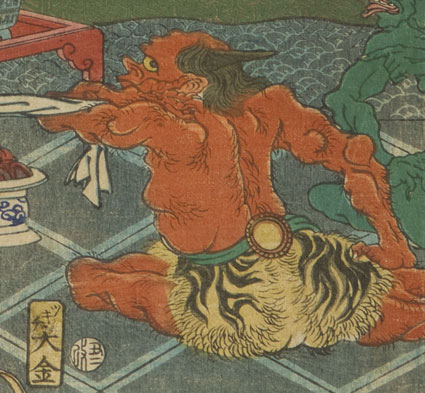

For every work of art on paper featured in an upcoming exhibition, our lab in conservation examines it to determine its condition and whether any treatment is needed. So when we received a woodblock print from Yoshitoshi’s Demons, an installation of works from one of Japan’s top print artists of the Meiji era (opening at LACMA tomorrow), we noticed a disfiguring gray patina over some of the image’s red areas. We immediately set to work trying to figure out whether the gray was intentional or a form of degradation. We know that the red lead used in Japanese prints can react chemically with sulfur in the environment, causing the ink to discolor. Sometimes, this darkening was utilized by the printer intentionally as an artistic tool. But, after comparing our print with copies of the same print in various collections around the world, we knew this wasn’t the case—what we were seeing was discoloration. In addition, traditional representations of this type of scene include a female robed in red and white—not gray and white. After these comparisons and consulting with the curator of the show, we unanimously decided that a conservation treatment was needed. To convert the blackened pigment back to its original red-orange hue, we treated the discolored media with an oxidizing agent. This changed the lead sulfide to lead sulfate and revealed the print’s original color, as you can see in these before and after pictures. In the treated print, the folds of the female figure’s costume are clearly visible, as are the details of the muscular structure of the back of the demon in the lower right corner.

This treatment was an incredibly gratifying experience, as it resulted in a dramatic visual improvement of the print. (By the way, the Freer & Sackler Galleries in Washington D.C. is currently featuring an exhibition on the Tale of Shuten Doji—the subject of our print).