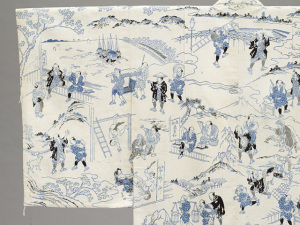

On view in the Pavilion for Japanese Art is a summer kimono, known as a yukata—a cotton plain weave kimono worn both by men and women, which evolved from a bathing robe. Printed in woodcut on this kimono is the acclaimed novelist Jippensha Ikku’s nineteenth century masterpiece, Hizakurige (meaning “journey on foot”). The garment is covered in a hundred and ten or so individual woodcuts that depict the humorous and lusty adventures of the two madcap characters, Yaji and Kita, as they travel on Tokaido Road, from Edo (Tokyo) to Kyoto.

Summer Kimono (Yukata) with Illustrations from the 180 novel ‘Hizakurige’ (Shank’s Mare) by Ikku Jipensha (1765–1831), Edo period, early 19th century, Costume and Textiles Deaccession Fund

The scenes are beautifully spaced and ironically, one is unable to establish the beginning, not that it’s necessary. The garment could well represent a time of this late Edo period where the populace was allowed to search for enjoyment, which became known as ukiyo (the floating world). It was a time when the arts flourished in all forms: music, popular stories, puppet theater, and literature. Tourism was the rage. It was the world of inns and teahouses and festivals. Beautiful woodcuts were very popular, thus one can imagine the joy of following the vividly animated two Buster Keaton-like characters on the kimono as they comically pratfall from one scenario to another, while making the journey oneself.

Detail, Summer Kimono (Yukata) with Illustrations from the 180 novel ‘Hizakurige’ (Shank’s Mare) by Ikku Jipensha (1765–1831), Edo period, early 19th century, Costume and Textiles Deaccession Fund

In the retrospective Pure Beauty —closing this weekend—John Baldessari’s narrative is a many splendored thing, to borrow an expression. Here in Duchampian voodoo, the very narrative itself is the game, the foil, the silent film hero or dangling participle, the malapropism; or it’s on the make, mendacious and coy, cunning and yet beautiful in its geometric melodrama of black frames like a femme fatale; and, of course, it’s fun and games.

Not unlike his nineteenth-century counterpart, Baldessari represents his time and the collective fissure that says so much about living in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. To quote him; “I stopped trying to be an artist as I understood it and attempted to talk to them in the language they understood.” Of course this is only slightly disingenuous, for sometimes he achieves the “full Monty,” revealing our foibles and narcissistic dreams. Ultimately Baldessari’s prescient art captures our ad-enriched, Hollywood soaked, media-choked mixed messages with its amusement, its meaning scrambled or hidden in puzzles or laying in wait to be scratched out or searched within other images. Russell Ferguson suggested as much with his perceptive essay title in the book for the exhibition, “Unreliable Narrator.”

John Baldessari, “Hope (Blue) Supported by a Bed of Oranges (Life): Amid a Context of Allusions,” 1991, Tate, purchased with assistance from the American Fund for the Tate Gallery and Tate Members 2004, © 2009 John Baldessari, photo © Tate, London, 2009

And yet for us, having been so well trained, some of the work has lost its wow factor, which ironically exists in a time and a reality that most suits its expression, the digital age. Nevertheless, Baldessari’s inventive and ceaseless energy drives his narratives—enticing and alluring and unsparingly humorous. In that way it reminds me of Jippensha Ikku’s narrative. Though the author’s portrayed narrative on the surface seems simple, the world one senses from the garment is a world of freedom, joy, a kind of cultural play, unselfconsciously delighted in and savored.