[Find continuing updates on the transport of the boulder for Michael Heizer's Levitated Mass here.] In other news: Opening this Sunday, March 11, Robert Adams: The Place We Live, A Retrospective Selection of Photographs presents the artistic legacy of photographer Robert Adams (b. 1937) and his longstanding engagement with the changing landscape of the American West and the lives of its inhabitants. With a timely opening during California’s Arbor Day celebration (March 7–14), the exhibition reveals Robert Adams’s eloquent preoccupation with the presence of trees, featured in series dedicated to the Los Angeles region, cottonwood trees in Colorado, and poplars, alders, and firs growing in Oregon. Edward Robinson, associate curator of the Wallis Annenberg Photography Department, talks to Dr. Matt Ritter, a botany professor at California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo and California trees expert, about the flora of Robert Adams’s photographs. Dr. Ritter will lead a gallery talk about the exhibition on Thursday evening, March 22.

Dr. Matt Ritter

Edward Robinson: Adams began photographing the Southern California region in the late 1950s and early 1960s, returning many times to describe the citrus groves, eucalyptus, and palm trees that flourish in the area. Looking at Robert Adams’s series, “Los Angeles Spring” (1979–83), what do the many different kinds of trees featured suggest about the region’s horticultural history and changing land use over time?

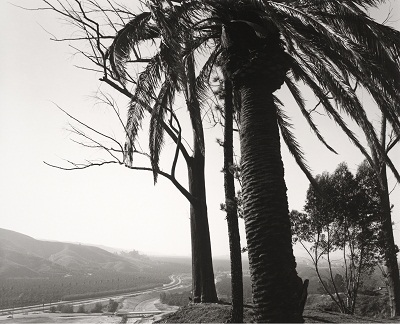

Matt Ritter: At different times in Southern California’s history, certain plants have been more or less horticulturally popular. An example is the Canary Island Date Palm (Phoenix canariensis) featured in Robert Adams’s Edge of San Timoteo Canyon. Although young Canary Island Date Palms are rarely planted anymore, they were very popular around homesteads at the turn of the last century. When the homesteads and agricultural fields were abandoned, destroyed, or developed, these palms, which can live for centuries, remain as reminders of the activities, cultural history, and interests of early Californians.

Not all plants were utilitarian; a large Canary Island Date Palm would have stood proudly as a symbol of status and stateliness in the yard of a farmhouse. On the other hand, Red Gum eucalypts (Eucalyptus camaldulensis), the sole species in Abandoned windbreak, were entirely utilitarian and favored by early agriculturalists in Southern California. These trees, which seem to thrive on neglect, offer shade, protection, and wood, and were often the only trees in otherwise desolate and hostile landscapes.

Robert Adams, Edge of San Timoteo Canyon, looking toward Los Angeles, Redlands, California, 1978, Yale University Art Gallery, purchased with a gift from Saundra B. Lane, a grant from the Trellis Fund, and the Janet and Simeon Braguin Fund

Robert Adams, Abandoned windbreak, West of Fontana, California, 1982, printed 1996, Yale University Art Gallery, purchased with a gift from Saundra B. Lane, a grant from the Trellis Fund, and the Janet and Simeon Braguin Fund

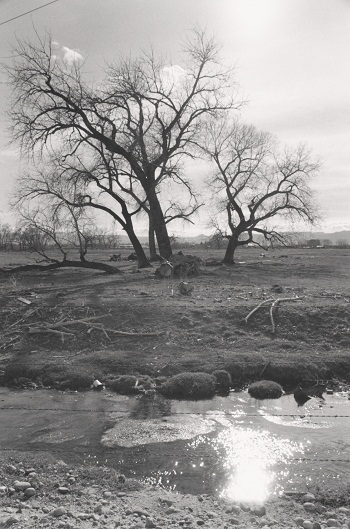

ER: Other series on view describe the cottonwoods in Colorado, where Robert Adams lived for much of his career. Adams writes that “Cottonwoods have been our friends for a long while. The Arapaho believed that the stars came from cottonwoods, from the glistening sap at the joints of twigs. Immigrant wagon trains followed along from one grove to the next, with cottonwoods serving as landmarks, shelter, and fuel.” What is distinctive about cottonwoods as a species of trees and an element today of the inhabited west?

MR: It is not surprising that cottonwoods (Populus fremontii) caught Adams’s eye. They are like few other trees in the American West, with their twisted, wide-branching forms, corrugated, gray-skinned trunks, and leaves that ripple in the wind. They are the patriarchs of the landscape—survivors in a place of drought, heat, and shattering cold. Inhabitants of the American West have always known cottonwoods to be indicators of precious resources. They grow where water is available, in fertile alluvial bottomlands. Cottonwoods in the distance are a promise of arable land, water, food, shade, and better times.

