This is the second of a two-part series focusing on the Vernon Oral History Project. (Read part one here.) Ryan Linkof, Ralph M. Parsons Fellow in the Wallis Annenberg Department of Photography, discusses his experience working on the project.

I came to this project without preexisting personal and professional links to the Vernons, so, for me, this really was a history. It was, from the start, something I could think about in historical terms. This distance afforded me certain advantages, in the sense that I could approach the material objectively, but it also meant that I wasn’t always attuned to some of the personal histories that bound the Vernons to the Los Angeles photo world.

This is where Eve came in. She provided an essential element of personal affinity and connection, and she was able to tease out anecdotes and ask questions about personal details that I wouldn’t have known to ask. As time passed, I have had the distinct pleasure to learn much more about the Vernons and those who knew them. Given this, my objective distance began to wane. It has been a great honor to meet the participants and to get to know the Vernons, if only through their collection. The Vernon Oral History is comprised of a series of overlapping histories. It is, primarily, a history of a collection, but it is also a document of the last quarter of the 20th century in the history of art, arts institutions in Los Angeles, and the global market in art photography. It is, more intimately, a collection of personal histories about two people and those they touched.

Frederick H. Evans, A Sea Of Steps—Wells Cathedral, 1903, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Frederick H. Evans, courtesy Janet B. Stenner

Frederick H. Evans, A Sea Of Steps—Wells Cathedral, 1903, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Frederick H. Evans, courtesy Janet B. Stenner

I initially approached the project as I had been trained to do in graduate school: I viewed it, rather impassively, as set of intellectual problems. I dug into my academic grab bag, used the set of tools I had honed, and made a list of intellectual “deliverables.” The project, I told myself, would illustrate the role of collecting in a variety of crucial aspects of art history: canon formation, the development of art markets, the symbiosis between collectors and museums, the forging of social and artistic networks, the nature of the connoisseurial “eye,” as well as narrating a particular story about the interactions of artists, curators, dealers, and gallerists.

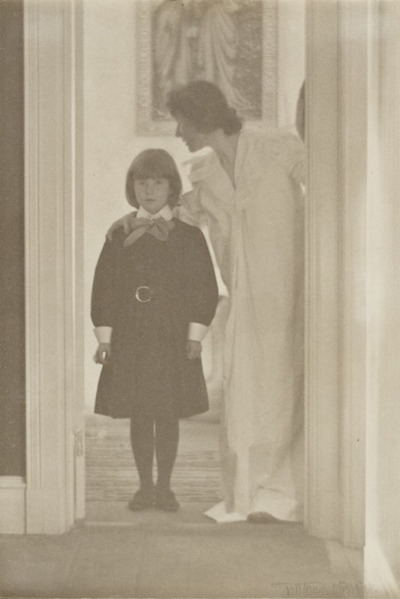

Gertrude Käsebier, Blessed Art Thou among Women, 1899, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Estate of Gertrude Käsebier

Gertrude Käsebier, Blessed Art Thou among Women, 1899, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Estate of Gertrude Käsebier

I quickly learned, however, that the academic’s typical arsenal wasn’t enough for a project such as this. This exploration required a personal dimension in order to tell a complete and satisfactory story. This wasn’t simply a question of art history: it is also a narrative about a family and people’s lives. First and foremost, the Vernon Collection is a family collection—a collection built by a family (in a limited and an expansive sense of that term), as well as a collection built for a family. It reflects an aesthetic interest in interpersonal dynamics and sentimental connections between mothers, fathers, daughters, sons, friends, and acquaintances. It was always intended to be shared between a group of people with similar values and aesthetic interests.

Although this project tells a story about people, it also tells a story about objects: works that emerge in the oral histories as common touchstones. In learning about the growth of the collection, it quickly became clear that particular works held pride of place in the Vernons’ holdings and in their home.

Frederick Evans’s Sea of Steps—mentioned in every oral history that we conducted—was a piece that was close to Leonard’s heart. It was one of the final works he purchased, after much patience. Gertrude Käsebier’s Blessed Art Thou among Women, purchased for Marjorie by her husband, had significant personal value and long held a privileged place in the Vernons’ home. In many ways, the work represents something essential about their collection and the type of photography that lived in their home. In the words of close friends Mike Weaver and Anne Hammond, “Marjorie experienced the work as a human subject that transcends all sectarian beliefs. It embodies the great value Marjorie attached to all tender relations between people, especially between young and old.”

The collection has surprising strengths that express the broad collecting and intellectual interests of the Vernons, as many of the participants of the oral history project noted. For example, the Vernons collected Central and Eastern European modernist photography long before it had significant market value or prominence in major museums. Just when it seemed that we had the Vernons figured out, their collection would tell a different story.

Alma Lavenson, Untitled (Child with Doll), 1932, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Alma Lavenson Archives. All Rights Reserved.

Alma Lavenson, Untitled (Child with Doll), 1932, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon Collection, gift of the Annenberg Foundation, acquired from Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin, © Alma Lavenson Archives. All Rights Reserved.

The oral history provides a very palpable sense of how these artworks were a vital part of the fabric of their daily lives and social events. The collection encouraged people to come together around photography through discussions in their home and regular gallery and studio visits. The Vernons championed the works of some of the artists whose studios they frequented, such as Robbert Flick and Anthony Hernandez, long before they became fixtures in museum collections. During our many interviews, we uncovered remarkable revelations about the Vernons’ personal relationships to artists. Perhaps the most compelling story involved the artist Alma Lavenson, who was revealed to have had a fascinating biographical link to Marjorie. I will coyly refrain from divulging the details in this article, but the story will appear in full when the oral history is completed, after which it will be publicly accessible on lacma.org. What I will say, however, is that this personal story underscored the fact that oral history is essential in incorporating this collection into LACMA’s photography department. The works of art might speak for themselves, but the oral history provides a nuanced perspective about what this collection was and the intimate relationships embedded in the practice of collecting.

Ryan Linkof, Ralph M. Parsons Fellow, Wallis Annenberg Department of Photography