This Sunday, LACMA celebrates Earth Day with a day full of tours, art-making workshops, music, and more. The first Earth Day on April 22, 1970, marked the birth of the modern environmental movement. Designed to be a teach-in about conservation and environmental issues, it tapped into the grassroots movements driving many of the anti-war protests and groups. Earth Day 1970 brought issues of pollution, conservation, deforestation, and endangered species into a broader public consciousness. To commemorate this event, Robert Rauschenberg made a lithograph and collage at the Los Angeles printshop Gemini G.E.L. (edition 50) and an offset poster with nearly the same composition to benefit the American Environment Foundation (edition 300 signed, 10,000 unsigned). This was the first time the artist had used a mass-produced poster to express social concerns; however, this was not the first time he had expressed concerns about the state of the environment in his art, and he maintained his interest in this issue until his death in 2008.

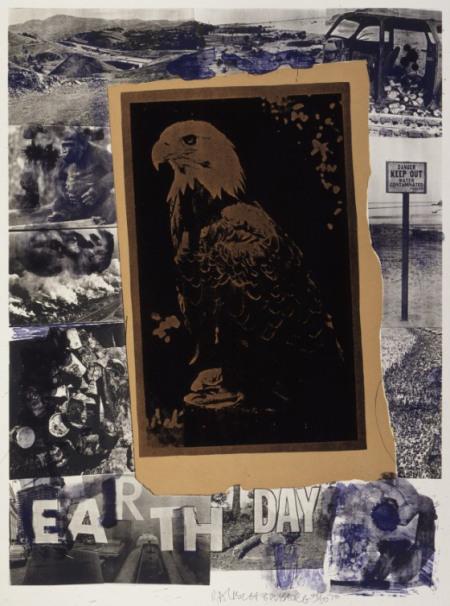

Earth Day, Robert Rauschenberg, Gemini G.E.L., United States, 1970

Earth Day, Robert Rauschenberg, Gemini G.E.L., United States, 1970Gift of the Sidney and Diana Avery Trust

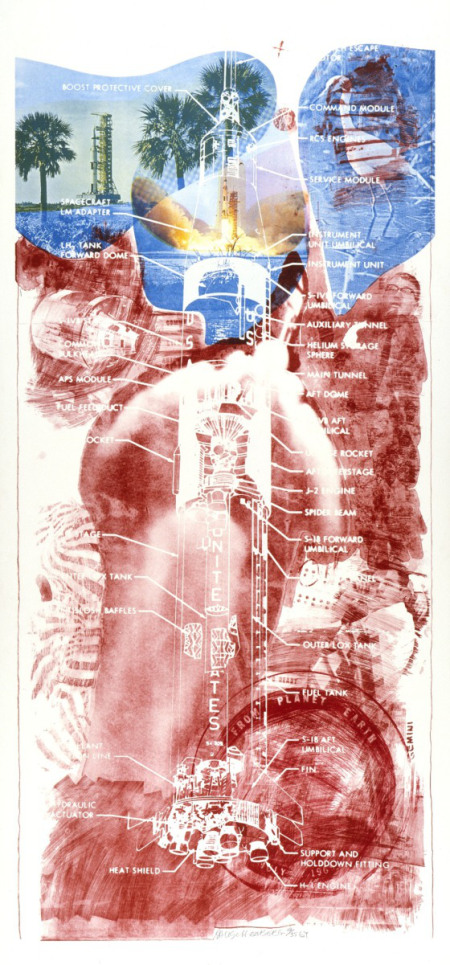

Rauschenberg’s earlier, more oblique, expressions of environmental concerns were based upon his personal observations of humankind’s impact on the earth. Rauschenberg grew up in Port Arthur, TX, an oil refinery town on the Gulf of Mexico. His early memories of the oil derricks belching foul air may have inspired his vision the capital of Hell, Dis, in his illustrations of Dante’s Inferno (1959-60). In 1969, Rauschenberg made a series of prints in response to his viewing of the Apollo 11 lunar launch at the Kennedy Space Center. In his journal recalling the event, he wrote, “The incredibly bright lights, the moon coming up, seeing the rocket turn into pure ice, its stripes and USA marking disappearing—and all you could hear were frogs and alligators.” His interest in striking a balance between technology and nature is reflected in the print Sky Garden (1969) currently on view in the Stanley Kubrick exhibition. Although the main image in the monumental lithograph is the Saturn V rocket, the top register features palm trees and a heron.

Sky Garden, Series: Stoned Moon, Robert Rauschenberg, United States, 1969, Gift of Drs. Katherina and Judd Marmor in honor of the museum's twenty-fifth anniversary

Sky Garden, Series: Stoned Moon, Robert Rauschenberg, United States, 1969, Gift of Drs. Katherina and Judd Marmor in honor of the museum's twenty-fifth anniversary

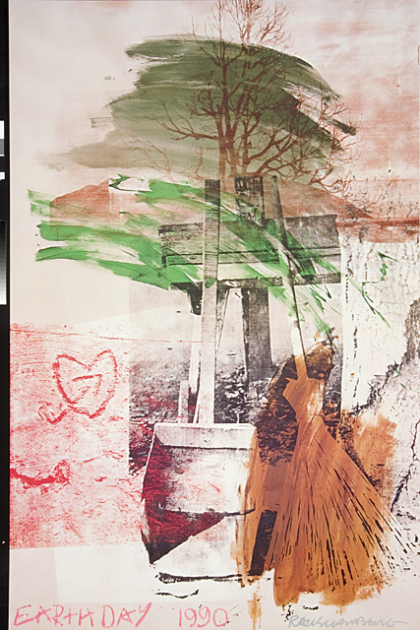

His message became more explicit in the poster and print from 1970. Pictures—culled from newspapers and magazines—of crowded highways, deforested land, strip mining, piles of garbage, polluting factories, and an endangered gorilla surround the central image of the bald eagle, the symbol of the United States threatened with extinction because of pesticides. Twenty years after the original event, Earth Day 1990 was dedicated to expanding the message of environmental protection internationally and emphasizing the importance of recycling. In the lithograph, Earth Day 1990 (edition 75), published by Gemini to benefit the Earth Day 1990 organization, Rauschenberg took a less polemical approach than he had in 1970. Using photographs he shot himself, he placed a stand of denuded trees at the top of the composition, while the right and left registers contain close-up images of bark, one marred by graffiti. He then applied ink in tones of green and raw sienna over the pinkish-brown printed images in the background.

Earth Day 1990, Robert Rauschenberg, United States, 1990, Partial and promised gift of the Grinstein Family

Earth Day 1990, Robert Rauschenberg, United States, 1990, Partial and promised gift of the Grinstein Family

In Earth Day 1990, Rauschenberg addresses the issue of personal responsibility. The dustpan and broom in the center of the print seem to call on each of us individually to clean up the mess we have made. In 1991, when Rauschenberg revealed his project for Earth Summit ’92 The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (a result of the international activities of Earth Day 1990), he directly stated his point of view that, “once the individual has changed, the world can change.” Deeply concerned about the environment, Rauschenberg used his artistic ability to support organizations financially and impart powerful messages.

Sienna Brown, Wallis Annenberg Curatorial Fellow, Prints and Drawings