In honor of Black History Month, we are highlighting works by Black and African American artists across various departments of LACMA's permanent collection to celebrate their lives, their legacies, and their often overlooked impact on art history. Today's focus is on works in the Photography department.

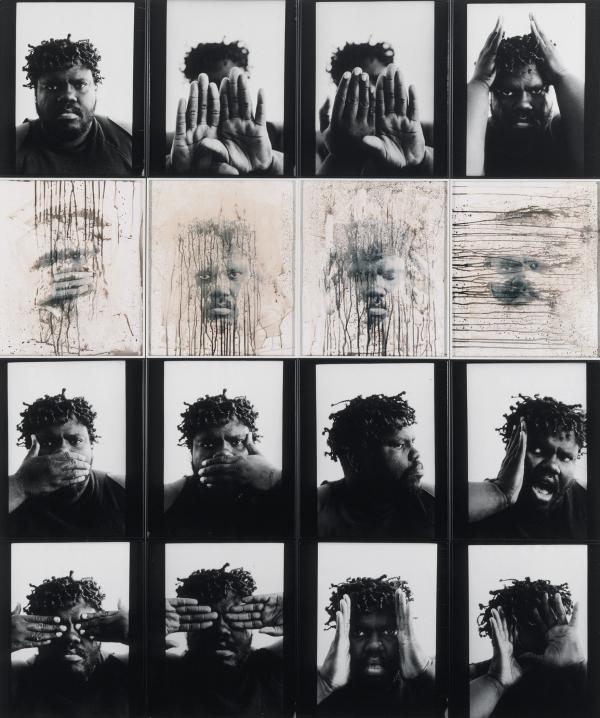

Willie Robert Middlebrook is best known for photographing the African American communities of greater Los Angeles with dignity and respect. This multidimensional self-portrait—on view in the exhibition Golden Hour: California Photography from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art—was Middlebrook's response to the 1992 uprising and to a lifetime of readdressing a Black man's humanity. Alongside this monument-sized work (standing 96 inches high by 80 inches wide), Middlebrook places a short text, written in the manner of an open letter or a journal entry:

As far back as I can remember, my parents would tell us (me and my brothers) that "God created man in his image; that we were created equal; that all people were created equal; that right wins over wrong; be good and good things happen to you."

On April 29 [1992], everything my parents told me went right out the window: We are not equal; right does not win over wrong; God did create man in his own image, as long as you're not black. I came to this conclusion the first time I heard the verdict that was handed down in the [Rodney] King case and from watching and listening to how the media covered the aftermath of the verdicts.

The work In His "Own" Image is a reminder that we are just people. The work is about one man, an African American Male. Through the expressions on his face, the viewer gets to share some of what was felt…what he felt on April 29, 1992, and prior to that.

