Welcome to part 7 of NFTs and the Museum, a series of conversations between art and culture practitioners in and outside of LACMA. The series examines what NFTs mean for museums that collect digital art, and looks at the artistic, curatorial, conservation, registration, and legal issues of this new digital format. For this post, I talked to artist and Art + Technology Lab grant recipient Kyle McDonald, whose new project Amends spotlights historical emissions from three major art NFT marketplaces with the artworks priced to fund the complete carbon mitigation of each.

For the past two years the surging interest in crypto and NFTs has put a spotlight on artists like yourself, who work in the digital space. As your Twitter indicates, you followed this activity closely, focusing primarily on research and critique, but, until now, you haven't claimed a formal position in this dialogue. What motivated you to refrain from participating? What have you learned?

The main change with this project is that I was previously critiquing from the periphery, but this work required me to actually mint NFTs. I don’t plan on minting any more NFTs. From the beginning my goal has been to find a way through this—to find some path that helps see artists to the other side of whatever this may become. I don’t think that NFTs are the right model for supporting digital artists, the same way that I don’t think the contemporary art market is the right model for supporting artists broadly. But I am interested in reflecting on how this ecosystem works and what values are embedded in it.

The main reason I’ve refrained from releasing Amends sooner is that I wanted it to be right. It was conceptually complete over a year ago, but there was a long journey of speaking with all the organizations and experts needed to really make it tight. I’ve also been learning my own direct and indirect connections within crypto and climate spaces. I’ve learned that the same way it’s nearly impossible to escape our environmental impact, it’s becoming difficult to separate ourselves from crypto.

Of course, just because we are connected to harmful systems doesn’t mean we should give in to their harms. But we need to find ways to fight those harms as effectively as possible.

Crypto and NFTs are a complex and often polarizing subject. It's difficult to remain objective or agnostic in this conversation. How have you navigated and maintained relationships in the face of these circumstances?

I’m encouraged by the work of Molly White, a software developer and Wikipedia editor who manages the news site Web3 is going just great, which tracks the rampant failures of the crypto space. On Wikipedia, there is a responsibility to present different perspectives without lending legitimacy to unsupported claims. White does an incredible job of applying this model to her critiques of crypto.

This sounds great in theory but it can get difficult when people feel like a critique of a system is a personal attack on them or their work. I learned this the hard way when some of my early tweets about NFTs were criticized by friends who felt like I was threatening one of the only sources of income they’ve had post-pandemic. Instead of censoring myself, I’ve tried to engage with my friends directly and understand better where they are coming from. Even if I think one “side” is right, I’m more interested in coming to a collective resolution here rather than dividing into warring factions. I also have to admit that anything less than vocal and polarizing rejection may actually be contributing to the social harms of crypto. I don’t know if I’m doing this right, and I often worry that by trying to get everyone to work together I am working against positive change.

There has been critique of carbon offsets as being murky and difficult to validate. How did you come to choose the three carbon mitigation organizations you are working with for Amends?

Carbon offsets have historically been used by major polluters to avoid making reductions, and many offsets don’t do what they claim. They might be sold by some guy who claims he was going to chop down a forest, even if he was never really planning on chopping it down. They might be sold by a corrupt government official who has embezzled most of the revenue and used the leftovers to plant monoculture invasive trees that destroy the local ecosystem. And then that forest will just burn down a few years later.

But there is also an abundance of good and important work happening all over the world. And the only way to get funding for it right now is by selling this work as carbon offsets. The three organizations I partnered with are each taking different approaches.

Nori is a carbon offset marketplace that is currently focused on working with farmers who practice regenerative agriculture. By making key changes to the way that they farm, they can sink carbon dioxide into the soil. This is a benefit for the climate, but it’s also a benefit for the soil, and for our health. Using cover crops and no-till farming keeps microbes in the soil healthy throughout the year, increasing the nutrients available to the plants. These techniques promote resilience, partially by decreasing reliance on inorganic chemical inputs. There is new science here, but the overall approach is ancient and known by many Indigenous peoples.

Project Vesta is researching an experimental process called enhanced coastal weathering. On some beaches around the world there is a green sand called olivine, and when ocean waves crash on these beaches the olivine is chemically converted to bicarbonate, which is used by marine creatures to build their shells and skeletons. This process captures carbon dioxide, and reduces the acidity of the water. It turns out that while only a few beaches have this green sand, olivine is actually the most abundant mineral in the Earth’s upper mantle. Project Vesta is researching whether this natural process can be scaled up to capture a significant portion of historical carbon dioxide emissions, while also de-acidifying the oceans.

Tradewater is dealing with a different kind of historical debt. Old air conditioning systems, like those in old cars, relied on refrigerants like Freon. When these gasses escape into the atmosphere, they cause ten thousand times more warming than carbon dioxide. Even though the worst of these gasses were banned decades ago, the canisters are still sitting in warehouses and garages around the world, slowly rusting through and leaking. Tradewater finds and destroys these canisters before they have the chance to leak. This is absolutely essential work. Even if we traded all the leaking refrigerants for carbon dioxide, there would still be a net gain: carbon dioxide is something we can actually re-capture, but we cannot re-capture refrigerants.

Each of these companies is doing essential work—healing the soil, laying groundwork for the future carbon removal, and managing dangerous gases. Ideally we would be able to fund their work even when we aren’t trying to “offset” emissions elsewhere. This does happen sometimes. For example, Tradewater told me about a tech company that purchases 30x offsets on all their emissions. But we could use a lot more of that.

