The visual elements of this tapestry in LACMA’s collection, currently on view in The World Made Wondrous: The Dutch Collector’s Cabinet and the Politics of Possession, can have a dizzying effect. Woven at the turn of the 16th century for an elite patron, the composition is grounded by a dense field of flowers—an example of the maximalist millefleurs (“thousand flowers”) style that flourished in French and Flemish tapestry design during this period. A riot of colors clutters the surface, materialized through sumptuously dyed threads that convey a sense of their original vibrancy despite centuries of wear. From the tapestry’s center unfurl the peach-colored leaves of an acanthus. Their dynamically curled tips embrace and direct attention to the tapestry’s figures: a hairy woman and man with white complexions surmounted by the winged bust of a man with darker skin.

These figures may perplex modern viewers, but they would have also signified a complex range of meanings for Europeans of the late Middle Ages. At their simplest, the woman and man represent the folkloric Wild Man and Wild Woman, while the darker-skinned man represents a “Moor,” a derogatory term Europeans used to reference Muslims from varying regions. Wild Folk and the “Moor’s head” were common tropes in European heraldic imagery. Wild Folk often bore a patron’s coat-of-arms, and the Moor’s head was frequently integrated into family crests.

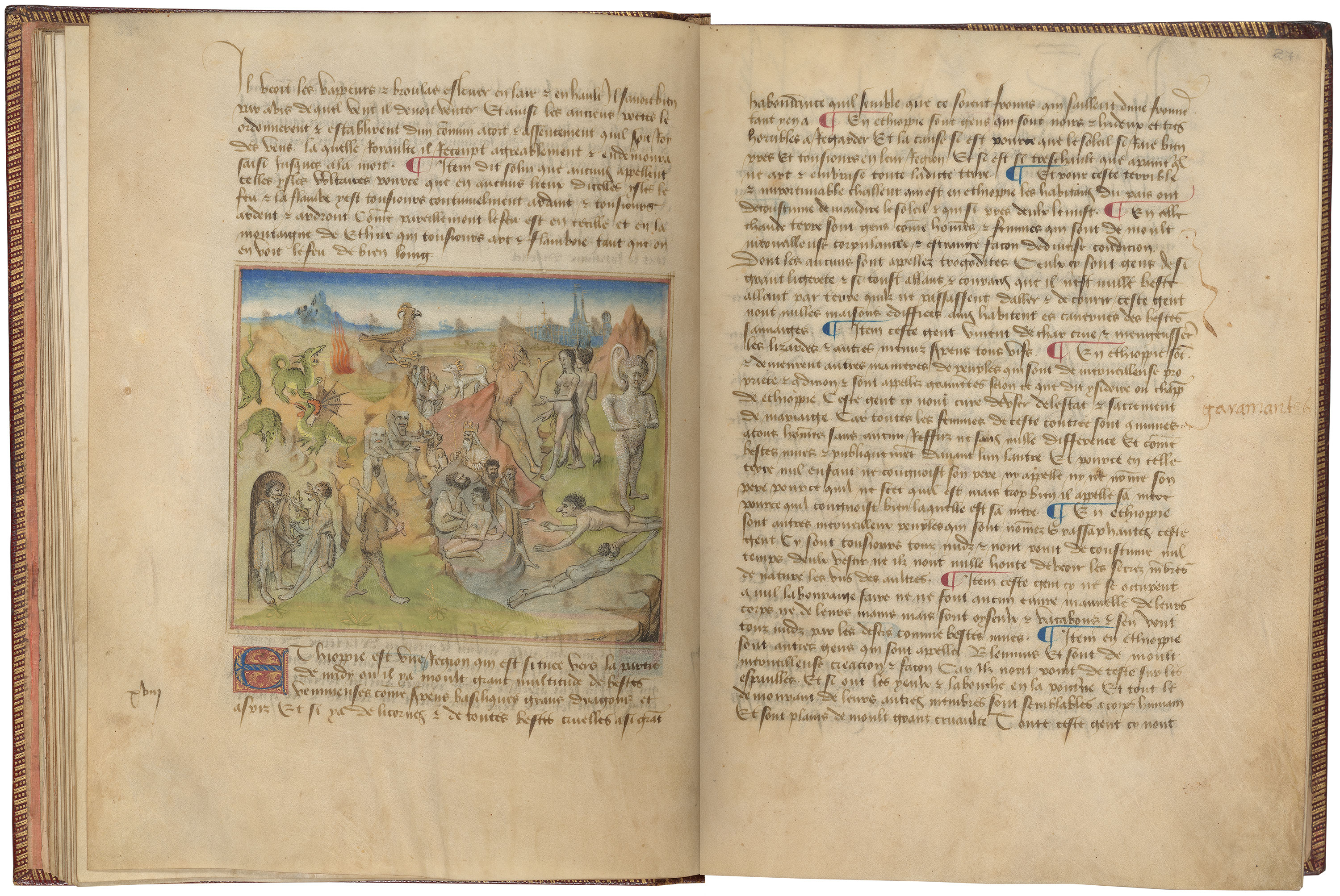

As visual devices, Wild Folk were reduced to a few identifying features, but they were symbolically dense: Wild Folk were described in European legends as violent, ungodly beings who physically resembled humans in all respects save their hairiness and quadrupedalism. They were thought to inhabit European forests and remote mountains, reinforcing Europeans’ beliefs about their own civility by contrasting it. Wild Folk were also associated with the so-called “Monstrous Races”—famously described by the ancient Roman philosopher Pliny—which included Pygmies (tribes of diminutive people), Troglodytes (cave dwellers who lacked language), and Cynocephali (dog-headed people). The Monstrous Races were imagined to exist on the fringes of the known world, and their debated status as either humans or subhumans provoked consternation amongst medieval Europeans. Finally, ideas about Wild Folk and the other Monstrous Races anticipated transformations that would occur over subsequent decades. Geographic expeditions and the deforestation of Europe would demystify the peripheral spaces where Wild Folk and the Monstrous Races had been localized, leaving their mythological dressings in search of new wearers. Ultimately, the visual signifiers of Wild Folk were repurposed for early representations of Indigenous people in the Americas, a strategic move that supported the logic of colonialism through the dehumanization of Indigenous bodies.

