Two major exhibitions at LACMA this fall touch upon the theme of Art+Film: Under the Mexican Sky: Gabriel Figueroa—Art and Film and Agnès Varda in Californialand (opens Sunday, November 3). A third, Masterworks of Expressionist Cinema: “The Golem” and Its Avatars, looks closely at the legend of the golem as it is represented in film, art, and popular culture. Today's Unframed expands upon yesterday's post, as curators Timothy Benson, Rita Gonzalez, and Britt Salvesen talk with Unframed's Scott Tennent about the current exhibitions that bind art and film.

Scott Tennent: Rita and Britt, you co-curated Under the Mexican Sky: Gabriel Figueroa—Art and Film, which is currently on view. Figueroa was a celebrated cinematographer in Mexico who worked from the 1920s to the 1980s. How did you use the context of an art museum to present his work?

Gabriel Figueroa, Film still from Enemigos, directed by Chano Urueta, 1933, © Gabriel Figueroa Flores Archive

Gabriel Figueroa, Film still from Enemigos, directed by Chano Urueta, 1933, © Gabriel Figueroa Flores Archive

Rita Gonzalez: Britt and I were really interested in how we could present Figueroa to an audience that might have more familiarity with Mexican art. They’re more accustomed to the muralists, the great modernist painters, and photographers of Mexico. We really wanted to situate Figueroa’s aesthetics and technical accomplishments in relationship to that art lineage. Figueroa knew artists like Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, and was part of those circles. In fact Rivera referred to Figueroa as “the fourth muralist” alongside that group.

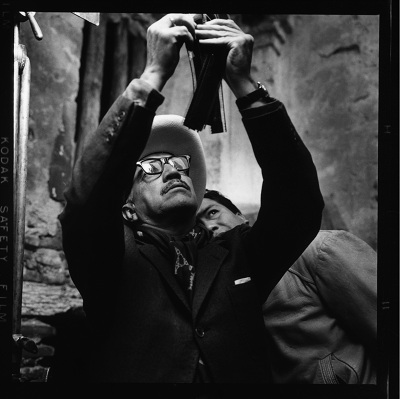

Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Gabriel Figueroa reviewing light tests for the film Sonatas, directed by Juan Antonio Bardem, 1959, Gabriel Figueroa Flores Archive, © Estate of Manuel Álvarez Bravo

Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Gabriel Figueroa reviewing light tests for the film Sonatas, directed by Juan Antonio Bardem, 1959, Gabriel Figueroa Flores Archive, © Estate of Manuel Álvarez Bravo

Britt Salvesen: And they influenced each other mutually. Although this exhibition has one person’s name on it, and it’s his story we tell throughout, it’s also a story of creative networks. It’s a challenge to think of how to present the art of cinematography in an art museum. When someone like Figueroa emerges with a really strong vision, that’s a story we want to tell—but in the medium of narrative film that vision also has to be linked to the vision of a director, which is also quite strong.

Ángel Corona Villa, film still from Dias de otoño, directed by Robert Gavaldón, 1962, © Gabriel Figueroa Flores Archive

Ángel Corona Villa, film still from Dias de otoño, directed by Robert Gavaldón, 1962, © Gabriel Figueroa Flores Archive

Tennent: Seeing the list of people Figueroa worked with—directors as disparate as John Huston and Luis Buñuel—says something interesting about Figueroa.

Salvesen: Sometimes Figueroa’s vision was aligned with his director’s, and sometimes they were at odds. Figueroa and Emilio Fernández were really in sync, each pushing the other to really vivid iconography of the legacy of the Mexican Revolution, among other things. When Figueroa worked with Luis Buñuel, they had a bit of disparity in their viewpoints—Buñuel not being interested in this monumentalized version of Mexico and wanting something grittier, more ambivalent, surreal. Yet both collaborations produced numerous films. So in some cases the tension was productive.

Ángel Corona Villa, Pedro Armendáriz in a still from the film La escondida, directed by Robert Gavaldón, 1955, © Televisa Foundation

Ángel Corona Villa, Pedro Armendáriz in a still from the film La escondida, directed by Robert Gavaldón, 1955, © Televisa Foundation

Tennent: Britt, Gabriel Figueroa is one of two exhibitions you’re co-organizing this fall. The other, with Tim, is Masterworks of Expressionist Cinema: “The Golem” and Its Avatars. Can you elaborate on that title?

