Tomorrow night marks the first of three programs in the screening series Vital Signals: Japanese and American Video Art from the 1960s and 70s (with programs two and three happening on the next two Tuesdays, October 13 and October 20). Looking back to the 1960s and ’70s, when the first generation of artists began experimenting with the increasingly available medium of video, the series offers a chance to recontextualize and revisit early works by many artists found in our permanent collection such as John Baldessari, Vito Acconci, William Wegman, Chris Burden, Paul McCarthy, Joan Jonas, and Gary Hill. It is doubly exciting to learn more about the affinities between these artists and those working at the same time in Japan.

The series, organized in collaboration with the media arts organization Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI) and curators in Japan, shows rarely screened works by artists from the U.S. and Japan and will have some real surprises for even the most avid aficionados of experimental video. The correspondence between American and Japanese artists has often been cited in terms of technological innovations (such as in Nam June Paik’s collaboration with Tokyo-based engineer Shuya Abe), or in terms of influence (for example the role of Noh performance in Joan Jonas’s work). In Vital Signals, however, we are given an opportunity to consider the parallel investigations of artists grappling with a new technology yet working in drastically different milieus.

Some of the works are astoundingly similar, such as in Paik’s Digital Experiment at Bell Labs and the Japanese artists Computer Technique Group, in which early computer graphics and type punctuate the screen.

Nam June Paik, ”Digital Experiment at Bell Labs,” 1966, courtesy of Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

Computer Technique Group, ”Computer Movie No.1,” 1969, courtesy of the artist

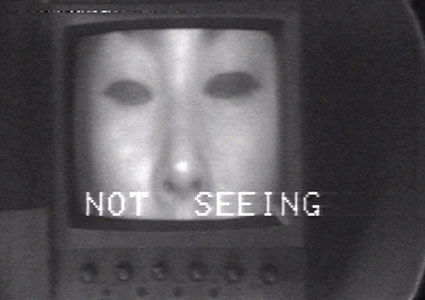

In others we are confronted with the way artist, subject, and representation reverberate. Joan Jonas’s Left Side Right Side shows the artist performing alongside a mirror-image video, while Takahiko Iimura’s Observer/Observed questions who exactly is watching whom.

Joan Jonas. ”Left Side Right Side,” 1972, courtesy of the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

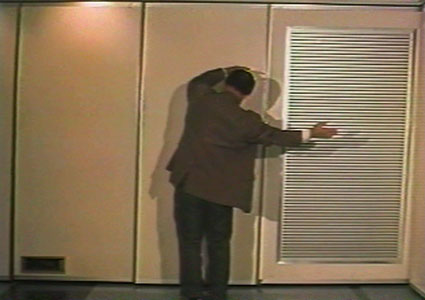

Takahiko Iimura. ”Observer/Observed,” 1975–76, courtesy of the artist

In John Badessari’s Cigar Lexicon the artist tries to build a definition of an object through a series of repeated motions, followed by Hakudo Kobayashi’s Lapse Communication, in which gesture is gradually repeated and broken down into nonsensical movements.

John Baldessari. ”How We Do Art Now,” 1973, courtesy of Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

Hakudo Kobayashi. ”Lapse Communication,” 1972 (revised 1980), courtesy of artist

These kinds of revelations run throughout the series. Tomorrow night will focus on how early video works highlighted the novelty of the medium itself—instantaneous playback, animation capabilities, technological manipulation, etc. Next week’s screening explores how artists worked with television and the increasingly availability of video as a tool for communication, political activism, and commentary on image production. In the final program we will return to the artists’ studios for performances produced specifically for the camera. In all three programs there is a loose conversation between the works in both continents, thus creating an underlying narrative that captures the excitement of artists working at the forefront of technological possibility—a thread we might follow through to our present moment of digitization.

Alex Klein, Ralph M. Parsons Curatorial Fellow