As vigorous in his provocations as he is in his formal inventions, Nagisa Oshima is a filmmaker who has always stood apart. An omnidirectional spigot of j'accuse fervor (chiefly aimed at Japanese nationalism) with a pair of Scope-spanning kino-eyes, he deserves to have the breadth of his eclectic oeuvre more substantially recognized. Long unseen, if ever, in Los Angeles, thirteen of Oshima's films, from his 1959 debut (A Town of Love and Hope) to his 2000 swan song (Gohatto), will screen at LACMA starting tomorrow.

In anticipation of this retrospective, I exchanged emails with the film series's curator: Cinematheque Ontario senior programmer James Quandt. Quandt has been the recipient of a Special Prize for Arts and Culture from the Japan Foundation and editor of definitive volumes on Shohei Imamura and Kon Ichikawa. He's not only renowned for his erudite, prolific writing but also for curating among the most thorough film retrospectives in North America. In the Realm of Oshima is no exception.

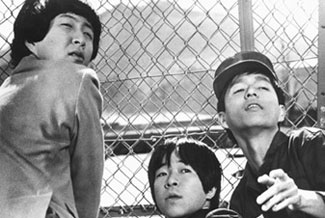

The Ceremony

Q: It’s been two decades since a retrospective of Nagisa Oshima’s films was last held in North America. In fact, you were also the curator of that preceding series, which took place in 1988 at Toronto’s Harbourfront Centre. What are the major differences between that series and what you’ve put together now?

A: This one is more comprehensive; two or three titles were not available the last time, and, of course, Oshima has made several films in the two decades. More important, many of the new prints in this retrospective are recently struck or brand new; the Harbourfront retrospective had to rely on extant prints, many of which were not in good condition.

Three Resurrected Drunkards

Q: Oshima himself attended the ‘88 retrospective and the two of you kept up a correspondence for some years. Can you tell us a bit more about your relations with a director often deemed “difficult” by many?

A: Indeed, I had been warned off inviting him by many colleagues, but, as often happens in such cases, he proved to be the total opposite of his reputation: sweet, funny, generous. We maintained a correspondence for some years after and because one of the producers of his next film (never made, alas), about Sessue Hayakawa, was in Toronto, he sometimes dropped by to visit.

Q: Have you had any direct contact with Oshima about this present retrospective?

A: No, Oshima suffered a debilitating stroke some years ago, and is not aware of the retrospective.

Q: Can you discuss a bit more what you call the “vexing rights issues” that long delayed this Oshima retrospective and thwarted so many others from mounting such series in the past twenty years?

A: Some of this must remain private, but suffice it to say that the rights on many of Oshima's key films, especially from the sixties and seventies, have been contentious, uncertain. I thank my colleague Marie Suzuki at the Japan Foundation, Tokyo, a true miracle worker who finessed what had long been considered intractable problems to get prints made and the necessary permissions. My psychotic persistence paid off in the end.

Q: You specifically cite Oshima’s television documentaries from the sixties as “impossible” to screen. Can you tell us a bit more about them?

A: Oshima made several very political documentaries about Japan’s history, criticizing the imperial system, the rise of militarism, etc. They incorporated a great deal of newsreel footage. It is truly amazing to me that these were made and shown on Japanese television. That would certainly never happen in North America. I very much wanted to show at least two or three as examples of the form; they're very important works. But my investigations showed that the rights, which are always complicated for public exhibition of television works, were impossible to secure, partly because of the nature of the works (clips from here, there, everywhere). The retrospective has been invited to this year's Torino film festival and they are keen to show some television work so perhaps they will be luckier than I. Of course, I also felt I had to concentrate on getting the rights and prints for the films, which was a daunting enough task.

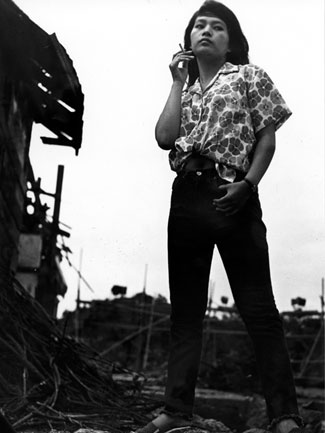

The Sun's Burial

Q: What are some of your favorite films in the series?

A: The pantheon is the pantheon for a reason: Boy, The Ceremony, In the Realm of the Senses. But there are many I love which are not so well known. The Sun's Burial is one of cinema's great visions of hell. And I have mighty fondness for Three Resurrected Drunkards, one of his wittiest and most deeply felt films, though it can drive an audience to distraction.