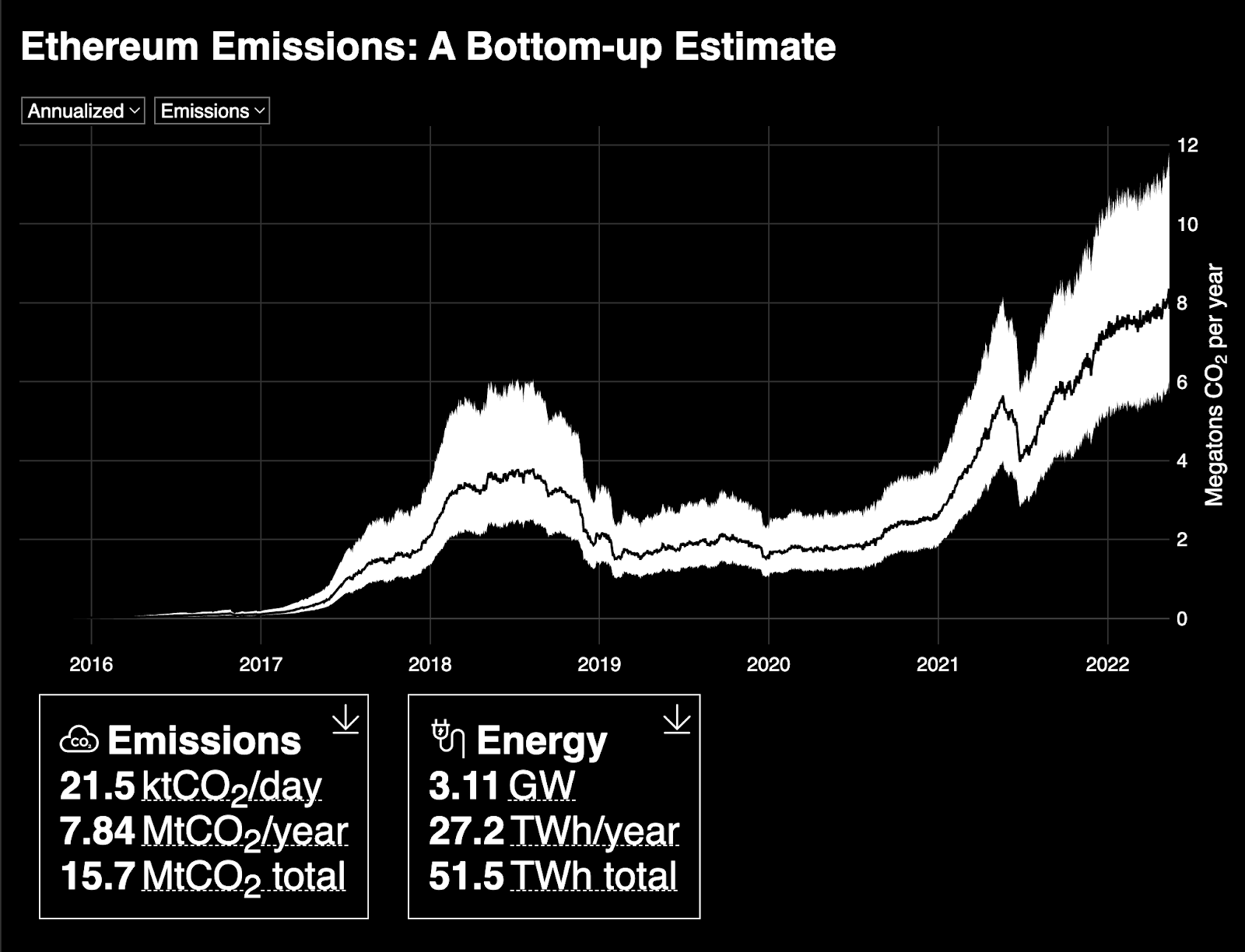

You've put in a lot of time estimating the emissions of the Ethereum blockchain and its marketplaces. Amends focuses on compensating for the CO2 output of three of the largest NFT platforms and quantifies it as a price. Why frame the environmental cost in economic terms?

I want Amends to hold a mirror to the crypto ecosystem. We’ve been told that this moment represents a major change, that we are going to see a decentralization of finance that radically favors individuals over corporate interests—and that this should help solve some of the biggest challenges we face today. And yet the two biggest blockchain ecosystems, Bitcoin and Ethereum, have relied on massively polluting technology that can only create new currency proportional to how much energy it uses (unlike most computational systems, which can be made more energy efficient over time). And they have also seen buy-in from the same venture capitalists who brought us the web infrastructure we use today.

I would like Amends to challenge this narrative by presenting an opportunity for someone to address these historical harms. Because the crypto space operates on a logic of monetary equivalence—everything has a value, and anything can be traded for anything else—I’ve presented these harms within that paradigm.

Perhaps Ethereum will fail before it transitions away from proof-of-work, and the challenge will fall apart before anyone can put in an offer. Perhaps the work will not sell. Perhaps we will see an individual step in who wants to do something, anything, to make things right. In the best case, I’d love to see these companies themselves—Foundation, Rarible, and OpenSea—taking responsibility. But even more than that, I would like to see a future where we have better regulation of corporate reliance on high-emissions systems. I don’t want to cross my fingers and hope that things will be different every time that some new technology gets rolled out.

The Art + Technology Lab is presented by

The Art + Technology Lab is made possible by Snap Inc. Additional support is provided by SpaceX and Google.

The Lab is part of The Hyundai Project: Art + Technology at LACMA, a joint initiative exploring the convergence of art and technology.

Seed funding for the development of the Art + Technology Lab was provided by the Los Angeles County Quality and Productivity Commission through the Productivity Investment Fund and LACMA Trustee David Bohnett.