Popular interest in all things Korean has been growing in the United States. Samsung and Hyundai are now familiar household names, South Korea’s rapid economic expansion continues to defy most predictions, and recent reports on the health benefits of Korean food and the overseas popularity of Korean films, soap operas, and K-pop have captured the attention of many, especially those of us living in Los Angeles. But even ardent Korea-philes may be surprised to learn that many of the social customs, beliefs, and traditions still prominent in Korea today can be traced back to the Joseon dynasty.

The exhibition Treasures from Korea: Arts and Culture of Joseon Dynasty, 1392–1910, which just opened at LACMA on June 29, brings to Los Angeles the art and culture of this last dynasty of Korea. Most of the nearly 150 works in the exhibition, among them national treasures that have never been shown in the U.S., have been generously loaned by the National Museum of Korea as well as other museums and private collections in Korea. This exhibit, which is traveling between the Philadelphia Museum of Art, LACMA, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, is part of an important cultural exchange between South Korea and the United States. In 2013, these three museums, along with the Terra Foundation for American Art, sent to Korea the first-ever survey of American art in the exhibition Art across America, which was on view at the National Museum of Korea in Seoul from February 4 through May 19, 2013, after which it traveled to the Daejeon Museum of Art (June 17–September 1, 2013).

Marked by a grand sense of pageantry, a strong sense of morality, and an unwavering reverence for nature—all characteristic of the Joseon dynasty—this exhibition is the first major presentation of traditional Korean art at LACMA. Treasures from Korea is also the third part of a larger effort to share traditional Korean art with the American audience. The two earlier installments, which featured works from the earlier dynasties of Silla (A.D. 57–668) and Goryeo (A.D. 918–1392), were presented at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, in 2013 and 2003, respectively.

Divided into five themes, Treasures from Korea captures the story of the life of an epic dynasty—its embrace of neo-Confucianism in the belief that the philosophy would sustain the country, how tastes emerged as the upper class developed new ceremonies and events (which then influenced the rest of society), how earlier historic Korean traditions were practiced in the private sphere, and how all these customs and assumptions were tested and reshaped by the pressures of modernization and the infiltration of the West.

The King and His Court

Korea’s Joseon dynasty spanned more than 500 years, overlapping with China’s Ming and Qing dynasties and Japan’s Muromachi, Momoyama, Edo, and Meiji periods. The dynastic founder, Yi Songgye, established Korea’s first secular state based on the principles of neo-Confucianism in a decisive move away from centuries of policies centered on Buddhism. In this revolutionary shift, the long-revered Korean traditions of shamanism (the indigenous religion of Korea), Buddhism, and Daoism, which together had sought to bring& understanding to the rules of nature and the cosmos, became absorbed and integrated into a larger order based on China’s Confucianism, a philosophy of attaining social harmony. Altered to suit Korea’s political needs, this version of Confucianism was known as neo-Confucianism.

This was both a radical and conscious shift espoused by the government to start the dynasty anew. (The name Joseon translates to “fresh dawn.”) Although Korea had historically regarded itself as a sovereign state of China, the implementation of neo-Confucian policies was an important step for Korea in its effort to become an independent country with a healthy respect for China. With the fall of the Chinese Ming dynasty to the Manchus in 1644, Koreans regarded themselves as representatives of the last bastion of Confucianism.

