Last year, soon after we acquired the portraits of Chippewa Chief No-Tin by Henry Inman and Charles Bird King, I began making plans to organize a public program to explore the identities, histories, and art histories these images embody and prefigure. I wanted to find noted authorities who could help elucidate fact from fiction and consider artistic license in relation to history. At our roundtable on Saturday, "The American Indian and American Art," we heard from William Truettner and Amy Scott, curators at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Autry National Center, respectively, as well as Mateo Romero, a Cochiti Pueblo painter based in Pojoaque Pueblo and Santa Fe, New Mexico. Their talks brilliantly tackled issues raised by American Indian imagery in American art in the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries, and raised important questions that we will all be thinking about for a long time to come when looking at historical to contemporary images of Native Americans.

Henry Inman, No-Tin (Wind), 1832-1833, Gift of the 2008 Collectors Committee

A central theme throughout the talks was the contingency of images of American Indians, especially by non-Native American artists, as the title of Mr. Truettner's talk on nineteenth-century paintings suggests: "Why Real Indians Never Appear on Canvas." However, in Mateo Romero's contemporary art, both appropriated and real Indians appear in his canvases.

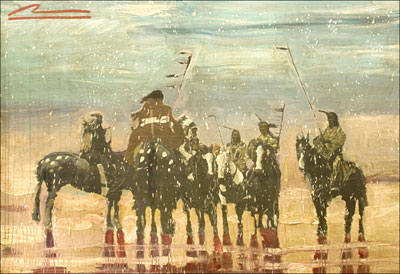

Mateo Romero, War Music II, 2008, © Mateo Romero

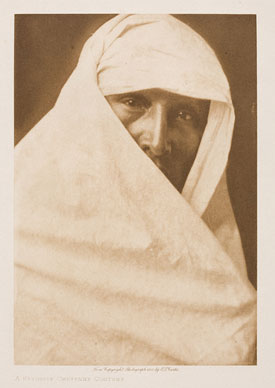

In some of his works, like War Music II (2008), just acquired by the Autry National Center after being exhibited in their 2008 exhibition, Maverick Art, Mr. Romero incorporates photo transfers of historical Edward Curtis photographs into his work.

Edward Sheriff Curtis, A Favorite Cheyenne Costume, 1911

In other paintings he depicts living Pueblo village traditions of song and dance that portray individual Pueblo Indians, such as the young dancer named Butterfly in the eponymous 2007 painting.

Mateo Romero, Butterfly, 2007, © Mateo Romero

In response to questions from the audience about authenticity of American Indian images, Mr. Romero responded, "I am authentic." And Mr. Truettner stressed "from whose standpoint is something authentic?" Ms. Scott acknowledged the interconnectedness of "representation and power and expectation and response": it is essential to assess how representations of American Indians are determined by who is making the image, and for whom, and to consider the audience for the work and the historical moment of creation and reception through history. And how does portraiture broadly considered—of American Indians, their land, their cultures—try to negotiate the past, present, and future? In what ways today can historical and contemporary American Indian imagery obscure, preserve, or mediate Indian cultures for non-Indian and Indian viewers alike?