During the making of Full Metal Jacket, actor Matthew Modine kept a diary and took numerous photos on set. In 2005 it was published as a book, Full Metal Jacket Diary, now out of print. Modine has since developed the diary into an innovative app—or “app-umentary”—for the iPad (available from iTunes). Unframed’s Scott Tennent caught up with Modine inside the Stanley Kubrick exhibition to talk about the making of the movie, the book, and the app.

[vimeo http://vimeo.com/43685430]

Scott Tennent: How did you get the part for Full Metal Jacket?

Matthew Modine: It’s a funny story. I was with a good friend of mine, David Alan Grier; we were having pancakes at a place on Sunset Boulevard called the Source, and over David’s shoulder there was a guy looking at me, giving me the hairy eyeball. David looks over and says “Oh, that’s Val Kilmer, he’s a really nice guy,” [and] he introduced me. Val says “Yeah, I know who you are. I’m sick of you.” I had been on this run of films—Birdy, Mrs. Soffel, and Vision Quest. And Val says, "Now you’re doing Kubrick’s film.” When we finished our breakfast I called my manager. He didn’t know anything about it. I knew [Kubrick] was making a film with Warner Bros., so we asked [director] Harold Becker to send a print of Vision Quest, and we asked Alan Parker to send some dailies from Birdy. It turns out that maybe Stanley didn’t know anything about me and Val Kilmer might have been responsible for me getting the part in Full Metal Jacket.

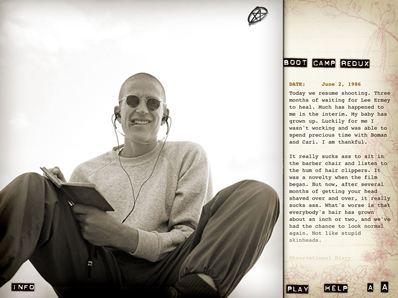

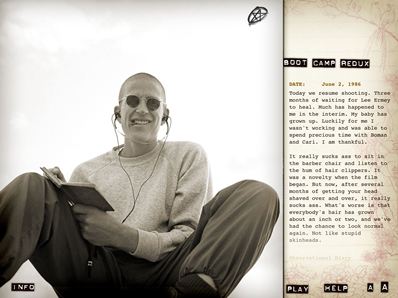

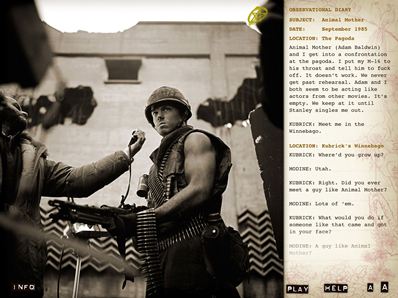

Screenshot from Full Metal Jacket Diary

Screenshot from Full Metal Jacket Diary

ST: What was your first meeting with Kubrick like?

MM: [Once my wife and I settled in London,] Stanley sent his driver to take us to his home out in the countryside. We drove to this amazing gatehouse and this long driveway that went on forever until we arrived at this beautiful old country estate. The dogs came running out, and then this friendly looking guy with a beard, shabby clothes, and tousled hair came out of the house. He was just as kind and sweet as you could imagine—which was quite different than everything that was being told to me about his personality. He was a good friend, a loving father figure, and a great mentor—that was my relationship to Stanley.

ST: And on set, he didn’t transform into the version of Stanley Kubrick you’d been warned about?

MM: I saw that he had the ability to be quite cruel. But I don’t think that it was unfounded cruelty. He couldn’t suffer fools or stupidity. That’s not to say that he wasn’t empathetic; he had tremendous empathy.

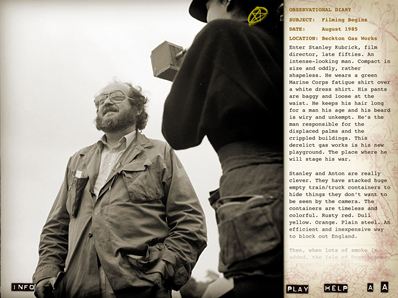

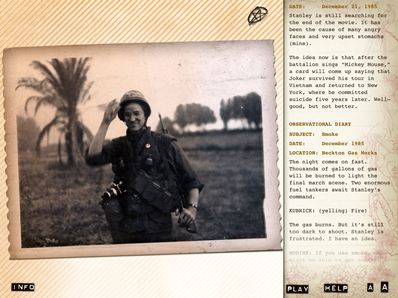

Screenshot from Full Metal Jacket Diary

Screenshot from Full Metal Jacket Diary

ST: You can read his films as having an extreme sensitivity.

