With all the recent buzz surrounding the release of Tim Burton’s new adaptation of Alice in Wonderland, I’ve had fantasylands and fairy tales on the brain. Imagine my surprise when I uncovered beautifully printed fairy tales in our library’s special collections! A handful of our books are relics from the personal library of Paul Rodman Mabury, an early and influential supporter of the original Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science, and Art. You can tell a lot about a person from his library, and it’s clear that Mr. Mabury was interested in fairy tales.

Mabury’s books are my favorite fairy tale volumes here, but they’re not the only ones. Our collection ranges from the late nineteenth century to the early twenty-first century and shows a remarkable range of styles in illustration, type design, and overall presentation. They run the gamut from fine arts press limited editions to mass-produced publications; this breadth of publication types over a century demonstrates the level to which fairy tales continue to inspire independent artistic visions as well as permeate popular culture.

Although fairy tales were originally disseminated by means of oral transmission, the first printed fairy tales began to appear in fifteenth-century Italy and quickly became a staple of the blossoming book trade industry with tales by authors like Straparola and Basile. As printed tales developed as both a genre and a commodity, they continued to reflect the societies in which they were printed. In fact, scholars continually argue the importance of the fairy tale in the burgeoning concepts of national identity and common cultural heritage. Despite plots and tale-types that transcend languages and borders, fairy tale authors and illustrators imbue their unique versions with recognizable traces of the times and societies of which each figure was a member.

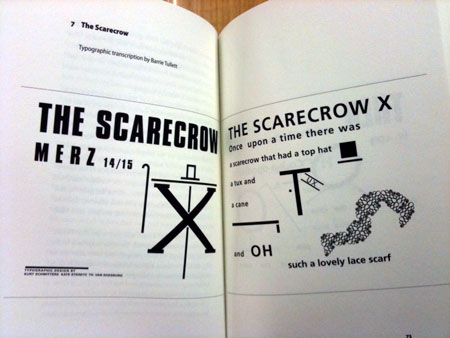

For instance, the books of British artist Arthur Rackham reflect a popular Victorian sensibility, including strong Japanese influence, overwhelming fantastical and floral images, and decorative, color plates. The binding corresponds: Rackham’s fairy tale books were printed by fine arts presses and bound in vellum with gold leaf decoration. On the other hand, the newly reprinted edition of Kurt Schwitters’s “Merz” fairy tales reflects a modernist rejection of traditional storytelling and imagery with tales like “The Scarecrow,” told completely in typographic illustration and, as Jack Zipes notes, “bordering on the grotesque,” rather than conforming to traditionally sweet or childlike imagery of fairy lore.

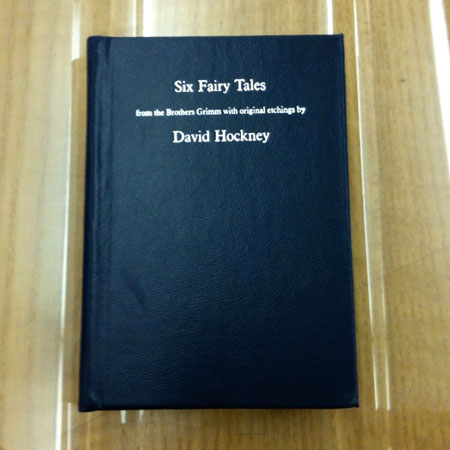

David Hockney’s Six Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm is a combination of modern illustrations alongside an English translation of the Grimms’ German text. This modern vision of the Grimms’ fairy tales was handset and bound in a miniature edition with a keen eye toward recreating bibliographic and physical elements—letterpress printing, high-quality rag paper, colophon—in a traditional fashion.

The printed fairy tale in all of these forms is an artifact that represents more than “Red Riding Hood” or “The Little Mermaid”; these examples represent the significance of the book form in cultural phenomena like storytelling. Although oral tales retain properties of fluidity, these printed tales are moments of fixity—unique artistic visions that encapsulate specific cultural movements and sensibilities. It’s worth visiting the library to see them; I’d love to share them with you!

Maggie Hanson, Stacks Manager, Balch Research Library