—Willie Robert Middlebrook, 1992

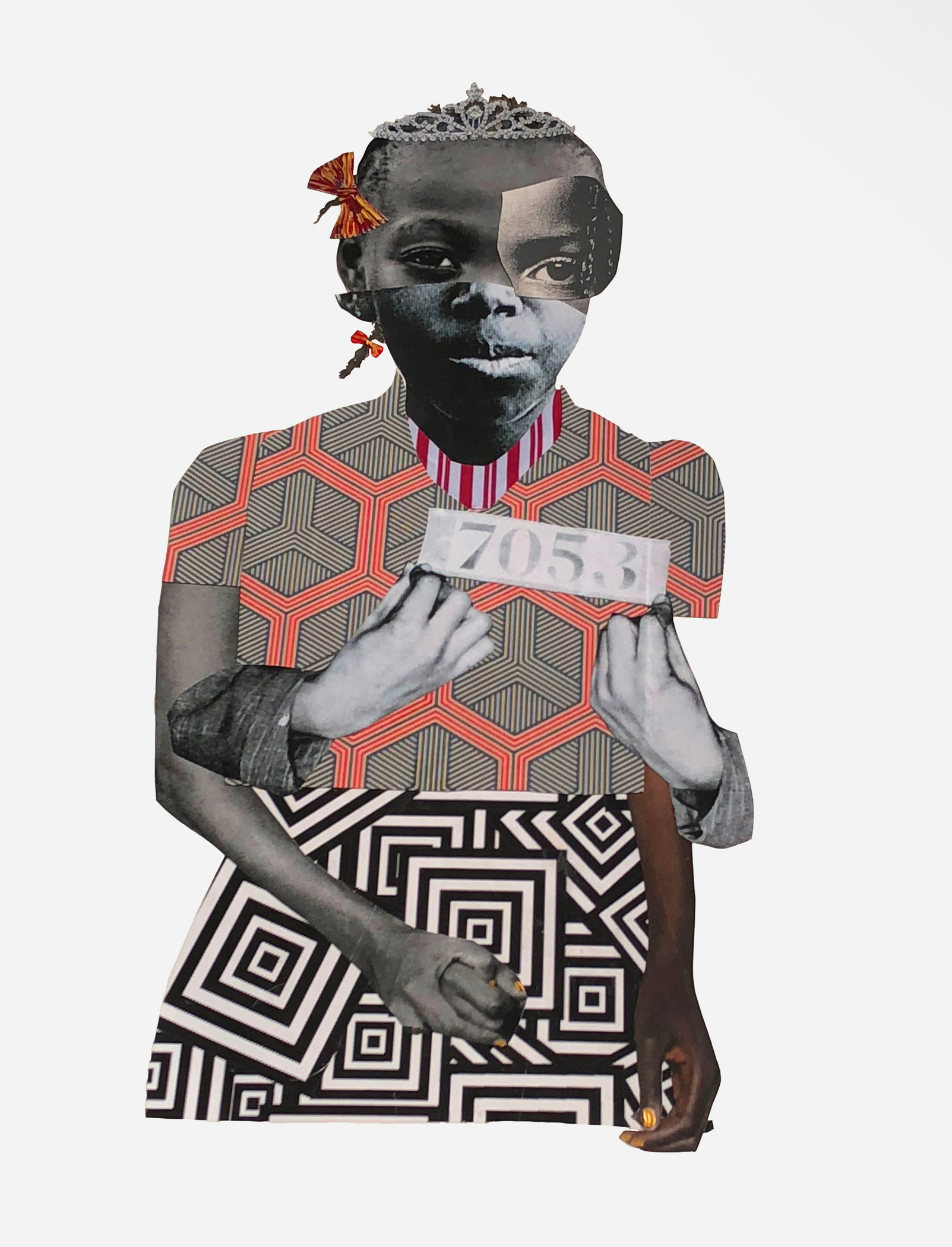

Deborah Roberts uses imagery from magazines and other printed matter that she enlarges, cuts, and crops into collage elements to create representations of Black girls, single or in pairs. In Breaking Ranks, the incongruity of the girl's mismatched limbs evokes preteen awkwardness but also otherworldliness, like some mythic tribal deity. She has four hands, two of which come from Rosa Parks's 1955 mugshot, and two different but large and knowing eyes. Roberts's animated approach to collage is reminiscent of Romare Bearden's but, as pointed out by Los Angeles Times critic Sharon Mizota in a recent review: "Roberts' portraits also feel musical, incorporating bold prints, bright colors and dramatic shifts in scale and perspective, but her eclecticism is much quieter. Her girls appear isolated on white grounds, the center of attention."

The work of artist Paul Mpagi Sepuya uses traditional studio portraiture as a means of examining his own sexuality. He often combines multiple images on a single plane, using mirrors and reflective surfaces, so that disparate scenes of body parts and fabrics collapse into one. In Dark Room Mirror Study (0x5A1525), the artist's hand reaches into the picture plane to press the release button on a camera aimed at a shiny surface marked by a multitude of overlapping fingerprints; emotionally, these are about touch, physical longing, and obfuscation. Intellectually, the viewer builds an understanding of the relationship between artist—who is often included in the image—and male subject.

