The Unveiling of Femininity in Indian Painting and Photography, a small but poignant exhibition on the fourth floor of the Ahmanson Building, strikes a seemingly eternal chord of the “male gaze” and the “exotic other” in the confluence of cultures.

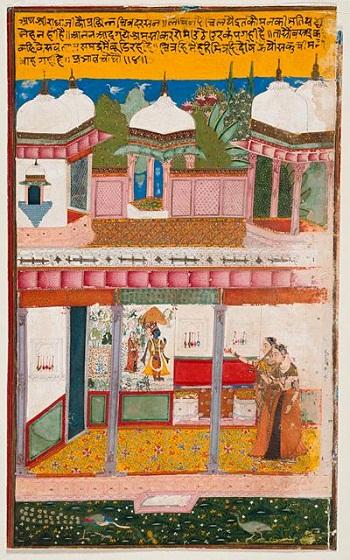

Radha and Confidante Covertly Viewing a Painting, Folio from a Raskapriya, India, Rajasthan, Bundi, circa 1675, from the Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection, Museum Associates Purchase, photo © 2012 Museum Associates/LACMA

In the nineteenth-century photos of William Willoughby Hooper, we must time travel and find ourselves at the height of the colonial British Raj in India. Queen Victoria was on the throne and the predominant mood was of moral and cultural superiority. In the British colonial view, it was more than a business and a fashion; it was an adventure to the Other—one which possibly conceived whole new sciences, such as ethnology, anthropology, and archaeology. In spite of the perceived sophistication, the Indian world was still a mystery to these British aliens. It was an exotic, sensuous puzzle that surely must have played on their Victorian, frock-clad imaginations.

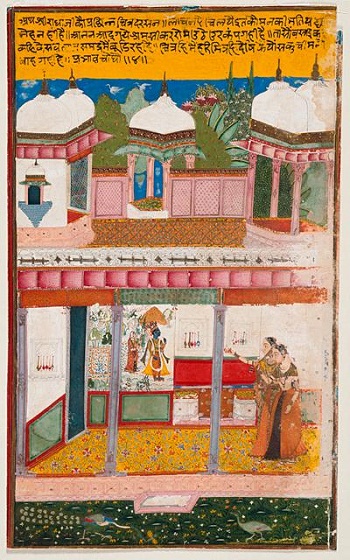

William Willoughby Hooper, Two Nautch Girls on a Bed, c. 1870, Collection of Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck, photo © 2012 Museum Associates/LACMA

As one male’s gaze attempts to sense another, I imagined myself seeing through this British male’s Victorian eyes. And inadequate as that may be (and certainly not to impugn the gentleman), I must assume that like me, he was also mesmerized by these nautch girl dancers—unique, dark beauties clothed and wrapped in silk saris in deep tones of ruby, scarlet, or ochre trimmed in braids of gold. Jewels flow from their noses and foreheads. Earrings clang with gold tasseled bells on their fingers, all blending with the heavy beat of the music.

The intent of the works of Hooper and his photographer-contemporary Charles Shepard may have been to demystify by creating a documentarian reality. Or dare I say, slightly fetishized feminine images. But the mere idea of this Indian, female-centric world was something outside their understanding, and so their works seem only to enrich the women’s very “otherness”—an Orientalist fantasy for the lens.

Perhaps with very little irony we can imagine the Indian male in a somewhat similar position to his British counterpart—he, too, is fascinated by the veiled Other. His male gaze, however, would be deeply rooted in a profound reverence, which must pass through the power of the “ur myth,” the notion of the “mother goddess” on one side and the wrathful, dark Kali on the other. The very concept of the androgynous god Shiva, half woman and half man, compounds the mystery of the female.

These Indian painters imagined life in the zenana (the noble women’s quarters), a world which only the prince was allowed to see, by presenting a voyeur’s idealized reality based on visions from romantic literature and poetry.

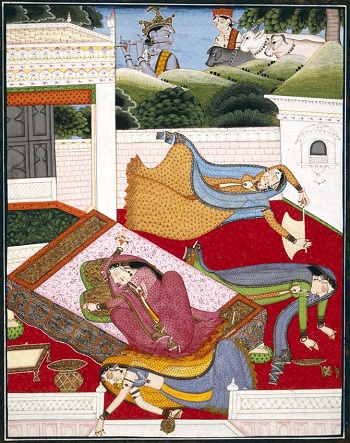

Krishna's Fluting Causes the Palace Women to Swoon, India, Himachal Pradesh, Hindur (?), circa 1830-1840, gift of the Joseph B. and Ann S. Koepfli Trust in honor of Dr. Pratapaditya Pal, photo © 2012 Museum Associates/LACMA

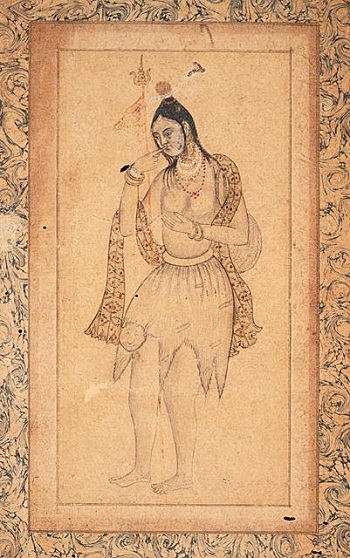

Imagine Indian noblemen looking upon albums with images of these intimate encounters. The god Vishnu’s avatar Krishna, the divine lover, and the romantic heroine Radh illustrate love. Or they peer into the image of swooning women of the palace listening to Krishna’s fluting, or witness a mere mural of Krishna bestowing wonder on the women who gaze upon his divine image. And as if to ground the pictures, the artist painted the almost realistic yogini, the female ascetic. For the Indian nobleman, such scenes of female intimacy would suggest a secret world that would inhabit his imagination.

Female Ascetic (detail), India, Karnataka, Bijapur, c. 1600, Bequest of Edwin Binney, 3rd, photo © 2012 Museum Associates/LACMA

As in Persian paintings, the figures would be bordered in flowers or outdoor scenes of lush vegetation. Bright saris in a variety of colors cast their own spell of paradise. The rich, labyrinthine symbolism of the “feminine principle” depicted—the Shalabhanjika, a beautiful, voluptuous woman whose mere touch makes flowers and fruit bloom; Devi, the female aspect of the divine; or the mother of the universe, Durga, who wages epic battles with the demon king Mahishasur—suggests how strongly this idealized female presence informs even these small, charismatic “unveilings.”

These romantic paintings sit at the source of the Indian male’s almost basic need to gaze upon a hidden treasure—a treasure, ironically, imagined by his own gender.

Hylan Booker