Salvesen: The tale of the golem is a folk tale set in medieval Prague, when Jewish residents were being persecuted by a Christian ruler. To defend themselves, a rabbi created a figure out of clay and, using incantations and spells, animated that figure. It then rampaged through the city to protect the Jews from persecution.

You can imagine any number of variations on that tale. It’s also a great metaphor for the act of artistic creation.

Tennent: So you’re taking that figure and showing it across cultures and eras?

Paul Wegener (director), Germany, 1874–1948, Carl Boese (director) Germany, 1887–1958, Film still from Der Golem: Wie er in die Welt kam (The Golem: How He Came into the World), 1920, written by Paul Wegener and Henrik Galeen, produced by Paul Wegener, B&W, silent

Paul Wegener (director), Germany, 1874–1948, Carl Boese (director) Germany, 1887–1958, Film still from Der Golem: Wie er in die Welt kam (The Golem: How He Came into the World), 1920, written by Paul Wegener and Henrik Galeen, produced by Paul Wegener, B&W, silent

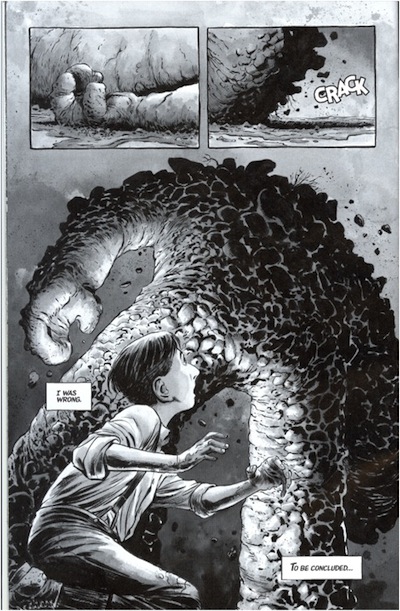

Timothy Benson: All the way up to contemporary comic books. The film The Golem, from 1920, is by director Paul Wegener, who is very devoted to this story line—this is the third of three films he made on the subject. And he plays the golem. It’s an incredible immersion. That figure, the way it’s styled and costumed, has appeared again and again in artistic and popular culture since then—including The Simpsons.

Tennent: This is your second Masterworks of Expressionist Cinema exhibition, following last year’s on the films Metropolis and Dr. Caligari. Will there be more in the series?

Salvesen: Next fall we have planned a much larger show about German Expressionist cinema, which is coming to us from the collection of the Cinémathèque Français but can be augmented with holdings of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, since many of the émigrés from the German Expressionist era ended up in Hollywood. That will be a chance to make connections to film noir and contemporary cinema. Everyone from Tim Burton to David Lynch to Guillermo del Toro cite this influence.

Dave Wachter (illustrator), United States, born 1975, Steve Niles (writer), United States, born 1965, Matt Santoro (writer), United Stated, born 1976, Page from Breath of Bones: A Tale of the Golem, no. 2 (July 2013), private collection, Los Angeles, © 2013 Steve Niles, Matt Santoro, and Dave Wachter

Dave Wachter (illustrator), United States, born 1975, Steve Niles (writer), United States, born 1965, Matt Santoro (writer), United Stated, born 1976, Page from Breath of Bones: A Tale of the Golem, no. 2 (July 2013), private collection, Los Angeles, © 2013 Steve Niles, Matt Santoro, and Dave Wachter

Tennent: The Academy have been frequent collaborators, lenders, and copresenters of our film programs and exhibitions. They are presenters of the Gabriel Figueroa exhibition and also presented Stanley Kubrick. And, of course, the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures is slated to open right next door in 2017 or 2018. How will the presence of the Academy Museum influence your thinking about film at LACMA?

Salvesen: They’re an incredible resource. This interval while they consider the formation of their museum from the ground up—from staffing to exhibition programming to build-out—is a great time for us to be working together, getting to know each other, our collections, approaches, and priorities. We’ll be able to be in sync and complementary when they’re open, and offer an incredible range. There will be nowhere else in the world where a visitor can encounter that in-depth material relating to the industry and its guilds, and the specificity of Hollywood and its influence worldwide over at the Academy; and only steps away come to see exhibitions where in some instances related materials are interpreted differently, where alternative models are presented, where we can show a spectrum in dialogue with each other.

