As the Mayanist-in-residence here at the museum, I was asked to write up a few thoughts on the dreaded date, December 21, 2012. The Maya are very much en vogue these days as media outlets across the country play out doomsday scenarios “as predicted by the ancient Maya.” Apparently, according to a recent New York Times article, Russians are frantically stock-piling dry goods and duct tape as well as sculpting Maya pyramids out of ice. As the local expert with my finger on the pulse of Maya scholarship, I can reassure you that scholars around the world agree: the sun will rise on December 22, 2012—which is good, because The Ancient Maya World has only been on view for a couple of weeks so far. But, in the spirit of full disclosure, I am neither an epigrapher nor a calendrical expert (nor very good at math); therefore, for a much more detailed explanation of the complexities of Maya time-keeping, I refer you to Dr. David Stuart’s blog.

Mayanists suddenly find themselves in a rare historical moment as a sought-after commodity. A colleague and I even considered setting up a 1-800 number to address public fears: 1-800-baktuns at your service! Press 1 for why the world will not end. But as I field questions regarding the supposed apocalypse and the precision of the Maya calendar, I find myself asking why, forty years after the decipherment of Maya hieroglyphic writing, which gave voice to an ancient people, do we persist in our fascination with the “mysterious Maya?” Frederick Catherwood’s nineteenth-century watercolors of ruins swallowed by a tangle of jungle vines and palm trees gave rise to this conceit of a mysterious people lost to history.

Frederick Catherwood, the main temple at Tulum, from “Views of Ancient Monuments,” 1844, via Wikipedia Commons

Frederick Catherwood, the main temple at Tulum, from “Views of Ancient Monuments,” 1844, via Wikipedia Commons

Hollywood continues to popularize this image. Films such as the 1963 Kings of the Sun, starring a young Yul Brynner as an upcoming Maya king, the 2006 Darren Aronofsky film The Fountain about the Maya Tree of Life and its life-saving properties, and the apocalyptic 2012, all employ Maya culture as a trope, a signifier for the exotic and the mystical Other. Since the 1960s, scholars have deciphered thousands of inscriptions decorating the facades of buildings, stone sculptures, painted vessels, and even personal items of jewelry (these last ones belong to what we might refer to as the “summer camp literary genre,”e.g., I belong to K’inich Yax K’uk Mo. If lost, please return to Copan).

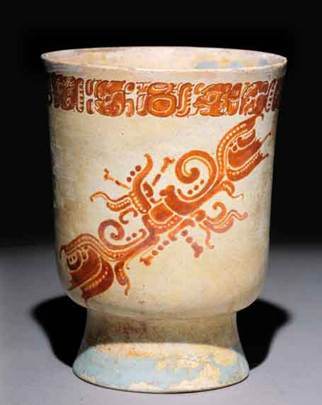

Vessel with Supernatural Profile, Belize, Uxbenka region, Maya, AD 650-900, purchased with funds provided by Camilla Chandler Frost

Vessel with Supernatural Profile, Belize, Uxbenka region, Maya, AD 650-900, purchased with funds provided by Camilla Chandler Frost

These texts enable us to dispel the mysterious mists and fill in the outlines of the ancient Maya world: we have compiled extensive political histories for city-states across the region; we understand who married whom and why; and even what people ate, drank, and consumed recreationally. But still the television outlets ask, “Who built the pyramids?” Well, the Maya did. With stone and forced labor. Another frequently asked question concerns the fate of the Maya, “Where did they go?” The ancient Maya, originators of the complex calendars and misty cities, thrived from 200 to 900 CE across an area corresponding to the present-day countries of Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras. In approximately 900, drought, deforestation, and vicious in-fighting among rival states contributed to a devastating societal collapse that forced the ancient Maya to abandon their urban centers and regroup in the hinterlands. However, Maya culture did not disappear. The modern Maya continue to inhabit the region; over thirty different Maya languages are spoken today. In fact, a number of Yucatec Maya have migrated to northern California and you can sometimes catch the tonal syncopations of Yucatec Maya in Bay Area kitchens.

The Maya captivated my imagination the first time I climbed Tikal Temple V, and I have spent more years than I’d like to admit studying their writings and their painted narratives in order to reconstruct the details of this vibrant, ancient culture whose poetry and time-keeping rival Homer and Archimedes. On December 21, pull back the curtain and see the Maya for who they were and who they continue to be.

Victoria Lyall, Associate Curator, Art of the Ancient Americas