I’ll admit I have little interest in an exhibit whose focus is based primarily on the gender of the artist. That said, if in some alternate universe (or blogosphere!) I was asked to organize such a show, I’d be glad to be able to share with my audience the depth and breadth of female photographers found in the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection. In See the Light—Photography, Perception, Cognition: The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, the presence of women practitioners is felt throughout the 200-plus works that are featured in the loosely chronological display that covers the invention of photography through to the late 1980s.

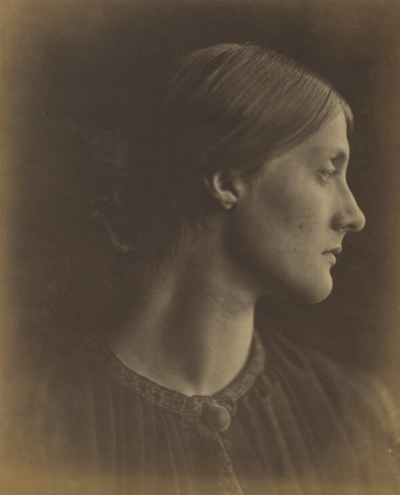

Early adapters abound, such as Julia Margaret Cameron and her eerily contemporary portraits from the late 1800s. There is a presence about the works—I can almost feel the air around her sitters.

Julia Margaret Cameron, Ms. Herbert Duckworth (née Julia Jackson), c. 1867, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation and Carol and Robert Turbin

Julia Margaret Cameron, Ms. Herbert Duckworth (née Julia Jackson), c. 1867, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation and Carol and Robert Turbin

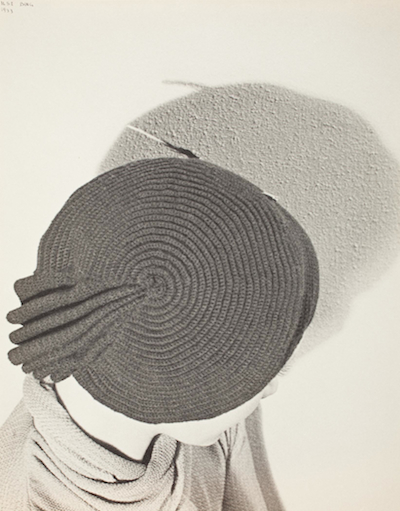

And yes, women captured women in a way that was, by default, different from (if not better than) their male counterparts. Beyond Cameron, my eye finds the 1930s California modernist Ilse Bing and her experimental view from above. The unique perspective, seen in this image below, is the result of a modernist sensibility regarding composition, which is married with a desire to depict a more modern woman.

Ilse Bing, Knitted Round Cap, 1933, printed 1933, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation and Carol and Robert Turbin, © Estate of Ilse Bing

Ilse Bing, Knitted Round Cap, 1933, printed 1933, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation and Carol and Robert Turbin, © Estate of Ilse Bing

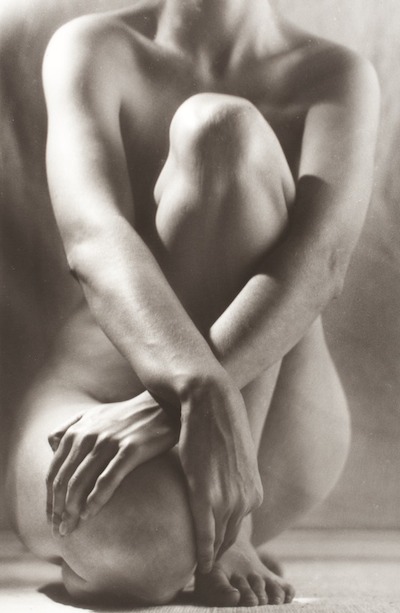

Back to a classic presentation of the female form: the nude. In Ruth Bernhard’s iconic 1960s Classic Torso with Hands (many of you many know her Nude in the Box better), the body serves as a sculptural entity, enabling Bernhard to organize the play of light and shadow. It also shows how shades of gray can create a “landscape” and how the subject's head is truncated in a way that makes this torso sculptural first and sensual second. Though I’m wondering what we would all be thinking if the author was male . . .