Benson: The overlap is tremendous. There are levels of expertise, issues of preservation, even knowledge of the technical aspects of filmmaking that enrich our understanding of what artists are doing.

Gonzalez: And there’s a tremendous curiosity among filmmakers to go into a different realm. Agnès Varda is a prime example. She spent 40 years of her career mostly making films for a film audience. In the beginning of the 2000s she started to be invited to contemporary art spaces and biennials. She decided that she was going to become an artist at the ripe age of her mid-70s.

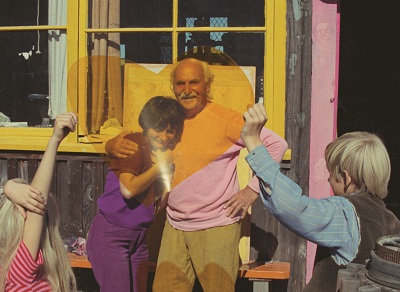

Agnès Varda's film Mur Murs (Mural Murals), 1980, © ciné-tamaris

Agnès Varda's film Mur Murs (Mural Murals), 1980, © ciné-tamaris

Tennent: In partnership with The Film Foundation, LACMA helped to restore four films by Varda, which have screened. Can you say more about the related exhibition, Agnès Varda in Californialand?

Gonzalez: The films that have been restored are four of five films she shot in California. I was wondering, how can we activate this restoration? How could we do something in the galleries? I started thinking about a work I had seen by her in 2007, where she had literally transformed the celluloid remnants of a film that she could no longer send on the road because it was too far deteriorated. She transformed into an artwork—a beach cabana. For her, this was about creating a space for reflection and a space for the memory of this film—which was actually a sour memory because the film was a huge failure commercially! When I asked her if she would do it again here in Los Angeles, she said “Oh, well I did make another huge failure when I came to Los Angeles and tried to break into Hollywood.” She made the film LIONS LOVE ( . . . AND LIES) with the two producers of the musical Hair, and the Warhol superstar Viva. It was the darling of the midnight movie circuit, but for Columbia Pictures that’s not what they were shooting for! So again she has transformed that.

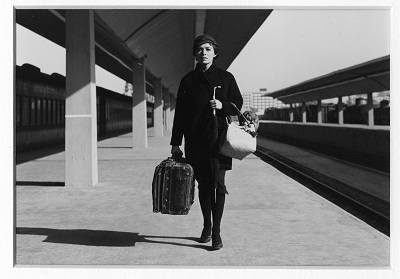

Still from the short film Uncle Yanco, Agnès Varda, 1967, © ciné-tamaris

Still from the short film Uncle Yanco, Agnès Varda, 1967, © ciné-tamaris

Tennent: So Varda has really become a perfect example of how the worlds of art and film are not so distinct.

Gonzalez: She’s always argued that those worlds should be more porous. Artists have always driven this.

Benson: It’s this fluidity that artists have, and Hans Richter is another example—someone who worked completely as an artist at one point in his life, and during the 1930s especially was a professional filmmaker running a film studio.

Tennent: Artists don’t draw the same lines that academia draws.

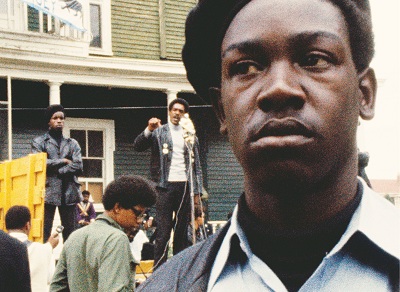

Agnès Varda's short film Black Panthers, 1967, © Agnès Varda

Agnès Varda's short film Black Panthers, 1967, © Agnès Varda

Benson: Especially today, in the most recent generations of artists. Training was often very traditional, even post–World War II. MFA programs were overly specialized, and artists finally decided to ignore that. One day they would make a video, another day they would make a painting, another they would do photography. We really need to benefit from this creativity and what it tells us about the world we live in.

Gonzalez: And our partnership with Film Independent takes that even further. [Film Independent curator] Elvis Mitchell has been a great role model in pushing the agenda for a broader understanding and appreciation of pop culture. Film is just one part of it. There’s also television, YouTube, and all the content developing on the web.

Salvesen: The channels of distribution have been breaking down, and it connects with what we were saying about how things are made; how they are shared and displayed also evolves. This is now a time when a museum can insert itself into those networks and become a significant site for thinking about film.