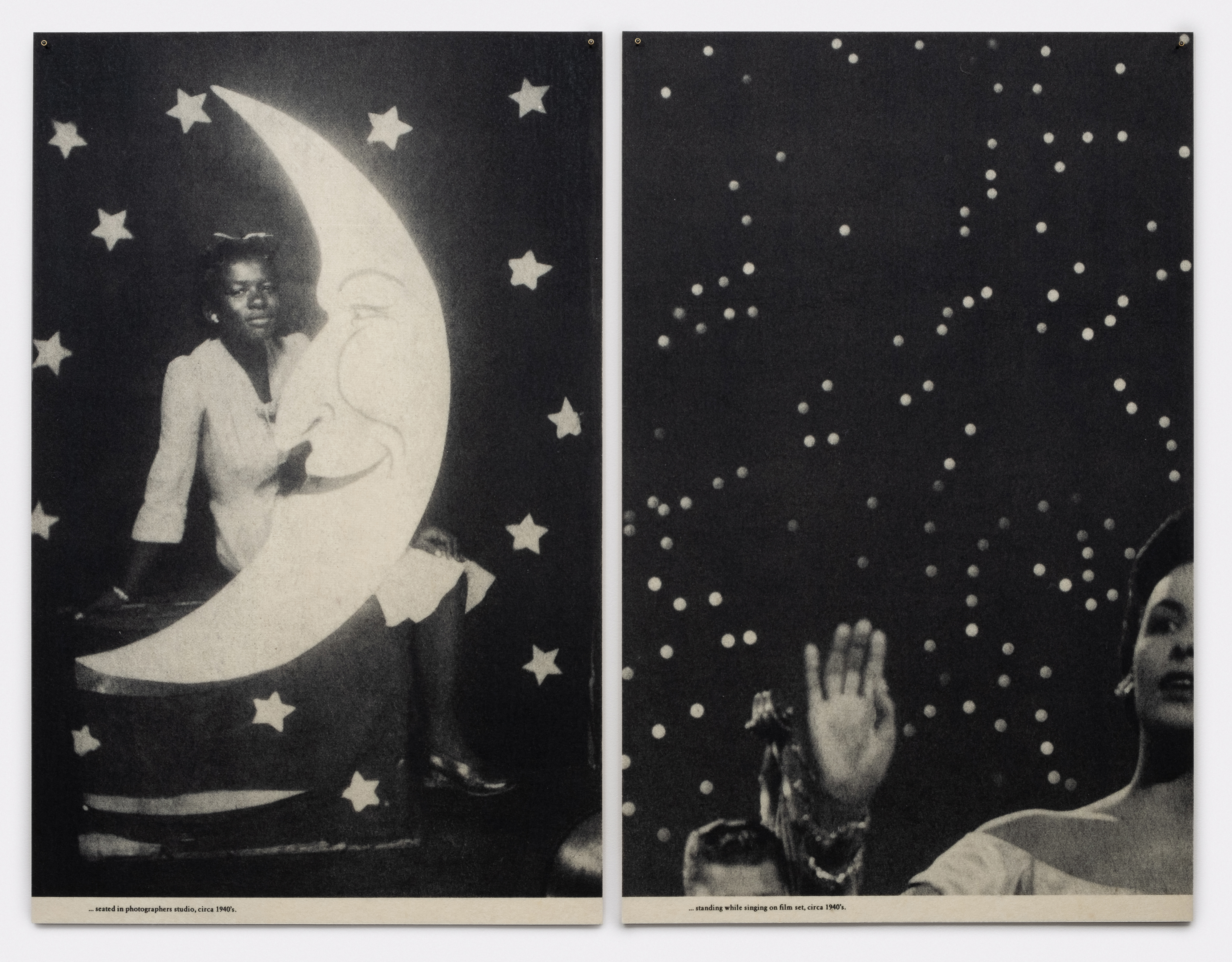

Re-examining photography as a conceptual medium, Lorna Simpson creates multidisciplinary and complex work that raises questions about the nature of representation, identity, gender, race, and history. Often associated with postcolonial and feminist critique, Simpson's work seeks to explicate the ways in which race and gender shape human interactions.

In this diptych, the artist comments on the historical fact that African American women were rarely glamorized in Hollywood productions of the 1940s. We see a fragment of Lena Horne and a full view of an unidentified Black woman, both with equally glamorous backdrops of night skies with stars, both in a photography studio setting so each a manufactured reality. With felt as the photographic support, the blurriness and muted contrasts achieved in the printing render the skin, hair, and dress of the woman on the left as nearly indistinguishable from the contrast of the stage set. On the right, Lena Horne's impact as a singer, dancer, and actress—as well as her role in the civil rights movement—is contrasted by her near invisibility, aligning with Simpson's exploration of the marginalization of Black women in American culture.