Fracture: Daido Moriyama features both black-and-white and color photographs from the renowned Japanese photographer’s career, which spans more than four decades. Also presented in the small exhibition is a six-minute clip from a documentary on Moriyama from 2010 titled, Daido Moriyama: Stray Dog of Tokyo. I recently watched the entirety of this clip for the first time, even though it was probably my fifth or sixth visit to the exhibition.

One thing, in particular, stood out to me: at one point, Moriyama says “I don’t know how you say ‘nasty’ in English . . . But I want to take a lot of nasty photos. It’s that kind of thing for me.” He goes on to discuss how women are sexual but also how the city itself is inherently sexual. Not finding his photographs to be particularly sexual the first few go-arounds, I decided to revisit them in light of this revelatory information.

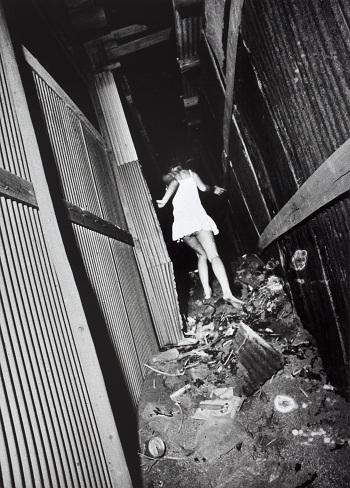

Daido Moriyama, Kariudo (Hunter), 1971, printed 2009, courtesy of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser, © 2012 Daido Moriyama

I was surprised to discover that this new information did inform my experience of the images. Yet, I didn’t find some photos to be particularly sexual or objectifying until I read the titles. For example, in one of the images I find most compelling, a woman runs barefoot through a narrow alley of debris wearing nothing more than what appears to be a pajama of some kind. She isn’t wearing pants, so you can scarcely make out her underwear. The vantage point of the camera, however, seems lower than what one would expect if a grown man standing up straight were taking the photo. So, it seems, then, that the perspective is that of either a man crouched over, stalking the woman, or that of an animal. The photo is also lit from behind, almost as if there is a spotlight on the woman as she runs away. The title? Kariudo (Hunter). Ah ha! She is, indeed, being hunted. She is sexualized prey.

Daido Moriyama, Scandal, Tokyo, Japan, 1969, printed 2009, the Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser Collection of Photographs, © 2012 Daido Moriyama

Next is another image I have seen countless times but never really thought of as particularly sexual. A very good looking couple is driving in a car. The woman is beautiful, dressed in a fashionable blouse, donning big-rimmed sunglasses. She gazes out of the passenger window. Her beau is handsome, sporting a white T-shirt under a sport coat. You can barely make out a dignified mole on his left cheek. An unlit cigarette dangles from his full lips, as if something interrupted the ritual of lighting it. His gaze is fixed in the same direction as that of his companion. The photo itself is very grainy—almost as if it is from a newspaper or tabloid. The title? Scandal, Tokyo, Japan. Ah hah! She is his mistress! To me, the sexuality in this photo isn't necessarily inherent until you read the title of the photograph. Knowing the title, however, makes the leap to sexuality less fraught.

What’s in a name? A lot, apparently.

There are many other examples in the exhibition of sexuality and sensuality—of female bodies becoming the object of a very certain gaze. And what does this mean? What, as a viewer, are we left with believing about these images?

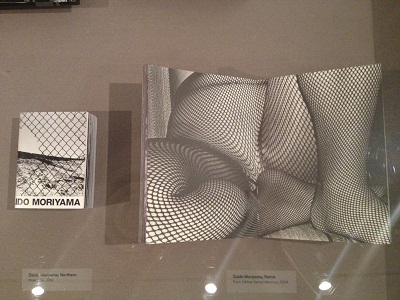

There are catalogues and other bound works featuring Moriyama’s photographs in clear cases in the exhibition. One such work, called Daido Remix, is opened to a spread of a black-and-white close up of a woman’s fishnet-stockinged legs folded, twisted—a labyrinth of dizzying fishnets and flesh that make it difficult at first, along with the mysterious pull of the gutter of the book itself, to ascertain where the legs begin and end, and where, inevitably, this maze leads. The image is sensual, rather than sexual. Suggestive, because your eyes linger, tracing the curves to try to solve the puzzle.

Installation view, Fracture: Daido Moriyama

Interestingly, the exhibition curator chose to juxtapose this image with another on the cover of a book called Daido Moriyama: Northern. The image is a stark black-and-white photograph of a chain-link fence against a barren field. What does it mean that this fence, typically associated with either keeping someone or something in or keeping someone or something out is mirrored by a very suggestive image of a woman’s legs clad in fishnet stockings? Are we supposed to transfer these restrictive/ subjugating associations of the chain-link fence to the tights, and thus to female sexuality? Is the hole in the fence significant? A figurative escape? Is Moriyama a feminist?

Maybe. But, then again, maybe not. You have only until Sunday, July 29, to draw your own conclusions about Moriyama’s work before the exhibition closes.

Jenny Miyasaki