Ruth Bernhard, Classic Torso with Hands, 1962, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, Ruth Bernhard Archive, Princeton University Art Museum, © Trustees of Princeton University

Ruth Bernhard, Classic Torso with Hands, 1962, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, Ruth Bernhard Archive, Princeton University Art Museum, © Trustees of Princeton University

The progression of photographic practice as represented by women artists continues within the four “chapters” of See the Light. They are: "Descriptive Naturalism," "Subjective Naturalism," "Experimental Modernism," and "Romantic Modernism." These chapters bracket not only the advances in photography, but the progression of thinking by scholars in the fields of perception, psychology, and neurology. The exhibition traces the idea that all such advances in either the photographic arts or the sciences happened in tandem with these scientific discoveries.

The photographic eye went through modifications as understanding of the mechanics of human optics developed, meaning both the eye as a machine (not unlike the camera), and, later, our grasp of what the brain does with this received imagery.

My favorite chapter, "Experimental Modernism," also has a good proportion of female artists. Intriguingly, Berenice Abbott is one who moves from 1930s work describing a street scape, to the late 1950s, when she crosses over on our "Experimental Modernism" chapter with work done while at MIT creating imagery for use in teaching physics. The presentation elaborates on one career track the ideas in and around visual thinking that are the essence of this exhibit.

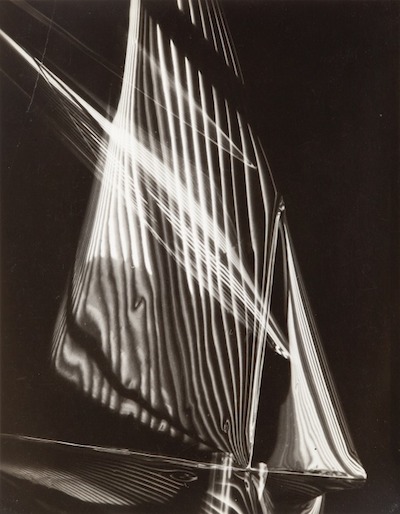

Back to the fun being had in "Experimental Modernism." Even within each imposed division there is still an early, middle, and later period. Follow how the eye/mind works within this trio that runs from 1936 to 1940 to 1947. First, Margaret Bourke-White’s abstracted and monumental view of a dam, next Carlotta Corpron’s equally monumental distorted light (a play on perception), and Ruth Mandel’s newly defined “landscape” of a storefront window (this image asks the viewer to accept interior and exterior on one picture plain, and surface reflections as equal to background shadows).

Carlotta M. Corpron, Fluid Light Design, 1940, printed c. 1940, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © 1983 Amon Carter Museum of American Art

Carlotta M. Corpron, Fluid Light Design, 1940, printed c. 1940, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © 1983 Amon Carter Museum of American Art

Rose Mandel, On Walls and Behind Glass, 1947, printed 1947, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Rose Mandel Archives, all rights reserved

Rose Mandel, On Walls and Behind Glass, 1947, printed 1947, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Rose Mandel Archives, all rights reserved

These next two experimenters are also great examples of early/later imagery: 1950s Germany and 1980s America. We likely wouldn’t posit these two artists—or time periods or the county of production—together, but that’s the wonderfully freeing and, for many, new way of looking at the images that make up the history of photography on display in See the Light.

Ruth Hallensleben, Interior Structure—Factory, 1950s, printed 1950s, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Ruth Hallensleben / Ruhr Museum Photo Archive

Ruth Hallensleben, Interior Structure—Factory, 1950s, printed 1950s, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Ruth Hallensleben / Ruhr Museum Photo Archive

Barbara Kasten, Construct NYC 11, 1984, printed 1984, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Barbara Kasten

Barbara Kasten, Construct NYC 11, 1984, printed 1984, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Barbara Kasten

Picturing these next two women, Mostyn in 1850s and Enos in the 1970s, separated not only by time and their approach to depicting nature, but of course, by the very tools available to enable them to conceive of such imagery. Enos actually went back in time a bit, using a stereoscopic process popular in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Images are viewed in pairs (representing the left and right eye view) through a stereoscopic viewer; optically the brain fills in the overlaps of both images and creates another image, one that appears three dimensional.

