In anticipation of photographer Ken Gonzales-Day’s lecture on Edward Kienholz’s Five Car Stud this Sunday, we sat down with the recent Photographic Arts Council (PAC) Prize–winner to discuss his work—including Profiled, his 2011 PAC Prize publication—and how it relates to the politically engaged Five Car Stud. In Profiled, Gonzales-Day examines the construction of Western ideas of race and identity from antiquity through the twentieth century by photographing portrait busts. Though the busts themselves are very much relics of previous centuries, Profiled is as much about the present as it is about the past, providing a new perspective on what it means to be profiled in our own time.

What was it about the sculptural bust—perhaps the most unfashionable form of portraiture in contemporary art—that you found so interesting? What did you think you would discover by photographing these sculptures?

While in residence at the Getty Research Institute in 2008, I would see visitors walk past the portrait busts with hardly a passing glance. I wondered why these works had become so illegible to contemporary audiences that they scarcely saw them. At the time, I was doing research on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century texts dealing with race, as well as texts that included racial depictions. In Profiled, I wanted to try to trace the emergence of racial categories themselves as a scientific “fact.” I had hoped that photographing the busts might give me a new perspective on the research and perhaps provide some new insights that I had missed in the more academic research. I was looking for little clues that pointed to the ideological underpinnings of the work. I wondered what ideas influenced the artists or had driven the commissions in the first place.

Ken Gonzales-Day, Untitled, 2011, featuring Ubangi Woman, Malvina Hoffman Collection, The Field Museum, Chicago; Head of a Woman, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, CA, © 2011 Ken Gonzales-Day

Photography allows you to construct a particular way of seeing these sculptures. How did making use of the “mug-shot” convention add to your thinking about your subject?

Initially I began by shooting everything in profile, as a way of foregrounding the early emphasis on the analysis of the facial profile so favored by the so-called pseudo-scientists [the mug-shot profile was a photographic mode invented in the late nineteenth century to document and categorize criminals and “deviants”], but it was also a play on the idea of “profiling” the museum’s collections themselves. After all, what do these collections reveal about the institutions themselves and their very real origins in the same Enlightenment project that fostered and supported the creation of racial categories—or types—in the first place? They were literally being profiled as a kind of institutional critique—but one that extended beyond any single institution or collection and that strove to provide a critical look at a number of representational strategies (or styles).

Ken Gonzales-Day, Untitled, 2011, featuring Bust of A Young Man, Antico (Pier Jacopo Alari-Bonacolsi), and Bust of a Man, Francis Harwood, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA, ©2011 Ken Gonzales-Day

How did producing a book affect the project as a whole? Does the book provide an alternative way of viewing and understanding the body of work in a way that an exhibition or simply viewing the images online might not?

The project evolved as the book evolved. The LACMA PAC Prize provided an amazing opportunity to work on a project in depth. Ultimately, the book project allowed me to place objects together in a way that would never be possible in an exhibition. Certainly, some of the works would never be lent for an exhibition, and many of the works can only be found in storage vaults. In organizing a book, I was able to lay out a visual journal that would be difficult to replicate in a museum space.

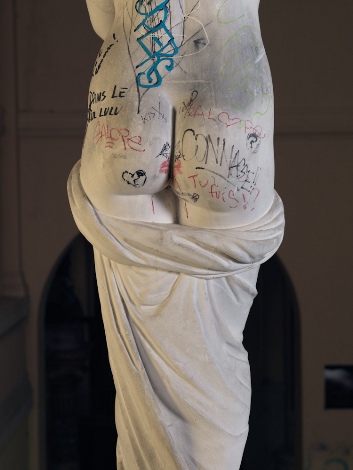

Ken Gonzales-Day, Celestial Venus, 2011, featuring a cast from the antique in Uffizi, École des Beaux-Arts, Paris, © 2011 Ken Gonzales-Day

You are about to give a talk at LACMA on Ed Kienholz‘s Five Car Stud as well as your previous work in which you photographed trees that had been the site of lynching. There are clear parallels there. In what ways might you see your work, and Profiled in particular, as akin to Kienholz’s?

Five Car Stud depicts the castration of an African American by a group of presumably white men, as a white woman and a young child look onto the violent scene. The sculptural depiction of a lynching in 1972 is clearly a political statement. For Kienholz, it spoke to the inequality faced by blacks in the United States. Today, it remains a powerful and disturbing work, but it must also be located within the larger discussion of whiteness, and, for me, it must also be located within the larger discussion of racial depictions in sculpture. After all, what is it to see this image—a three-dimensional re-creation of a racist fantasy—in a city where Latinos were lynched more than any other race? Five Car Stud is a sculptural depiction of racial violence, and, as a result, the images of Five Car Stud stand at the intersection between both the Profiled project and my previous work on the history of lynching in California. I am still working though a great many questions around the work, and I am definitely looking forward to hearing what people think about it.

Ryan Linkoff, Ralph M. Parsons Curatorial Fellow, Wallis Annenberg Photography Department