It is perhaps in bad form to pick favorites in any exhibition. Like children, we sometimes tell ourselves, each work is special and unique in its own way. That said, I seem not to be able to help myself when it comes to the current show Under the Mexican Sky: Gabriel Figueroa—Art and Film, which I had the great pleasure to work on with LACMA curators Britt Salvesen and Rita Gonzalez and the energetic team from Fundación Televisa, led by curator Alfonso Morales. Among the 330-plus works in the show—all rich and gorgeous in their own right, to be sure—are four large color prints for which I have developed quite a fondness. Tucked in the southwest corner of the Art of the Americas Building, the enlarged film stills shot by photographer Ángel Corona Villa depict scenes from El amor tiene cara de mujer (Love Has a Woman’s Face), a film Figueroa made with director Tito Davison in 1973.

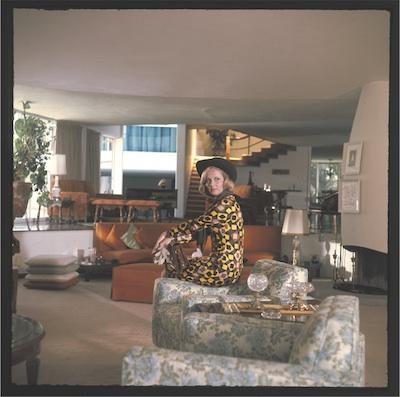

Ángel Corona Villa, still from El amor tiene cara de mujer, directed by Tito Davidson (1973), film version of the televnovela, 1973, printed 2007, © Televisa Foundation

Ángel Corona Villa, still from El amor tiene cara de mujer, directed by Tito Davidson (1973), film version of the televnovela, 1973, printed 2007, © Televisa Foundation

In part, my attraction to these objects is animated by a sort of perverse contrarianism. Made in the throes of the post–Golden Age period of Mexican cinema, which saw the waning of much of the creative energy that catapulted Mexican film to global attention in the 1940s, the work represents a divergence from the type of film most commonly associated with Figueroa’s oeuvre. While he was known for his epic black-and-white tableaux, sweeping landscapes, and narratives with heavily didactic political themes, El amor tiene cara de mujer looks markedly different from the stills and projections that precede it. This is why they stand out so starkly on the wall, and, I’m certain, part of the reason why I find them such intriguing images. The film expressed a bright, candy-colored sensibility that was a clear departure from his earlier cinematographic style.

Gabriel Figueroa, film still from Enemigos, directed by Chano Urueta, 1933, © Gabriel Figueroa Flores Archive

Gabriel Figueroa, film still from Enemigos, directed by Chano Urueta, 1933, © Gabriel Figueroa Flores Archive

The film’s subject matter was also quite a departure for Figueroa. Adapted from an Argentinean telenovela that had made a splash in Mexico in 1971, the film was a female-centered melodrama seemingly detached from the politicized iconography that had been such an essential part of Figueroa’s early career, and which he had developed in dialogue with the masters of Mexican muralism, such as Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco.

Ángel Corona Villa, still from El amor tiene cara de mujer, directed by Tito Davidson (1973), film version of the televnovela, 1973, printed 2007, © Televisa Foundation

Ángel Corona Villa, still from El amor tiene cara de mujer, directed by Tito Davidson (1973), film version of the televnovela, 1973, printed 2007, © Televisa Foundation

Depicting a series of scenes in an upscale Mexico City boutique, the four stills are a tour-de-force portrait of the garish women’s fashions and demonstrative interior décor of the 1970s Mexican elite (or at least their telenovela surrogates). Say what you will about the outrageousness of the characters’ choice in clothes and furnishings—there is something truly visually seductive about the bravado of those gold and black patterns, the height and solidity of those coiffures, and the sheer abundance of the candles shoved into that golden candelabra. I challenge you not to find at least some joy in looking at these images.