MM: I agree with you completely. He’s often accused of being cold or inhuman, that his films have such a hard veneer. I don’t think that’s the case at all. What Stanley Kubrick did, perhaps better than any filmmaker, was take an honest look at human beings. Generally Hollywood films create an idealistic reflection of the goodness of human beings—solving problems through heroes. But the fact of the matter is, unless we look at each other honestly and see not what we hope to look like, but who and what we are, what we’re capable of, what we’ve done to each other in order to achieve success—unless you’re conscious of those things, you’re destined to repeat those mistakes.

ST: How did Kubrick, on set, relate to you as director-to-actor, as opposed to person-to-person?

MM: I think it was the idea of repetition—to get [away] from conscious choices or from posing. We’ve all grown up watching movies, so sometimes we base our characters on those we’ve seen in movies. What Stanley was interested in was who I am. I grew up in Utah, my dad was a drive-in theater manager—which was a completely alien world to Stanley, having grown up in the Bronx. That was fascinating to him. Through repetition, he’s peeling away the layers of an onion to get to the core of who Matthew Modine is. Not who Matthew Modine imagines Private Joker is, not a reproduction of John Wayne or Jimmy Stewart or Henry Fonda.

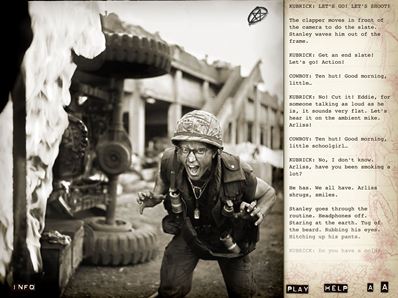

ST: How did you, in the moment, handle all that repetition?

MM: I was comfortable with it because it was Stanley Kubrick. I knew enough of the history of his films that if he wanted to do it again there must be some reason. It was maddening sometimes to try to understand why—how could I do it differently? But understanding wasn’t important for me. It was to try to do it and get it right.

Screenshot from Full Metal Jacket Diary

Screenshot from Full Metal Jacket Diary

ST: All told, you were in London shooting Full Metal Jacket for two years. During that time, your son was born—a memory I’m sure you’ll forever tie to the making of this film.

MM: We found out that [my wife] was going to have an emergency Cesarean. The baby wasn’t growing right in the womb. She was very early, seven months. I knew I couldn’t just not show up for work. When they picked me up [to bring me to the set], I knew I wasn’t going to work that day—they were shooting Dorian Harewood [who played Eightball]. I wasn’t involved in that scene. So I raced to work and Stanley didn’t show up on time. It was seven o’clock, eight o’clock, nine o’clock. I was freaking out. He finally showed up for work and I told him the situation. He said “What are you going to do? Are you going to stand in the operating room? You’ll faint as soon as they cut her open! You’ll see all that blood and you’ll pass out. You’re just going to be in the way of the doctors.”

I said, “No, I have to go. I have to be there with my wife.” And he started telling me all these really practical reasons why I didn’t need to be there. I had a pocket knife with me; I put it in my palm and I said “Look, I’m going to cut my hand open and I’m going to have to go to the hospital, or you can let me go to the hospital to be with my wife.” He moved away from me and he said “Okay, but come back immediately after it’s done.”

I think what pissed him off was that I told him that I wasn’t going to work. I was assuming the director’s role—“don’t tell me what I’m going to do or what I’m going to need.” I came back and I handed out cigars. I didn’t film for three more days.

And then he gave me a hard time about my son’s name. His name is Boman. It never occurred to me [that Bowman was the name of the main character in 2001]. Five years before he was born we had decided to name him Boman Modine. It wasn’t until I got home and was watching 2001 and I realized he thought I was naming my son after Keir Dullea.

Screenshot from Full Metal Jacket Diary

Screenshot from Full Metal Jacket Diary

ST: The Full Metal Jacket Diary app is a really terrific look into the making of this film. Did you keep similar diaries on all of your movies?