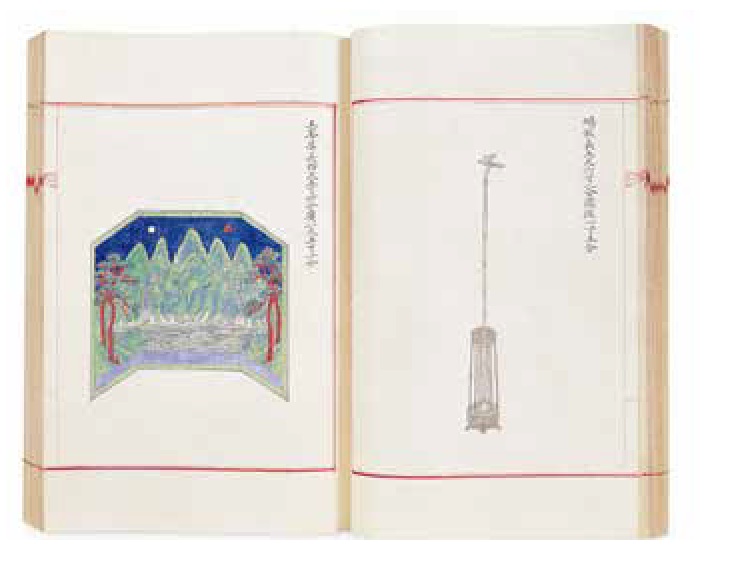

It was of quintessential importance for the newly founded dynasty, with its unfamiliar secular state policies and recently established kingship, to assert its legitimacy. Rituals played a critical role in bringing about a culture of pomp and pageantry thought to ensure continued dynastic prosperity. All festivities demanded a particular presentation and were massive affairs with countless artisans, laborers, and officials engaged in the production of these rituals of the court. The first section of the exhibition, titled “The King and His Court,” showcases the celebration and documentation of important rites of passage for the royal lineage. It illustrates how the birth of a royal was celebrated with large-scale folding screens and placenta jars, how the honoring of new regal progeny included the giving of official titles of rank, and how the welcoming of foreign envoys, royal weddings, and funerals involved colorful, vibrant folding screens and tranquil ceramics. This theme exhibits the regalia and aesthetic tastes of the court, as well as the public life and customs regarded as most important in the life of the king.

Joseon Society

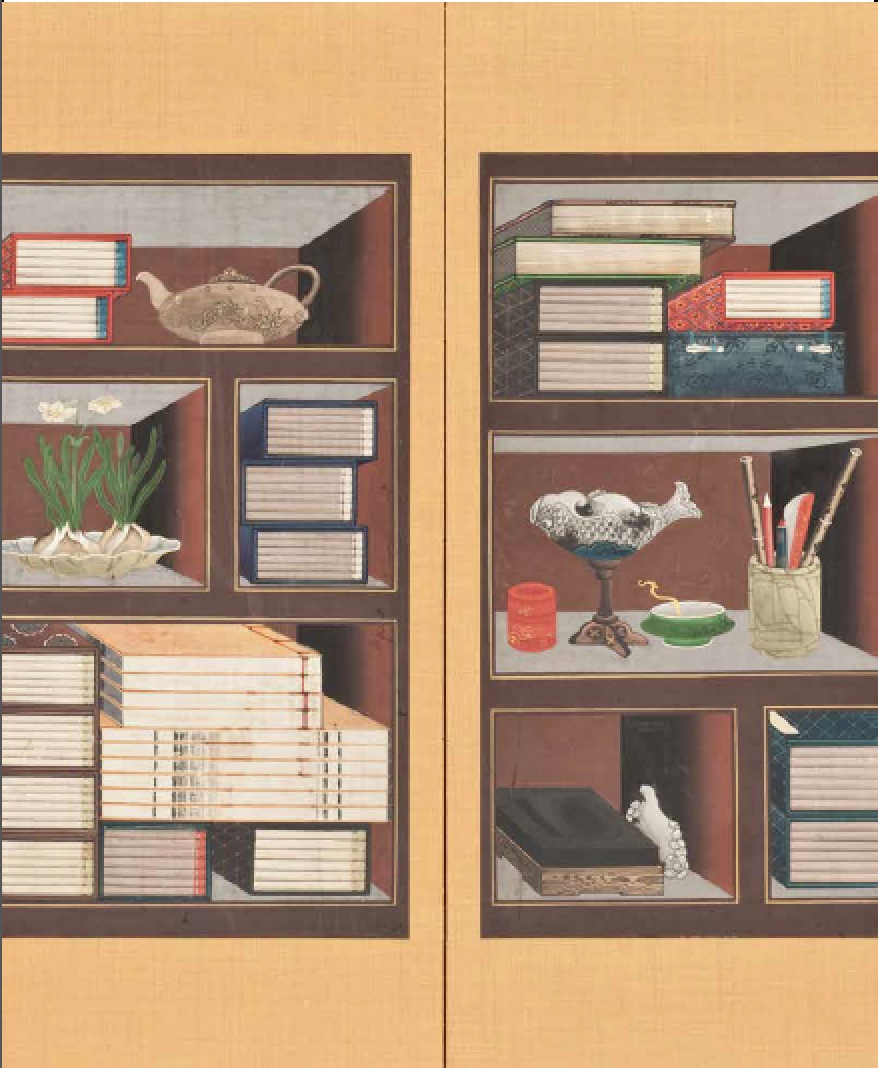

The second theme, “Joseon Society,” explores how the royal aesthetic and adherence to neo-Confucian principles manifested itself in the Joseon upper class and trickled down to the rest of Joseon society. The underlying moral and social culture of the court deeply affected the rest of society. While the majority of the different classes of society were based on heredity, officials of the court secured their positions through government examinations that were based on Confucian teachings. With this, the culture of the scholar-official, or literati, was born. What began as a way to gain a court position evolved into a culture that held scholarship in the highest regard.