Ángel Corona Villa, still from El amor tiene cara de mujer, directed by Tito Davidson (1973), film version of the televnovela, 1973, printed 2007, © Televisa Foundation

Ángel Corona Villa, still from El amor tiene cara de mujer, directed by Tito Davidson (1973), film version of the televnovela, 1973, printed 2007, © Televisa Foundation

These film stills also got me thinking about the place of the telenovela—and the soap opera more broadly—in the history of art and contemporary museum display. While there are marked differences between the Latin American telenovela and the American soap opera—for one, American soaps can last for decades, while the telenovela has a defined number of seasons—parallels between the two forms undoubtedly exist. Curiously, it seems that contemporary art and “the soaps” have more overlap that one might think.

My mind immediately wandered to the soap opera “performance art” of James Franco, who created the role of Robert James “Franco” Frank, a multimedia artist and, ahem, serial killer, for the American soap opera General Hospital in 2009 (appearing intermittently on the program through 2012). Coincidentally, Franco admitted that his interest in this character emerged after the performance artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña, an artist whose work is featured in the Figueroa exhibition, paid a visit to his class at CalArts. Franco brought his character into the “real” art world in June 2010 with the event “Soap at MOCA: James Franco on General Hospital,” which saw the fictional Franco character displaying his art at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Included in the project was a performance by artist Kalup Linzy, dressed in demonstrative drag with a cartoonish flowing wig and a sequined dress that, come to think of it, might have fit in quite well in El amor tiene cara de mujer.

This collapsing of fantasy and reality, the masquerade of the soap opera and the spectacle of contemporary art, was intended to raise questions about legitimacy and artistic taste that have a long history in performance art. By placing the soap opera within the context of the art museum, Franco was asking how the art museum confers value by its very existence—does something become art simply because it is placed in a museum? What is essentially a very basic (and by no means new) question reverberates quite broadly, and spurs me to ask: have we elevated El amor tiene cara de mujer to the lofty heights of “art,” by including it in an exhibition in a world-renowned museum?

Of course, Franco is not alone in creating a dialogue between the soap opera (and the telenovela) and the art museum. Andy Warhol’s 16mm film Soap Opera (1964), perhaps most notably, predated Franco’s performance by nearly half a century. There is also an established tradition of using the telenovela—a prominent part of many Latin American cultures, and often a major cultural export—within Mexican art and photography. The photographer Antonio Caballero created fascinating narrative studies produced for the still-photography serialized fotonovelas in the 1960s and 1970s, which are intriguing objects in their own right. His images, as was typical of the genre, produced a melodramatic iconography that mirrored what was being broadcast on telenovelas. More recently, artist Yvonne Venegas was asked by Mauricio Maillé, director of the Visual Arts Department at Televisa—who was an important participant in the Figueroa exhibition—to photograph the final season of the Mexican telenovela Rebelde. The resulting series and book project offers an intriguing look into the cult of telenovela stars, as well as the enduring visual language of the form, which evidently has held on to the vivid colorful palette captured by Figueroa four decades ago.

Ángel Corona Villa, still from El amor tiene cara de mujer, directed by Tito Davidson (1973), film version of the televnovela, 1973, printed 2007, © Televisa Foundation

Ángel Corona Villa, still from El amor tiene cara de mujer, directed by Tito Davidson (1973), film version of the televnovela, 1973, printed 2007, © Televisa Foundation

I suppose what I find so intriguing about these four film stills, when forced to account for my interest in them, is that they represent a conflict between competing ideas of taste and aesthetic worth. Often considered to represent the lowest point in Figueroa’s creative career, and the product of an entertainment form that is, more often than not, excluded from the refined atmosphere of the art museum, they seem oddly out of place, as if they don’t belong. In this way, the images are a prompt, asking the viewer what it is that they expect to see in an art museum. They also make us think about the creative and professional choices made by artists and filmmakers that do not fit the neat categories we create for them. Certainly not his best work, El amor tiene cara de mujer is nonetheless part of an interesting episode in Figueroa’s career. And to paraphrase a cheap tagline for a telenovela, this is an episode that is simply too good to miss.

Ryan Linkof, Ralph M. Parsons Fellow, Wallis Annenberg Department of Photography