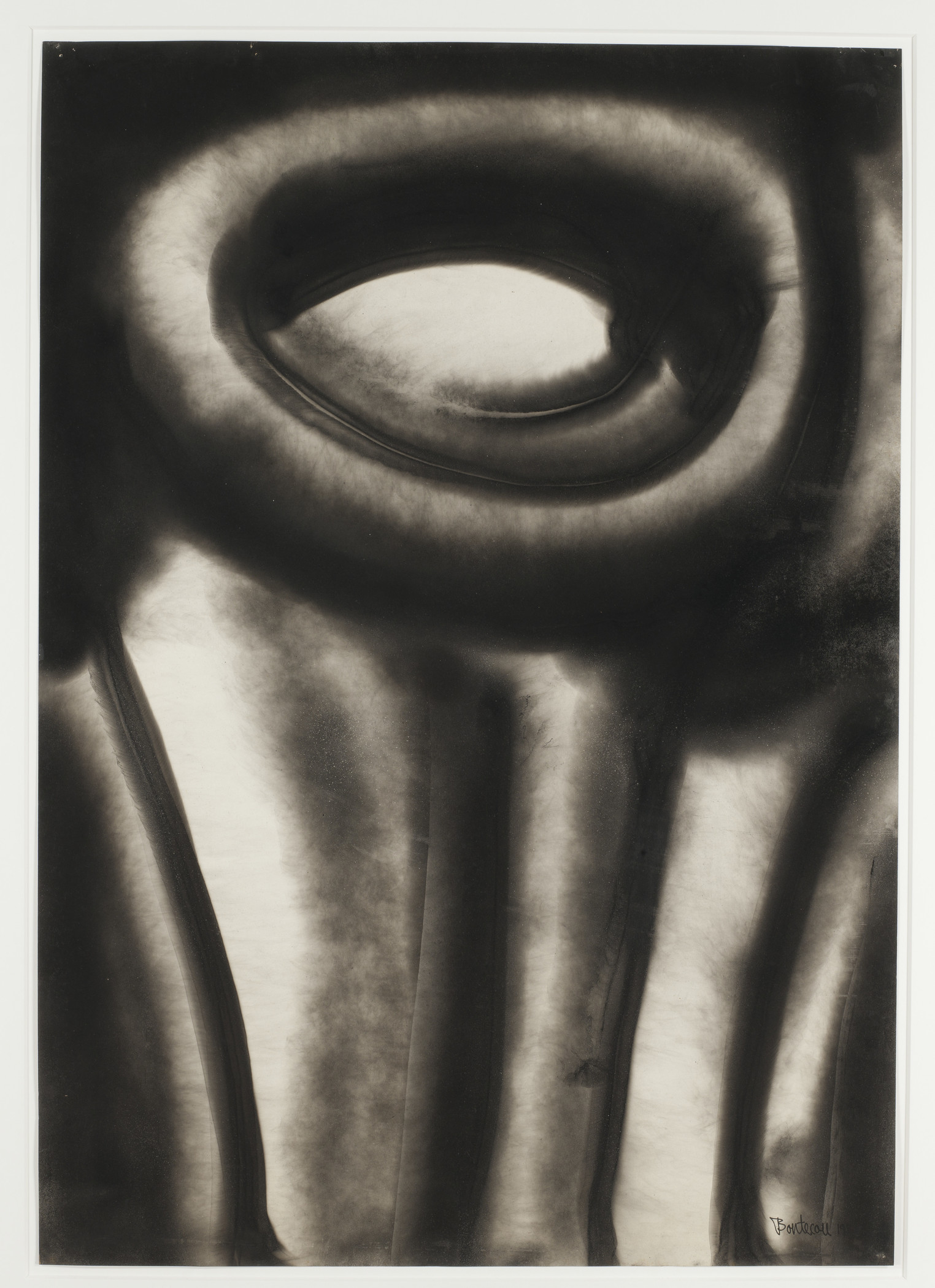

Lee Bontecou’s Untitled

Beginning in the late 1950s, Lee Bontecou created a series of drawings using soot as the medium. She was working with a welding torch, and she realized that if she turned off the flame, the torch would breathe out soot. I love the fact that this takes us back to the origins of drawing—carbon was one of the first drawing media. It also points to the very experimental nature of drawing—you can use anything to make a drawing, even a welding torch.

These observations were first published in the Summer 2017 issue of Drawing Magazine as part of their "Curator's Choice" series.