Wild Folk were thus fictions that Europeans projected onto real peoples as a way of managing concerns about and justifying the exploitation of remote Others. The Moor’s head, by contrast, abstracted and fictionalized Others who were known, proximate, and in conflict with Europeans. The pejorative term “Moor” was formulated to describe Muslims against whom Europeans were waging holy war. The Crusades, Reconquista, and Ottoman wars—fought from the 11th through 19th centuries to extend Christendom in Europe and beyond—crystallized for Europeans their status as defenders of the Christian faith in opposition to the perceived heathenism and enmity of Muslims. In order to exaggerate the portrayal of Moors as antagonists, they were often depicted as Black Africans, building upon long-standing Christian associations of darkness with inherent sin. The hybrid symbol of the “Moor” (an image conflating religious and racial difference) proliferated in European heraldry as a means of caricaturing and disempowering a menacing foe. It celebrated military victories over Muslim armies and magically guaranteed future triumphs, all while essentializing Blackness as subhuman, demonic, and not just visually but racially Other. The heraldic “Moor” thus contributed to the beginnings of European hierarchies of race and myths of white supremacy that continue to have devastating consequences today.

Adding to the complexity of the tapestry’s representations is the fact that Wild Folk were often elided with Blackness and Moors. Wild Men were described as “black like Moor[s]” by medieval poets Chrétien de Troyes and Hartmann von Aue, and they were located in Africa in certain manuscript illuminations (see “The Monstrous Races of Ethiopia” in Livre des merveilles du monde c. 1460). Although Wild Folk and the “Moor” are articulated as distinct symbols in LACMA’s tapestry, they interweave fluid narratives of Otherness that Europeans would attempt to concretize in the centuries that followed. Collectors of the 17th century—descendents of those who might have originally commissioned tapestries such as this one—tried to classify non-Europeans according to self-serving frameworks, part of a larger attempt to impose order onto the confusion of the known world. This world-ordering project would harden biases into structures of racial difference. By scrutinizing the tapestry and other objects assembled for The World Made Wondrous: The Dutch Collector’s Cabinet and the Politics of Possession, we can begin to unravel the histories of these structures and to think critically about the complicated legacies that line the walls of modern museums.

The World Made Wondrous is on view in the Resnick Pavilion through March 3, 2024.