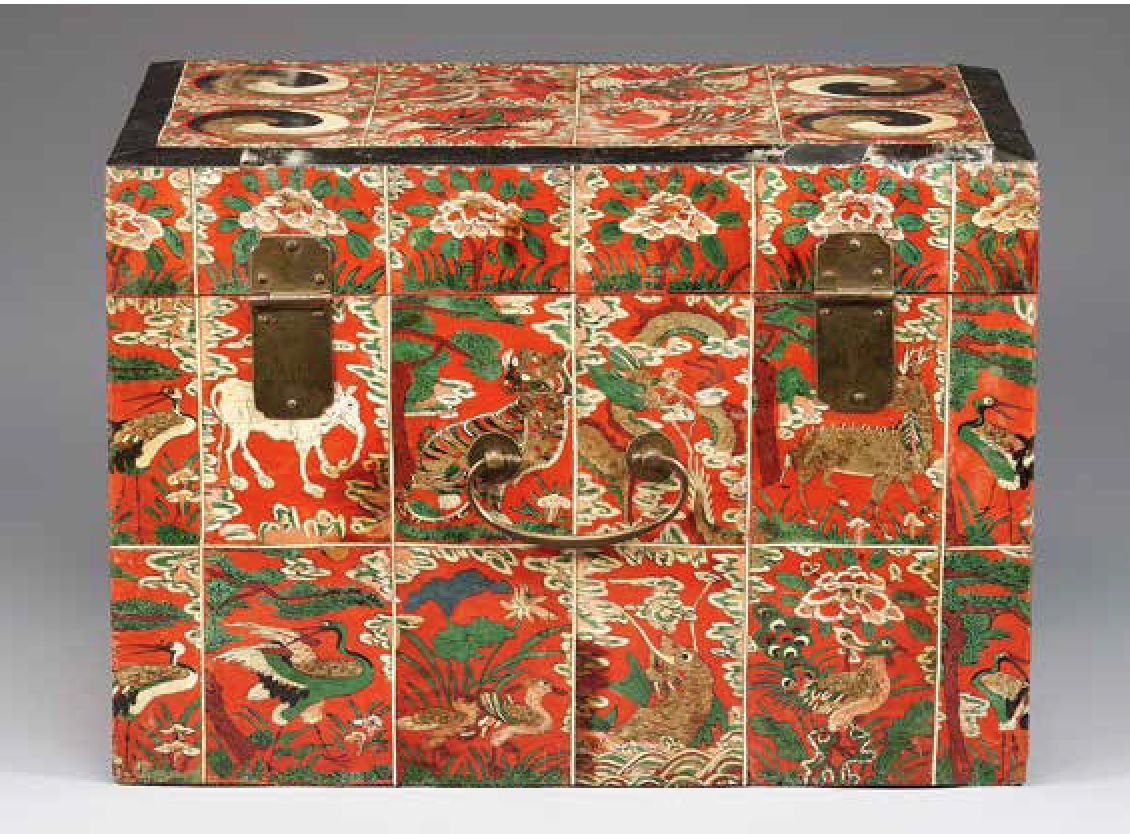

A consequence of this was the widening distinction between men and women. Women did not have a place in politics or the outside world and were relegated to overseeing the house with the primary obligation of producing sons. We see the difference in their roles manifested in the style of furniture, clothing, and choice of objects used by the male scholar-official as compared to the interests and decorative aesthetics of the female in the Joseon household. Symbols of nature, longevity, and good fortune visually populated the arts as ways to convey, acknowledge, and affirm an understanding of the shared importance of these beliefs.

