At a recent event I had the chance to sit next to actor Cheech Marin. We talked about his collecting of Chicano art, the enduring struggles of Latino artists to gain recognition, and the persistent need to classify and categorize artists who are traditionally not considered part of the mainstream. One anecdote particularly stayed with me: he related how when John Valadez was once asked if he considered himself a Chicano artist, he wryly retorted, “Only if it bothers you.” This, I thought, is much more than an exacting punch line.

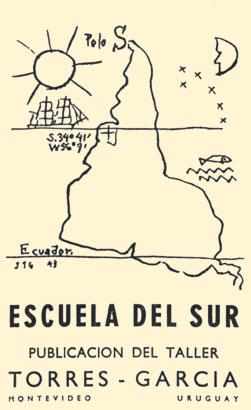

1943 drawing by Joaquín Torres García, illustrated in the cover of the Escuela del Sur (Montevideo: El Taller Torres García, 1958)

1943 drawing by Joaquín Torres García, illustrated in the cover of the Escuela del Sur (Montevideo: El Taller Torres García, 1958)

As a curator and scholar of Latin American art, I often think about how best to present Latin American art within an institutional context. The center-periphery discussion is nothing new in our discipline. Every art historian of Latin American art is familiar with Joaquín Torres García’s iconic inverted map: a proto-conceptual attempt to reverse hierarchies and position the South (perceived to be in the edges of the art world) as the North (the center of artistic innovation).

Wifredo Lam, The Jungle, 1943, gouache on paper mounted on canvas, Museum of Modern Art, New York

Wifredo Lam, The Jungle, 1943, gouache on paper mounted on canvas, Museum of Modern Art, New York

We are also aware of how MoMA once used to display Wifredo Lam’s iconic The Jungle, now considered a masterpiece of modernism, on a wall next to the coatroom. Although the perception of the field has grown in leaps and bounds over the last decade or so, how we present Latin American art in an encyclopedic museum remains contested territory.

Installation of the ancient art galleries at LACMA; casework designed by Jorge Pardo

Installation of the ancient art galleries at LACMA; casework designed by Jorge Pardo

At LACMA, for example, we devoted an entire floor (Art of the Americas building) to Latin America for the first time in 2008. One half of the floor, designed by the artist Jorge Pardo, encases our world-class collection of pre-Columbian art. The other half of the floor is devoted to our expanding collections of Spanish colonial, modern, and contemporary art.

Installation of the Spanish colonial art galleries at LACMA

Installation of the Spanish colonial art galleries at LACMA

A fair question (and one that does not go unasked), is why divide the material geographically? Shouldn’t modern Latin American art be included in the modern art galleries and contemporary Latin American art in our contemporary art building (BCAM)? What about Spanish colonial art? Does it belong in the European or American art galleries?

These questions, as useful as they are, are also telling of the liminal position that the field continues to occupy within encyclopedic museums and the art historical canon in general. I am always puzzled as to why the question does not get much asked for other fields, say Islamic, Japanese or Indian art—though I am not implying that these areas, as well as others, have not undergone vicissitudes of their own.

To be sure, most of us have an innate impulse to classify the chaos that surrounds us, to create neat packages of information that are easy to manage and engender “meaning.” Sometimes these categories stick for years. But despite our best efforts, the process is impossible to fix and the resulting narratives we devise are always subject to revision. In other words, there are many ways to tell a story, and there are many stories to tell.

Julio Le Parc, Mural: Virtual Circles, 1964-1966, wood, aluminum, stainless steel, and polished metal, purchased with funds provided by Debbie and Mark Attanasio, Jane and Marc Nathanson, Jane and Terry Semel, The Loreen Arbus Foundation, Janet Dreisen Rappaport and Herb Rappaport, an anonymous donor, Alyce Woodward Oppenheimer, and the Bernard and Edith Lewin Collection of Mexican Art Deaccession Fund through the 2013 Collectors Committee

