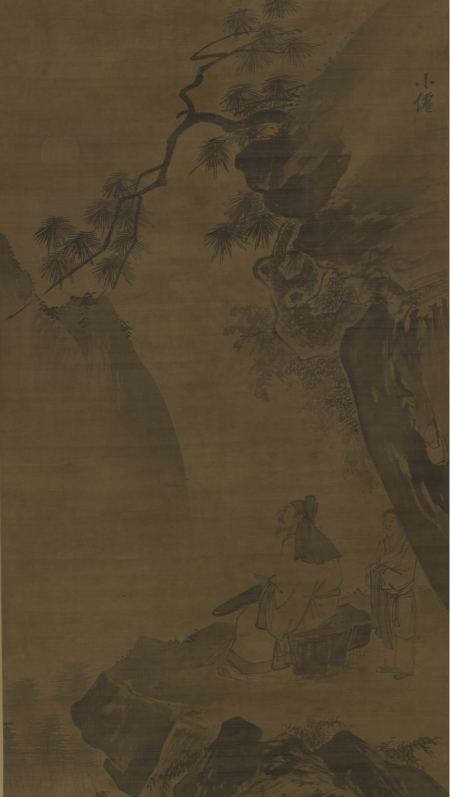

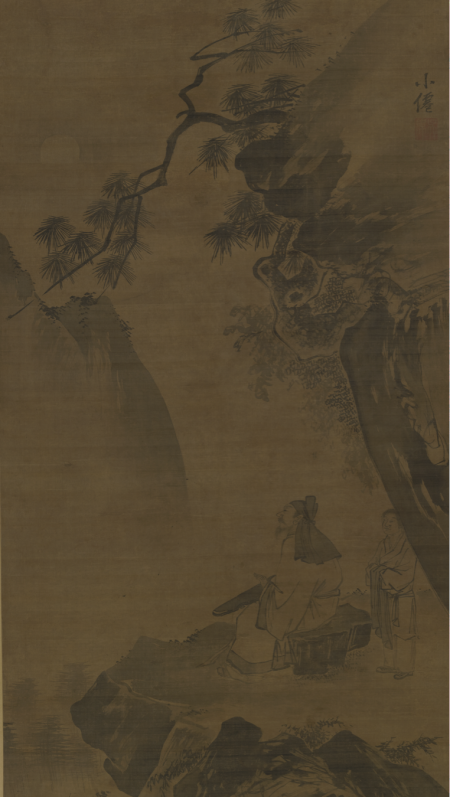

Wu Wei (1459–1509) is featured in Ming Masterpieces from the Shanghai Museum at LACMA by the hanging scroll titled Playing the Zither in a Pine Valley. Like virtually all of Wu Wei’s paintings, it is undated, but is a fine example of the style of Wu Wei, as the painting combines landscape and portraiture—two areas of painting in which he excelled.

Wu Wei, Playing the Zither in a Pine Valley, fifteenth to early sixteenth centuries, Shanghai Museum

Wu Wei, Playing the Zither in a Pine Valley, fifteenth to early sixteenth centuries, Shanghai Museum

Wu Wei was a professional painter who worked both in and out of the Imperial Court. In fact, he worked at the Imperial Court several times for several Emperors of the Ming Dynasty, having at times withdrawn voluntarily and at times being handed the pink slip by bureaucrats who disliked Wu because of his disdain for “important people.” This may have been due to his background, having come from a literati family that fell on hard times during his childhood. This caused his training to abruptly stop. However, he was a lucky man who attracted the patronage of a wealthy duke in Nanjing that launched his career as a professional painter.

Wu also had a difficult time adapting to the highly regimented life of the Court. He was a heavy drinker and often showed its effects in rude and unseemly behavior. In fact, it is thought that his drinking led to his fairly early death, just as he was about to embark on yet another summons by the Court. However, when he was at his best as a painter, he was very good indeed. The Emperor Xiaozong (the Hongzhi Emperor) gave Wu a seal that read “First Among Painters” (hua zhuangyuan). Now that’s a Good Housekeeping seal of approval!

Wu painted both landscapes and figures. Some of his figure paintings depict a meticulousness and exactitude that show off his fine technique. In others, he painted with a “wild brush,” using sweeping and zigzagging strokes in varying pressures to create a highly dynamic quality. In landscapes, he generally favors the dramatic, employing bold brushwork to reflect mountainsides and flora.

Wu Wei, Playing the Zither in a Pine Valley (detail), fifteenth to early sixteenth centuries, Shanghai Museum

Wu Wei, Playing the Zither in a Pine Valley (detail), fifteenth to early sixteenth centuries, Shanghai Museum

The Wu Wei in LACMA’s exhibition is a good example of much of his painting style. The landscape around the figure is full of aggressive brushwork that does not depict the rockery and trees as much as it evokes their craggy, gnarled, and wild attributes. On the other hand, the figures are really a blend of his meticulous and delicate style in the rendering of the features and a hint of his more aggressive style in the drapery of the garments. These painting styles were to have a profound influence on many other painters in the early and mid-Ming period (the so-calling Jiangxia school), and equally but later led to criticism by luminaries like Dong Qichang in the late Ming, who criticized his paintings for their lack of delicacy and restraint. Thus the very practices that made Wu Wei famous in his own day were the reasons why the late Ming scholars (and virtually all that followed them up to the twentieth century) castigated his paintings. Only in the last few decades has our bias in favor of literati styles of Chinese painting made room for Wu Wei, other professionals, and Court painters of the early Ming in the pantheon of respected Chinese painters.

Franklin Tom, East Asian Art Council member