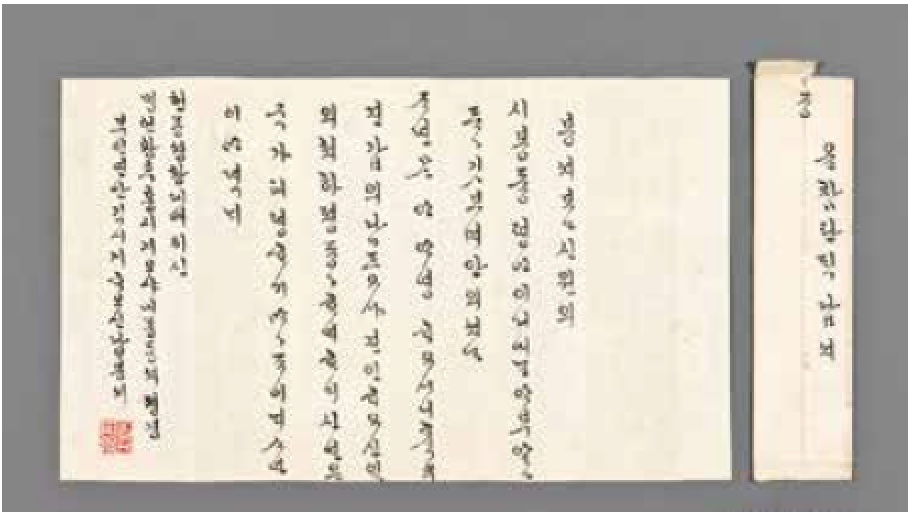

In further efforts to promote Confucian studies, a native script known as Hangeul was developed in 1446. It allowed Chinese classics to be translated, but the new invention had a more far-reaching impact by allowing all members of society, including those who were not educated in classical Chinese, to read and write. It immediately generated a new, popular activity of writing personal letters.

Ancestral Rituals and Confucian Values

The Confucian concept of filial piety made it a moral duty to pay respect to one’s ancestors and, by correlation, to one’s king, making the practice of ancestral rituals an even more pronounced part of Joseon life than it had been in previous times. Korean shaman priests and the Buddhist clergy for centuries practiced respect for, and dedication to, one’s ancestors. Re-envisioned in a new ritualized form, the ceremonies honoring the dead held at the Joseon royal court were believed to control the fate of the country; they were directly linked to proving and protecting the king’s legitimacy and authority. The social obligations expected of every court official quickly relegated these practices to the home, where the precise conduct of the ceremony and the quality of ritual wares used became equated with devotion and respect for one’s ancestors. The exhibition’s third theme takes us into this private realm of ancestor worship.

Continuity and Change in Joseon Buddhism

With Confucian state rites replacing Buddhist ones, Buddhism, which had been the moral and religious stronghold for previous Korean dynasties, was relegated to an even deeper private sphere of individual worship among members of the royal court and society when it came to matters of life and death. Paintings and devotional objects were commissioned to support prayer requests for a long and healthy life and wishes for a successful rebirth in the afterlife. But with the obligation to produce a son, women of both the Joseon court and society became the staunchest supporters. In these requests, all earlier Korean traditions were called upon, and Daoist and folk deities were jointly worshipped in the name of Buddhism.

Joseon in Modern Times

Despite a number of major attacks from China and Japan over the years, the dynasty survived centuries of relative political stability. But with the tide of Western influence, all aspects of the Joseon dynasty were brought into question and in many ways were interrupted. Although foreign influences had made their way indirectly to Korea by means of diplomatic missions to China, by and large the Joseon dynasty protected itself with a foreign policy of isolation. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, Korea was forced to open its ports to trade, a decision that prompted a range of responses from those who staunchly believed that Korea’s identity and independence lay in the strict continuation of neo-Confucian ideals to those who, with the changing atmosphere in the world beyond, believed that the future lay with joining the rest of the world. It’s evident that the introduction of electricity and photography and—in an effort to modernize—the declaration of the Korean empire in 1897 brought stylistic changes in art and uniforms as well as royal household items and books in English. From the pomp and pageantry of the king and his court to their influence on the rest of Joseon society, and from expressions of private individuals to their practice of ancestor worship and Buddhism, the seeming end of a dynasty turned out to be a coming of age as the country began to emerge into the modern period.

It is so often the case: politics affects art. The state policy introduced by early Joseon officials resulted in new artistic production that accommodated the needs of the new dynasty. Largely made by unknown craftspersons and court artists, the art of this period embodied a philosophy and social order that resulted in the longest-running Confucian dynasty in history. And that is a remarkable achievement worth seeing.

A version of this article originally appeared in the summer 2014 (volume 8, issue 3) of LACMA’s Insider.