Julio Le Parc, Mural: Virtual Circles, 1964-1966, wood, aluminum, stainless steel, and polished metal, purchased with funds provided by Debbie and Mark Attanasio, Jane and Marc Nathanson, Jane and Terry Semel, The Loreen Arbus Foundation, Janet Dreisen Rappaport and Herb Rappaport, an anonymous donor, Alyce Woodward Oppenheimer, and the Bernard and Edith Lewin Collection of Mexican Art Deaccession Fund through the 2013 Collectors Committee

Having galleries devoted specifically to Latin American art tells one story. Broadly, it does two things: it calls attention to the cultural achievements of the region across a broad stretch of time and geography. It also emphasizes the theme of “locality.” Let us consider, for example, our recent acquisition of Julio Le Parc’s Mural: Virtual Circles, an iconic op art work by an Argentinean-born artist who has lived and worked most of his life in France. In our current galleries, the work is displayed alongside others by abstract artists active in South America (e.g., Jesús Rafael Soto, Sérgio de Camargo, and Raúl Lozza). Together, they show that artists from Latin America were key players in the development of abstractionism and kinetic art internationally. This is especially significant because for a very long time Latin American art was—and to an extent still is—equated with the “picturesque” and the likes of Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, and cohort.

Diego Rivera, Mexico, 1886–1957, Still Life with Bread and Fruit, 1917, oil on canvas, Gift of Morton D. May

Diego Rivera, Mexico, 1886–1957, Still Life with Bread and Fruit, 1917, oil on canvas, Gift of Morton D. May

Some may rightly argue that Le Parc’s work therefore best belongs in the modern European galleries, as do many other works in the collection—including Rivera’s cubist painting Still Life with Bread and Fruit. And surely, when asked, many artists would prefer not to be categorized according to the nationality noted in their passport. But here is the thing: context is important and does inform an artist’s work. In the case of Le Parc, it is instructive to remember that throughout his life he maintained one foot in Latin America, where he frequently traveled and exhibited his work. And when he went on to win, with great fanfare, first prize at the 1966 Venice Biennial, he represented Argentina, not France! Is Mural: Virtual Circles therefore the work of an artist from Argentina, Europe, or both? The question of where best to display the work and what context is more “appropriate” can be mystifying—and at the end of the day the decision is entirely subjective and made by those who at the moment can (i.e., museum professionals and scholars).

I am not espousing one view, or stating that having galleries devoted to Latin American art is the model to follow. Geographically-based galleries can be rather constricting and marginalizing. What I would like to suggest, instead, is that by moving towards erasing all borders, establishing a totalizing and “international” global narrative, we also need to consider that we are in danger of sacrificing other contexts that can be equally meaningful. By the same token, the limitation of defining artists by strict geographic parameters is patent. So what to do?

In the ideal museum (and nowadays this is a much talked about topic in reference to LACMA), we could perhaps think of devising contiguous spaces. Think of turning Torres García’s upside down map sideways and extending it across the globe. These areas—nodal points—could intersect and retain some specificity that would allow for the creation of various and simultaneous narratives. The idea would be, for example, to have galleries devoted to early modern art (16th–18th centuries) and modern art that would be more all-encompassing and include works from regions beyond Europe, but without presenting them as a footnote or afterthought. In other words, the works could be displayed together and separate.

This way the art produced by Latin American artists—particularly after the Conquest—could be presented in manners that emphasize (instead of hinder) connections and a multiplicity of contexts. It is not about “shaking up the box” and “mixing and matching”—it is about devising thoughtful adjacencies that would allow the art to “speak” on many levels (including aesthetic), and emphasize local, European, African, and Asian cultural traditions that informed the creative output of the region. After all “globalism” is nothing new. There were always networks of exchanges and vectors of transmission that inextricably linked cultures together.

By rethinking the politics of displaying Latin America art, which still sits so uncomfortably between categories (local vs. international; high art vs. low art; original vs. derivative), perhaps we could also question the so-called more canonical areas of museum and academic art discourse. In the end, as the artist John Valadez astutely implied when pressed to define his “artistic lineage”—art is about much more than genealogical fabrications.

Ilona Katzew, Curator and Department Head, Latin American Art