On the third floor of the Ahmanson Building, you will find the beautiful engravings of Hendrik Goltzius in LACMA's prints and drawings collection. Goltzius is long considered one of the great draftsmen and engravers of the mannerist style. Equally amazing is his most ravishing painting, The Sleeping Danae Being Prepared to Receive Jupiter, which displays his exuberant touch and transformation from engraving to painting. For me, he is one of the Netherlands’s greatest artists, and represents the mannerist era as a complete expression of the time more than any other artist.

Hendrik Golzius, The Sleeping Danae Being Prepared to Receive Jupiter, 1603, gift of The Ahmanson Foundation

It’s the mid- to late-sixtenth century, the time of the Counter-Reformation and a militant Catholicism. It was ironically also the Age of Discovery. Religious wars raged across Europe, and to some extent in the arts—religious subjects went out of fashion. And out of a mix of complex artistic, political and economic reasons, mannerism emerged. It was seen as “artificial,” and hence “mannered,” being more concerned with pure inner vision and the fantastic. Mannerism, to me, was one of those marvelous moments in the history of art when tradition and naturalism meet obstinate artistic genius to create an emotional charge and change—a modernist inkling. A new spirit, so to speak, was afoot. It is said all kinds of greats fell within its spell: Michelangelo, Titian (with his ravishing Venus of Urbino), Tintoretto, and the utterly hallucinatory El Greco.

Hendrik Golzius, The Judgment of Midas, 1590, Mary Stansbury Ruiz Bequest

Mannerism’s various attributes, such as unreal light, exalted emotionalism, odd placement, and strange perspective, flew in the face of those twin authorities: nature and the ancients. One readily sees mannerism’s essential elements in Goltzius’s The Judgment of Midas: elongated proportions and highly stylized poses. These allegories were commissioned not only for their titillating art, but also to send a message—in this case about Pan’s vanity, and Midas’s donkey’s ears (“earned” for his failing to honor the nature of authority). It is a simple, lush engraving, where sumptuous gowns and figures of fable—such as the Muses—surround nude, muscular Apollo as Pan foolishly competes with the god who literally glows.

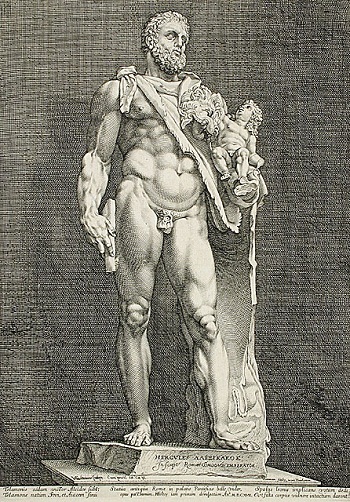

Beside the engravings, there are the woodcuts of Hercules in the midst of his tenth labor, killing the fire-belching monster Cacus. Or Hercules and Telephos, symbolizing the hero’s spiritual strength which was desired and possibly reflected by those in power.

Hendrik Goltzius, The Emperor Commodus . . . Hercules, 1591, Mary Stansbury Ruiz Bequest

Hendrik Goltzius, for a deeply personal reason, would make a journey from Haarlem to Germany and Italy that would have a profound effect on him. Nothing so reminded me of Michelangelo and Durer than Goltzius’s engraving Emperor Commodus … Hercules. Pointedly, he no longer used the exaggerated mannerist style.

However, the sensuous and decadent allegorical themes would find bold expression in his paintings, which he took up in his middle age. His extraordinarily sensitive sense of detail gives one the feeling that here’s an artist using a brush with the same ease as he wielded the burin, his steel engraving tool.

The exquisite, delicate touch he brings to his masterpiece, The Sleeping Danae Being Prepared to Receive Jupiter, is even more impressive when you consider his malformed hand, burned when he was a baby. Its plainly telling didactic is about sex and money. Yet Goltzius’s beautifully rendered message is understandably somehow lost to our modern eyes, which focus on the captivating flesh, the plush and exacting details, the floating putti who are of such a lightness that the semi-tragic myth is made somewhat winsome as the gold coins cascade down upon Danae. The sensuously dreamy repose as seen through the eyes and touch of a master is made stunningly present.

Hylan Booker