Chris Enos, Untitled, 1974, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Chris Enos

Chris Enos, Untitled, 1974, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Chris Enos

Henrietta Augusta Mostyn, Tree and Rock, c. 1850, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

Henrietta Augusta Mostyn, Tree and Rock, c. 1850, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

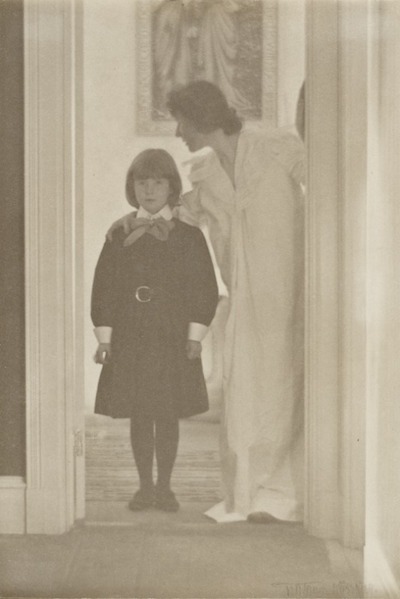

My final walkthrough of See the Light brings me to another juxtaposition with the "Subjective Naturalism" section. Käsebier’s poignant image of mother and child (a family favorite of the Vernons) from 1899. Marjorie Vernon often referred to this image as expressing a sentiment that she and Leonard held dear—the value of family, but also the value of a parent seeming to push a child forward into the world, proclaiming, go forward and create something.

Gertrude Käsebier, Blessed Art Thou among Women, 1899, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation and promised gift of Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

Gertrude Käsebier, Blessed Art Thou among Women, 1899, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation and promised gift of Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin

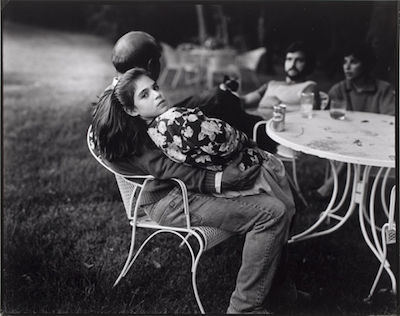

Marjorie was feisty enough to include this contrasting image in their collection: another subjective view on the theme of parent and child by controversial photographer (depending on your perspective) Sally Mann.

Sally Mann, Untitled (Man on Lawn Chair with Girl in His Lap), 1985, printed 1985, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Sally Mann, courtesy Gagosian Gallery

Sally Mann, Untitled (Man on Lawn Chair with Girl in His Lap), 1985, printed 1985, The Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Sally Mann, courtesy Gagosian Gallery

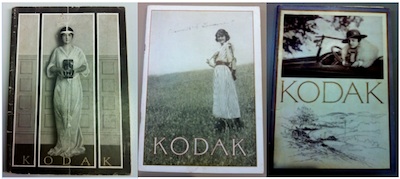

It’s worth noting that the photography industry focused on the female demographic from the very beginning. Even then such early adapters brought the camera into the household and made it increasingly relevant part of everyday life, as well as becoming key practioners. Below is a selection of Kodak instructional manuals that would have been in circulation as early as the late 1880s and early 1900s—note each cover depicting a woman practicing the art of photography.

Kodak pamphlets, courtesy Stephen White, Collection II

Kodak pamphlets, courtesy Stephen White, Collection II

Perhaps when you visit this exhibit you will start to move around the show as I have here—in terms of cognition, subjectivity, and perception, that is, not just the gender of the artist!

Eve Schillo, curatorial assistant, Wallis Annenberg Department of Photography