LACMA's Art of the Ancient Americas department has partnered with the Department of Anthropology at California State University, Dominguez Hills to offer internships to CSUDH students. The program provides an opportunity for students to learn practical curatorial skills and gain hands-on experience in collections-based research while shadowing LACMA staff. Our inaugural cohort of interns began work in LACMA's off-site storage facilities at the beginning of the spring semester, but the program was interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our interns went digital, meeting virtually and researching the permanent collection using LACMA's digital resources. This series of blog posts and StoryMaps showcases what our first cohort of CSUDH-LACMA Anthropology Interns have accomplished. Be sure to read the work of our other interns: Fernanda Hernandez's post for Unframed, "Examining Tlatilco Figurines," Katherine Gendron's StoryMap, "Art of the Ancient Ones," and Yesenia Rubi Landa's StoryMap "The Many Lives of Artifacts."

Imagine this: you are sitting in a public space and your favorite song comes on. You begin to tap along. As you hear the beat, you just cannot seem to keep your body from moving. The sensation you are so desperately fighting is your body telling you it wants to express what it is feeling. Dance moves us, in much the same way that art does.

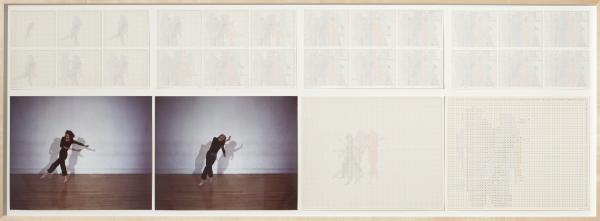

Dance and art have been connected for millennia, something that LACMA’s permanent collection can attest to. Take for example, the piece Trisha Brown Dance, Set 3 by Charles Gaines, pictured above, in which Gaines plots the movements of the legendary postmodern choreographer Trisha Brown, who was known for developing new and interesting shapes in her choreography. In his art, Gaines plotted these shapes in different sequences, allowing the viewer to experience Brown’s dance in a new way.

Art also demonstrates how dance has existed as a form of expression since ancient times. As seen on the shoulder of the Greek red-figure hydria above, dated c. 440 BCE, a warrior dances along to a woman playing the pipes. The image on the ceramic manifests an appreciation of dance: the dancing warrior physically translates the music being played by the woman with the pipes. On the body of the ceramic, two women face a third, who holds a kithara (an instrument with a wooden sound box that has two arms attached to a yoke with strings, an Ancient Greek version of a guitar). The scene reveals the valuable connection between people, music, and dance.

For many communities, dance is an earnest cultural custom that not only captivates people but empowers social connections. This is especially true for the Indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica. One example is the folding screen above, from around the year 1690, which was painted with a scene that took place in a village near Mexico City. The screen, or biombo, depicts a wedding ceremony for an Indigenous couple. Dancers celebrate by performing a mitote (lower right), an Aztec dance, as well as the Danza de los Voladores, the flying pole dance (center).

The folding screen shows how Indigenous traditions began to change under Spanish colonialism, as well as the resilience of Aztec (Nahua) culture. The screen depicts the Indigenous couple leaving a church, which is evidence of their conversion to Christianity. However, the dances displayed on the screen are Indigenous traditions that survived Spanish colonization. The mitote and Danza de los Voladores are pre-Columbian dances that are still performed today. Every year on December 12, Aztec dancers perform in Placita Olvera in downtown Los Angeles to honor the Virgin of Guadalupe, and the flying pole dance is still performed in communities across Mexico and Guatemala. An ancient ceramic model from Nayarit, Mexico (200 BCE–500 CE) depicts a version of this pole ceremony, showing how long this custom has survived.