Robert Adams, Untitled, from the series Along Some Rivers, 1985–87, Yale University Art Gallery, purchased with a gift from Saundra B. Lane, a grant from the Trellis Fund, and the Janet and Simeon Braguin Fund

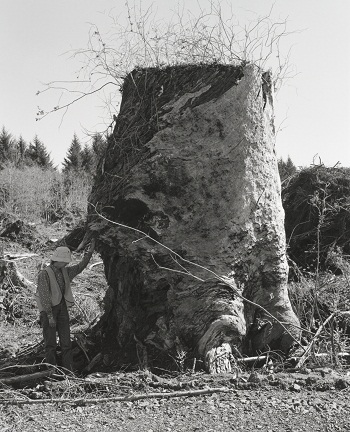

ER: For the last fifteen years or so, Adams has lived in Oregon. His series “Turning Back” is dedicated to the subject of deforestation in the Pacific Northwest. One of Robert Adams’s photographs features his wife, Kerstin, standing beside a large stump, a remnant of an ancient wood where trees once commonly grew to be five hundred or more years old; others depict the “harvest” of newer forests. What is your sense of the future of the rainforests in the region?

MR: I grew up in a rural part of Mendocino County in Northern California, where logging the remnant coastal redwood forests was one of the main industries in the area, and I witnessed those logging activities change greatly in a relatively short period of time as the trees disappeared. In my part of Northern California and the parts of Oregon depicted in Robert Adams’s photographs, there is so little of the original, virgin, old-growth forests remaining (less than 4 percent).

The wholesale plunder of California and Oregon conifers that took place in the early part of the twentieth century is over, but the scars remain. These scars take form in the infrastructure: abandoned towns, mills, railroads lines, and logging roads, and the human-modified ecosystems of Adams’s photographs: half-rotted, massive old stumps, second-growth forests, and slowly recovering waterways and fisheries. Fortunately, most old-growth rainforests of the Northwest are protected in perpetuity, and logging practices have improved greatly, with many companies finding new ways to sustainably harvest timber.

Robert Adams, Sitka spruce, Cape Blanco State Park, Curry County, Oregon, 1999–2000, Yale University Art Gallery, purchased with a gift from Saundra B. Lane, a grant from the Trellis Fund, and the Janet and Simeon Braguin Fund

Robert Adams, Kerstin, Next to an Old-Growth Stump, Coos County, Oregon, 1999–2003, Yale University Art Gallery, purchased with a gift from Saundra B. Lane, a grant from the Trellis Fund, and the Janet and Simeon Braguin Fund

ER: Robert Adams writes, “Art should finally be encouraging. That’s the promise that brings people to museums. And since lies are finally discouraging, that means art should be truthful. Truthful and affirmative, presumably even about what has happened to most of the landscape.” Amid LACMA’s twenty-acre campus, visitors can also experience firsthand artist Robert Irwin’s Palm Garden, an installation of some one hundred palm trees, designed with landscaper Paul Comstock. Bringing together more than thirty varieties of palm trees and other specimens, Irwin has noted that certain cycads for the site are among the first plants on earth. As the author of A Californian's Guide to the Trees Among Us (Heyday Books, 2012), and thinking about the importance of trees to local and worldwide communities, what do you think some of the most exciting and rare plantings to look for are when visiting LACMA?

Robert Irwin, Palm Garden, 2010, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, © 2012 Museum Associates/LACMA

MR: Robert Irwin’s Palm Garden is a truly impressive collection of trees. Not only does it have one of the greatest diversities of palms in any collection in California, it also houses a number of rare cycads. Cycads, although ostensibly like palms, are actually distantly related ancient plants that evolved during the time of the dinosaurs and have changed very little in the last 250 million years. They have declined in abundance in the places where they occur to a point now where all three hundred species of cycads in the world are rare and endangered in the wild.

Robert Irwin, Chilean Wine Palm (Jubaea chilensis), Palm Garden, 2010, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, © 2012 Museum Associates/LACMA

A particularly awesome individual in the palm collection is the Chilean Wine Palm (Jubaea chilensis) planted in a submerged position near the elevator to the Pritzker Parking Garage. Individuals of this species are the widest palms in the world. If its massive trunk is cut, a sugary sap will flow from it for a long time—hundreds of gallons of syrup can be harvested. In Chile, where the palms are now protected and rarely cut down, this syrup was fermented into a sweet wine. Chilean wine palm fruits are also edible and similar in appearance and taste to small coconuts (called coquitos in Chile). Riding the LACMA’s plaza elevator and observing this massive tree is a special treat during a visit to the museum and palm collection, and you may even get to eat a coquito.

Robert Adams: The Place We Live, A Retrospective Selection of Photographs opens March 11. Members get a sneak preview today, Friday, and Saturday.

Edward Robinson, Associate Curator, Wallis Annenberg Photography Department