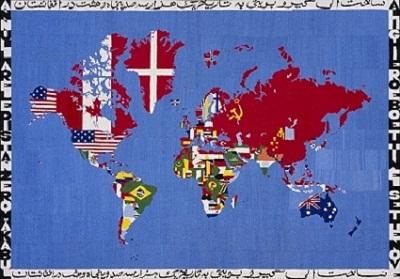

The exhibition Common Places: Printing, Embroidery, and the Art of Global Mapping features embroidered objects with global themes, inspired by works on paper. Included in the exhibition is LACMA’s Mappa (1979), a work conceptualized by Italian artist Alighiero Boetti and embroidered by Afghan women, which takes the geopolitical map as its subject. From 1971, Boetti’s embroidered world maps were produced serially in Kabul until the Soviet invasion in 1979; thereafter, production shifted to Afghan refugee camps in Peshawar, Pakistan, where it continued until Boetti’s death. In 1990 American photographer Randi Malkin Steinberger travelled to Peshawar to capture the creation of these embroidered artworks. She and Boetti subsequently selected and organized her photographs for a publication, just recently released as Boetti by Afghan People: Peshawar, Pakistan 1990.

Alighiero Boetti, Italy, Mappa, 1979, purchased with funds provided by The Broad Contemporary Art Museum Foundation in honor of the museum’s 40th anniversary

Here, Malkin Steinberger talks about the complex process of making the maps, winning access to the embroiderers in Peshawar, and what it was like to collaborate with Boetti.

In terms of the production of the embroidered maps, how was labor divided between Italy and Afghanistan/Pakistan?

Boetti planned the design and oversaw the transfer of the colored map to the cloth ground. At first one of his assistants projected and hand-drew the outline of the map onto the textile, but by the time I became involved, they were applying color-coded outlines by silkscreen. Once this step was done, the printed cloth was sent from Italy to Pakistan. The embroiderers were just instructed to use simple stitch techniques. Over time, they were free to make some decisions regarding thread selection, particularly when it came to the ocean—some oceans were black, yellow, green, and even pink. He really liked their color sensibility. Each map took a long time to make—from months to years depending on the size—and several women often took turns over the course of its production, or at times two or three worked together on the same map. When the maps were complete, they were inspected by an assistant before leaving Pakistan and finally by Boetti when they returned to Italy.

Randi Malkin Steinberger, Afghan Women Working Together on a Boetti Mappa, 1990, © Randi Malkin Steinberger

What kind of contact did Boetti have with the women who made his artworks?

When the maps were made in Afghanistan, he visited at least twice a year but after the move to Peshawar he no longer had direct contact at all with the women. Things were different there—society adhered to strict Muslim codes of conduct so men had limited access to women in the camps. Boetti’s assistants traveled to Peshawar but they only had indirect access through the women’s male relatives. But there were other small points of contact. The edges of the map intended for Persian text were left blank during the silk-screening process, and Afghan male collaborators could choose their own message—sometimes thanking Boetti or wishing him well, and other times including their signatures as artists, authors of the work. He loved seeing the pictures I came back with because at that point it had been years since he’d seen the women holding the embroideries.

Being a woman, was it easier for you to gain access to the embroiderers?

It was somewhat easier for me than a man, I guess. But the political situation in Peshawar was tense, and camp officials were very suspicious of Westerners so I had to dress in clothing that was typical of the region in order to blend in. I only had two weeks in Peshawar, and I was really anxious to get inside the camps. I finally did, but I had just one day there, so I had to shoot fast.

Luca Pancrazzi, Randi in Peshawar, Pakistan, 1990, © Luca Pancrazzi

The maps were just one of Boetti’s many collaborative projects. Your photographs also resulted from a similar partnership. What was it like to work with him?

He didn’t want to instruct too much. He loved to see what people would do, how they might improvise within certain guidelines. When I first started working with him photographing his studio in Rome, he just said, “Come by any time.” Then one day he said, “You know, it would be great if you could go to Pakistan and take some pictures.” Afterward, I would show him the photographs, and he would pick the ones he liked but didn’t always explain why. Working with him was often very nonverbal. As far as the embroidered maps go, he liked the spontaneity of working from a distance with unknown artisans he’d never met. I’m not sure how the Afghan women felt, since I couldn’t really communicate with them at length, but I could tell they admired him a great deal and appreciated having the opportunity to do the work. I think he saw the embroiderers as his “opposite”—he was fascinated by the concept of twinning and opposites mirroring each other.

Common Places: Printing, Embroidery, and the Art of Global Mapping is on view in the Ahmanson Building through May 13. Boetti by Afghan People: Peshawar, Pakistan 1990 is available for purchase at Art Catalogues, also in the Ahmanson Building at LACMA.

The Fowler Museum at UCLA is also presenting an exhibition of Boetti’s artistic collaborations with Afghan embroiderers entitled, Order and Disorder: Alighiero Boetti by Afghan Women, featuring several works by Randi Malkin Steinberger as well.

Nicole LaBouff, former Wallis Annenberg Curatorial Fellow, Costume and Textiles