Is it possible that an African American can view the exhibition Shaping Power: Luba Masterworks from the Royal Museum for Central Africa without a tinge of discord and disconnect; or are we to be washed over, teary eyed, and spellbound in awe of this immense beauty that is before us? Here we must travel through time to a dark period as Africans who are not pure bloods. One must peer at a world or cosmos whose complexity was assured and complete. Luba Masterworks stands in a parallel universe, with its profound sacred objects, beatific scars, and intimate rituals of glorification. Simultaneously, we’re wretched back to another darker world of bondage, an adopted god and the abstract scarification of the whip. Mary Nooter Roberts and Allen F. Roberts write in their book Luba (Visions of Africa) that “the Luba Kingdoms never constituted an ‘empire’ . . . , even the main Luba Kingdom was first and foremost a construction of the mind.” I found the intellectual weight of this notion that Luba’s political strength comes from spiritual power and the beauty of their arts was in profound accordance to all great civilizations.

Caryatid stool, Africa (Democratic Republic of the Congo, Luba Peoples), The Royal Museum for Central Africa, collection RMCA Tervuren, photo R. Asselberghs, RMCA Tervuren ©

Caryatid stool, Africa (Democratic Republic of the Congo, Luba Peoples), The Royal Museum for Central Africa, collection RMCA Tervuren, photo R. Asselberghs, RMCA Tervuren ©

Upon entering the African gallery, one is confronted with a hall of a kingdom that is past and yet is present. A wooden female figure, a quite small caryatid stool, kneels before you. She is kitenta, a spirit capital. Holding up a thick disk, her eyes are cast down. A choker of giant blue beads adorn her neck and small white beads circle her waist—she is poised. Her extended navel is surrounded by precise, patterned scars that texture the nut-brown wood, which darken toward its edges as she kneels on an equally thick disk. The Mulopwe (the king) is dead. One is in the presence of “a lieu de memoire,” where his spirit resides. This was the king’s throne as is the other, larger stool in the exhibition. Female power is at the very heart of Luba royal arts, for kings were represented by women “who surround, uphold, and empower them.” Enshrined in a complex ritual, women were endowed with conferring and giving life. “The foundation of kingship is the women.”

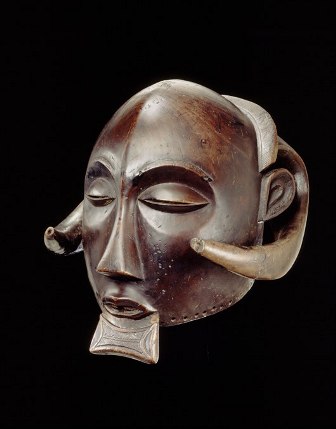

Male Mask, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Luba Peoples, 19th Century, Wood (Schinziophyton rautaneii), Royal Museum for Central Africa, RG 23470 (collected by O. Michaux in 1896), Photo R. Asselberghs, RMCA Tervuren ©

Male Mask, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Luba Peoples, 19th Century, Wood (Schinziophyton rautaneii), Royal Museum for Central Africa, RG 23470 (collected by O. Michaux in 1896), Photo R. Asselberghs, RMCA Tervuren ©

At the center of the gallery, as out of the marshland of Lualaba River as it were, a buffalo man, the Mbidi Kiluwe, the hero, stares out of a powerful dark buffalo-horned mask as if at the center of gravity. It was remarked that his skin is “black like the night.” He is a masterful hunter and blacksmith, the one that made the Luba Epic—the oral narrative—possible. He imparted knowledge, stimulated memory, and harnessed the spiritual world. He is the touchstone of the Balopwe and the secret association called Mbudye, in which all-esoteric wisdom, customs, and complex rituals are transformed and transferred. The gallery holds these instruments of the intermediaries between the world of mankind and world of the spiritual ancestors.

Bowl-Bearing Figure, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Luba-Henba Peoples, 19th Century, Wood (Ricinodendron rautanenii), Royal Museum for Central Africa, RG 14358 (Collected between 1981 and 1912, gift of A.H. Bure), Photo R. Asselberghs, RMCA Tervuren ©

Bowl-Bearing Figure, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Luba-Henba Peoples, 19th Century, Wood (Ricinodendron rautanenii), Royal Museum for Central Africa, RG 14358 (Collected between 1981 and 1912, gift of A.H. Bure), Photo R. Asselberghs, RMCA Tervuren ©

I came upon the Bowl Figure that holds chalk (mpemba), the sacred white substance of enlightenment. I thought about how deeply personal each adornment embodied a sacred expression, spells of grave enchantment. In this world, the Mbudye members and ruler would drink palm wine and other secretive potions from the ceremonial Kiteya bowls and cups, smoke from the pipe, whose figure’s genitals impart complex social and ancestral relationships that foster personal transformation. Earth spirits in the form of lizards would be carved into lids of bowls. Antelope horns, smoke stained, packed with medicinal substance for these spirit figures, the Bilumbu, had transcendent power of locomotion, not only seeing into the beyond, but may have traveled to the beyond. There were royal spears, staffs of office and ceremonial axes, which provide metaphors for “breaking a path.” How needful! Africa—a beckoning world—the “Heart of Darkness,” as Joseph Conrad’s ponderous narrative of barbarians in contrast to “civilized society,” dense in the myth of the “savages,” the “other,” as it is suggested. Marcus Garvey offered a dreamland of return, a land of sad, exotic contradiction, where innocence died. Mary Roberts’s scholarship gives us a complex Luba society of profound depth, and yet it, too, would be a counter narrative to another world tragically simpler, a cosmic failure—ours was where the shame of skin and chained servitude and the endless nightmare of its terror, cruelty, and violence was itself a continent within a continent, creating its own bleak weather, day in and day out, year after endless year, unrelenting, in deep time, hollowed out until memory knew no other. I am amazed by the sophistication of the Luba people: the intricacy, the subtlety, and the sheer fundamental naturalism interwoven with spirituality that is based in the earth, and honors the corporeal, mystic mystery of the life force. Ironically, by a cruel dent in history, we, as a people attenuated, became the modern embodiment of the existential man who was denied his history. When I was a boy, we were Negros. Maybe the constant adjusting of the name we were to go by; Negro, colored, blacks, and now, African American, distilled its own formal, paradoxical, elusive identity. As if we were a species of an indeterminate form, aliens from an alternate universe. And one must invent the self through the eyes of the chains that bind us. So I come to this Luba cosmos as an explorer, not as progeny. Only our DNA knows the truth. What were left unmoored were the voices, unencumbered energy in our hips and bodies, the acrobatic motion of a million rituals still in tune, in rhythm, still dancing in the blood of time. In the new world, there would be no hero, no Mbidi Kiluwe. The mother would be taken from you. No secret association, no Mbudye, no Bilumbu diviner that slips through shadows, no radiant Mboko reading the will of the spirits, no healing and no problem solving, no intermediaries to the darkness they confronted, only the precarious, invented world would be theirs. For the most precious of all Luba artifacts is the memory board, the Lukasas, here the universe of time and place could be read, could be seen through the constellations of beads, shells and bits of metal offering a mnemonic code, geometric patterns of deeply esoteric meanings. But there would be no “men of memory”—thus we are the people of dreams. The sheer beauty of the Luba culture was on, some level, beyond imagination, idealization, or at least I was unprepared for its depth—the elegant coiffure, the scars, the animals, and the abstraction that wasn’t an abstraction but a symbol of meaning, the distinctness, a sign of a deeper realization. It was the infinite sky on the other side of the world. Hylan Booker