MM: No. It was because I was playing a journalist. I found this little Asian notepad as a prop. I thought, I’m playing a journalist, so this would be a good thing for me to write in. A friend of mine gave me a Rolleiflex camera before I left—it was a twin-lens reflex camera, a really beautiful piece of art. I found myself in a situation where Stanley Kubrick was going to allow me to take pictures on his set. Playing a journalist and keeping the diary, I suddenly, without premeditation, found myself with this kind of amazing document. Stanley encouraged me to keep a diary, asked me to read my diary on set sometimes—which was a really good thing, by accident. It forced me to be more observant, to take better notes about what was happening.

The thing that I love about the diary now, in 2013, is that it is a time capsule of that moment—making a film with Stanley Kubrick—but it’s told from the perspective of a young man in a situation that he doesn’t understand. It’s not written in hindsight, it’s written in the moment—full of vulnerability and naiveté.

ST: What didn’t you understand?

MM: You’re asked to star in a Stanley Kubrick film. You’re supposed to start filming. A month goes by, two months go by, there’s a delay. You don’t know what the delay is. Then you start filming and you film this scene and it’s not working. You start to think, because of your ego, that you’re somehow responsible for the lack of progress. You don’t take into consideration that Stanley is trying to find his movie; that he’s trying to discover the truth of the moment he’s trying to capture on film. The light looks like London, gray and overcast, when you’re supposed to be in Vietnam; the set’s not really ready; you’re not really understanding what this scene is about. He’s scrambling three or four different places as he tries to find his film. What you discover in the diary is the idea of being. The great struggle in life, and as an artist particularly, is to be. Some people discover it earlier than others. I think Marlon Brando discovered it early. Picasso. Mozart. They’re not trying to please somebody else; they discover their genius and they are. Stanley was someone who understood himself very early.

I was out in a field feeling completely lost, feeling that I’m failing Stanley, that he’s not making forward progress—based on my experience on other films, knowing what a shooting schedule is like and how much work you have to accomplish each day to get the call sheet and accomplish the next day’s work. Here we were months into filming and the call sheets meant nothing. We weren’t making any forward progress and my ego is telling me that this is my fault. I’m failing somehow; I’m not giving him what he needs. I was standing out in a field and I saw Stanley driving up in a jeep and he turned and started coming toward me. I tried to hide in the tall grass but he comes up and sees that I’m troubled. He asked what was the matter and I said “I feel like I don’t know how to play this role. I don’t know what you want.”

He turned off his jeep, pulled on his beard, cleared his throat, and said “Listen, I don’t want you to ‘play’ anything; I just want you to be yourself.” He drove away and I wrote in my diary, “I know the important part of that sentence was to be.” That was a young man who wrote that. Like I said before about the process of peeling away, of repetition; you start to get to the DNA of a person. The false façade, the showing off… it’s a journey. It’s not an easy thing to arrive at.

Screenshot from Full Metal Jacket Diary

Screenshot from Full Metal Jacket Diary

ST: When did it occur to you to turn the journal into something to share?

MM: I always loved the photographs and I wanted to publish the photographs. That’s all I wanted to do. I finally found a small publishing company called Rugged Land to make something extraordinary. It had to be something that Stanley would hold and say “This is awesome.” That’s why it was a metal book with a hinge, limited to 20,000 pieces. [The publisher] said “It’s not going to be enough just publishing the photographs, you’re going to have to tell a story.” Once we transcribed the diary, we realized this was an amazing journey into the world of Stanley Kubrick. And it was an innocent perspective, an unguarded journey.

ST: How and why did it transition into an app?

MM: The [book version] was limited, and when it sold out Adam Rackoff [who had previously worked at Apple] approached me and asked how I’d feel about turning the book into an app—something interactive, deeply immersive. We’d create a score, add sound effects, I’d do the narration, and we’d use high-res scans of all the negatives. He wanted to make something Stanley Kubrick would be proud of—so I knew Adam’s heart was in the right place.

ST: It really is immersive—it’s like an interactive documentary.

MM: That’s the fun thing about an app. With a book, it’s published and that’s it. With an app, it can continue to grow and develop. There will be updates coming out with more photographs taken by other actors, to be able to share their perspective on certain things—different angles on the same situation. And I’ve interviewed other people. I’m calling it “Full Metal Roshamon.”

You can download the Full Metal Jacket Diary, as well as LACMA’s Stanley Kubrick app, from iTunes.