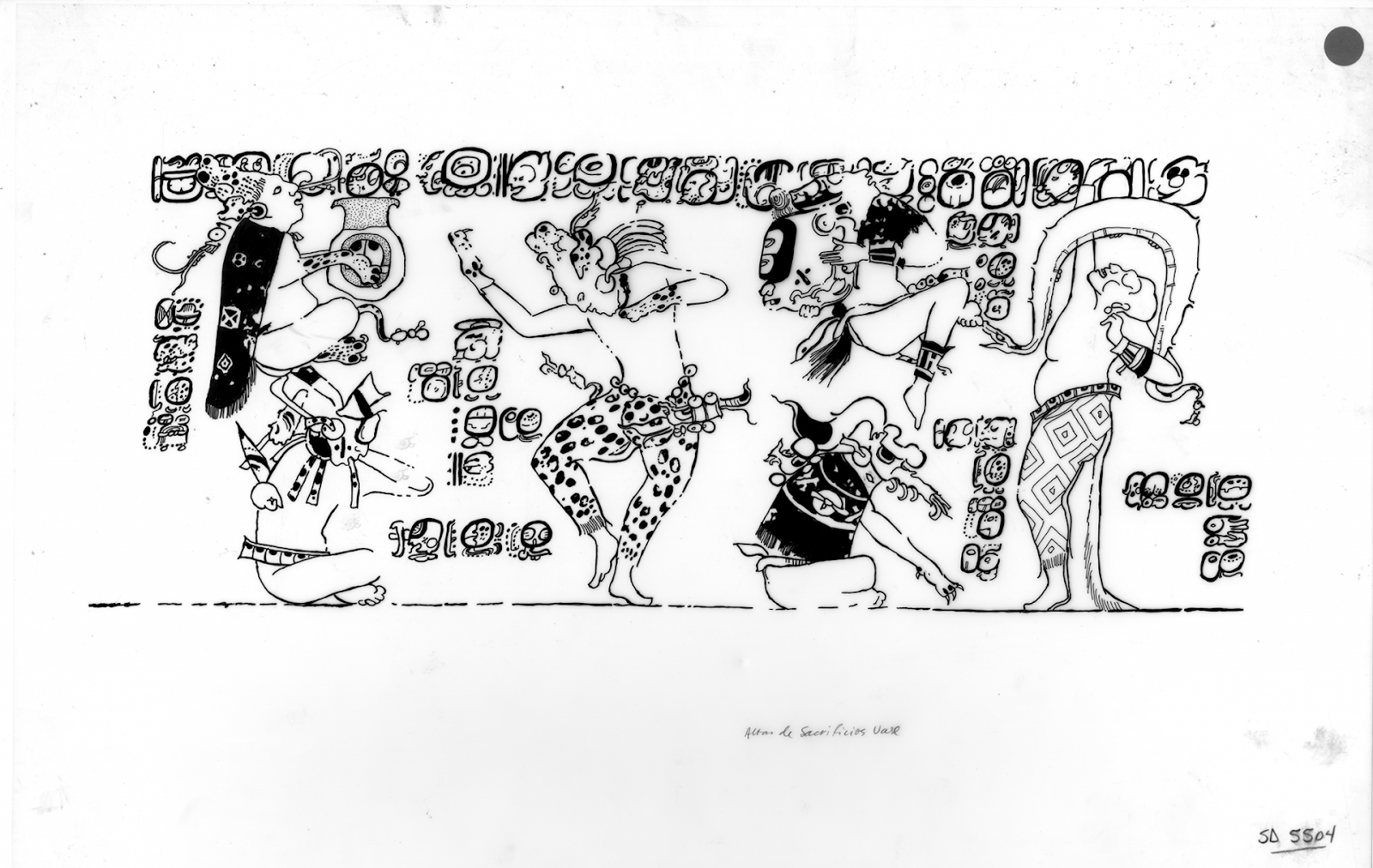

Dances were also among the most important rites performed by ruling elites during the Classic Maya period (c. 250–900 CE), and we can see evidence of those dances depicted on Maya sculpted stone monuments and painted ceramics. One particular dance, known as the "snake dance," is associated with the Maya rain god, Chahk, perhaps as a request for rain. A snake dancer can be seen on a vase from Altar de Sacrificios, Guatemala (far right in the rollout drawing below). Maya peoples used dance to enact their religious beliefs, a practice that continues to this day as versions of the snake dance are still performed in the Guatemalan highlands. Like the Nahua, many traditional Maya dances survived colonization.

Chahk was not the only Maya deity worshipped with dance; a lot of evidence indicates that ancient Maya peoples used dance to worship the maize god as well. A common theme, known as the "Holmul Dancer" motif, which appears on polychrome pottery vessels from the Late Classic period (c. 600–900 CE), depicts a dance associated with the maize god. The theme was first identified on a series of ceramics excavated from the Classic Maya site of Holmul, Guatemala in the early 1910s; however, the motif appears on ceramics and other media throughout the Classic Maya lowlands.

The image of the "Holmul Dancer" can be described as a male dancer bending his knees and reaching out his arms, often accompanied by a dancing dwarf who mirrors his movements. The male dancer is dressed as a young version of the maize god, and his costume includes a large backrack which contains celestial, earthly, and otherworldly imagery representing the whole of the Maya cosmos. Astronomical and agricultural themes are common in Maya dances, representing cycles of rebirth and renewal. For the Maya, dancing expresses these important cosmic beliefs and provides wonderful insight into the long-held religious views of Maya peoples. Some of these dances are still performed today.

Art reveals how dance plays an important role in expressing culture, across time and place. The day for dance to continue the way it was before the COVID-19 pandemic may seem far away, but we still have the ability to dance in our own spaces. I miss the energy of other dancers cheering each other on as we learned routines in crowded studios, and the excitement of audiences watching us on stage, but the sense of community dance gave us will be something I'll cherish forever. So when you feel your body fidgeting to music, just remember the value dance has had through the centuries, and continues to have for us all.

Further Reading

Grube, Nikolai. "Classic Maya Dance." Ancient Mesoamerica, vol. 3, no. 2, 1992, pp. 201–218., doi:10.1017/s095653610000064x.

Kassing, Gayle. History of Dance. Human Kinetics, 2018.

Katzew, Ilona. “‘Remedo de la ya muerta América’: The Construction of Festive Rites in Colonial Mexico.” In Contested Visions in the Spanish Colonial World, edited by Ilona Katzew, 151–75. Exh. cat. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

Reents-Budet, Dorie. "The 'Holmul Dancer' Theme in Maya Art." Sixth Palenque Round Table (1986): 217-222.

Taube, Karl, and Rhonda Taube. "Drama: Mesoamerican Dance and Drama." Encyclopedia of Religion, edited by Lindsay Jones, 2nd ed., vol. 4, Macmillan Reference USA, 2005, pp. 2463-2467. Gale In Context: U.S. History, https://link-gale-com.libproxy.csudh.edu/apps/doc/CX3424500836/GPS?u=csu.... Accessed 28 July 2020.

Źrałka, Jarosław, et al. "In the Path of the Maize God: a Royal Tomb at Nakum, Petén, Guatemala." Antiquity, vol. 85, no. 329, 2011, pp. 890–908., doi:10.1017/s0003598x00068381.