Ming Masterpieces from the Shanghai Museum, on view now through June 2, presents ten masterpieces of Ming dynasty (1368–1644) painting. Five of the artists were court painters in the Forbidden City (the imperial palace) in Beijing, while the other five were gifted Ming professional painters whose works were stylistically and thematically related to those of the leading court masters.

These paintings represent a type rarely seen in American museum collections, where the prevailing taste in collecting over much of the past century has been for literati (scholar or wenren) paintings. This exhibition explores the role of imperial patronage of Ming dynasty painters, the uses of paintings as political propaganda, Daoist themes of transcendence, and the revival of antique Song dynasty (eleventh through the thirteenth centuries) painting styles in the early Ming period.

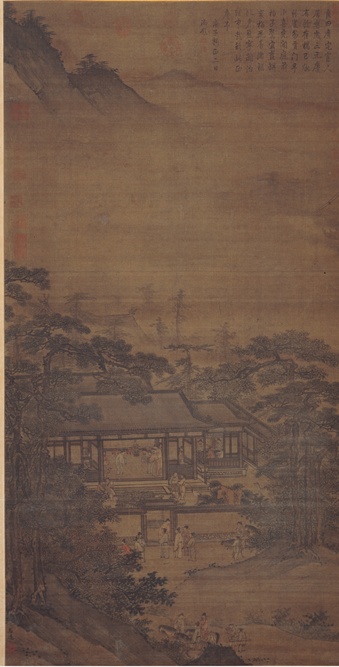

Wu Shi’en, Gazing over Lin Lake in the Evening, Ming dynasty, early 16th century, Shanghai Museum

Wu Shi’en, Gazing over Lin Lake in the Evening, Ming dynasty, early 16th century, Shanghai Museum

The fifth Ming emperor, Xuanzong (reign title Xuande, r. 1426–1435) created an imperial painting academy in the Forbidden City on the model of the great academy that existed at the Southern Song dynasty court in the thirteenth century. The loosely constructed Ming academy—in which court painters were given the same ranks and titles as officers of the imperial secret service—flourished into the early sixteenth century. Painting played a key role at the imperial court, most often to emphasize the ruler’s moral integrity, or as examples of upright behavior for those serving in government. Narrative and symbolic images by professional artists outside the court played similar roles throughout Chinese society. A wide range of paintings is represented here, including depictions of Daoist mythology (strange tales of immortal beings), genre scenes, landscapes, and bird-and-flower paintings.

The works by court painters in the exhibition cover a broad range of styles and subjects. Court painters created both secular and religious images, and paintings at court had many functions in the social, spiritual, and political realms. Images from ancient narratives projected idealized modes of human behavior, especially for the ministers and high-ranking court bureaucrats who worked in the palace and who had daily engagement with the emperor. Court paintings were also a mirror of the emperor’s own persona and his goals for the empire and its governance. The court painter Zhou Wenjing’s New Year’s Day is a good example of a work that projects a vision of an orderly society celebrating the most auspicious moment in the annual time cycle; the painting is a mirror of the consequences of good government. Zhou Wenjing, a native of Fujian province along China’s southeast coast, worked at the imperial court for nearly forty years.

Zhou Wenjing, New Year's Day, Ming dynasty, 15th century, Shanghai Museum

Zhou Wenjing, New Year's Day, Ming dynasty, 15th century, Shanghai Museum

Another early Ming court master was Li Zai, who was a native of Guangdong (Canton) in the far south and worked in the Forbidden City in the early fifteenth century. Li was known for both landscape and figure paintings. His masterpiece The Daoist Adept Qin Gao Riding a Carp is over five feet tall and is one of several Daoist paintings in the exhibition (others are by An Zhengwen, Wang Zhao, and Zhang Lu). The painting depicts a fully “realized” (spiritually emancipated) Daoist adept bidding farewell to his disciples as he prepares to transcend the boundaries of existence. Daoist adepts like Qin moved beyond yin and yang, time and space, and life and death. The immortals (xian) were revered as powerful spirits by aristocrats and commoners alike. They were (and still are) worshipped in Daoist temples and shrines throughout China. They are believed to have achieved union with the Dao (Tao), an empty void that paradoxically and spontaneously generates qi, the vital energy of which all things are made. Moving between dimensions, they are well situated to perform miracles.

Li Zai, The Daoist Adept Qin Gao Riding a Carp, Ming dynasty, 15th century, Shanghai Museum

Li Zai, The Daoist Adept Qin Gao Riding a Carp, Ming dynasty, 15th century, Shanghai Museum

An example of the astonishing range of Daoist imagery in Chinese painting is reflected in the sixteenth-century painter Zhang Lu’s album of eighteen leaves. The paintings, in ink and light colors on gold-flecked paper, depict the cosmic forces of yin and yang and a host of deities and immortals, including the God of Longevity, the Five Phases, and several of the Eight Immortals (including the leader Zhongli Quan and his student Lü Dongbin, patron saint of poets, swordsmen, alchemists, and manufacturers of wine and ink).

The type of Ming professional and court paintings presented here has only recently been recognized as one of the most popular types of Ming dynasty painting. LACMA is honored and excited to partner with the Shanghai Museum in this rare exhibition. We are especially grateful to Beijing Xia Jingshan Culture Development Ltd. and the American Friends of the Shanghai Museum for helping bring this project to realization.

Stephen Little, Curator and Department Head, Chinese and Korean Art