Unframed is taking a look behind the scenes to profile the creative, dedicated people who make LACMA special. We sat down with archivist Jessica Gambling to talk about her path to becoming a museum archivist, how she decides what to keep, and little-known facts about LACMA.

Tell us what you do at LACMA.

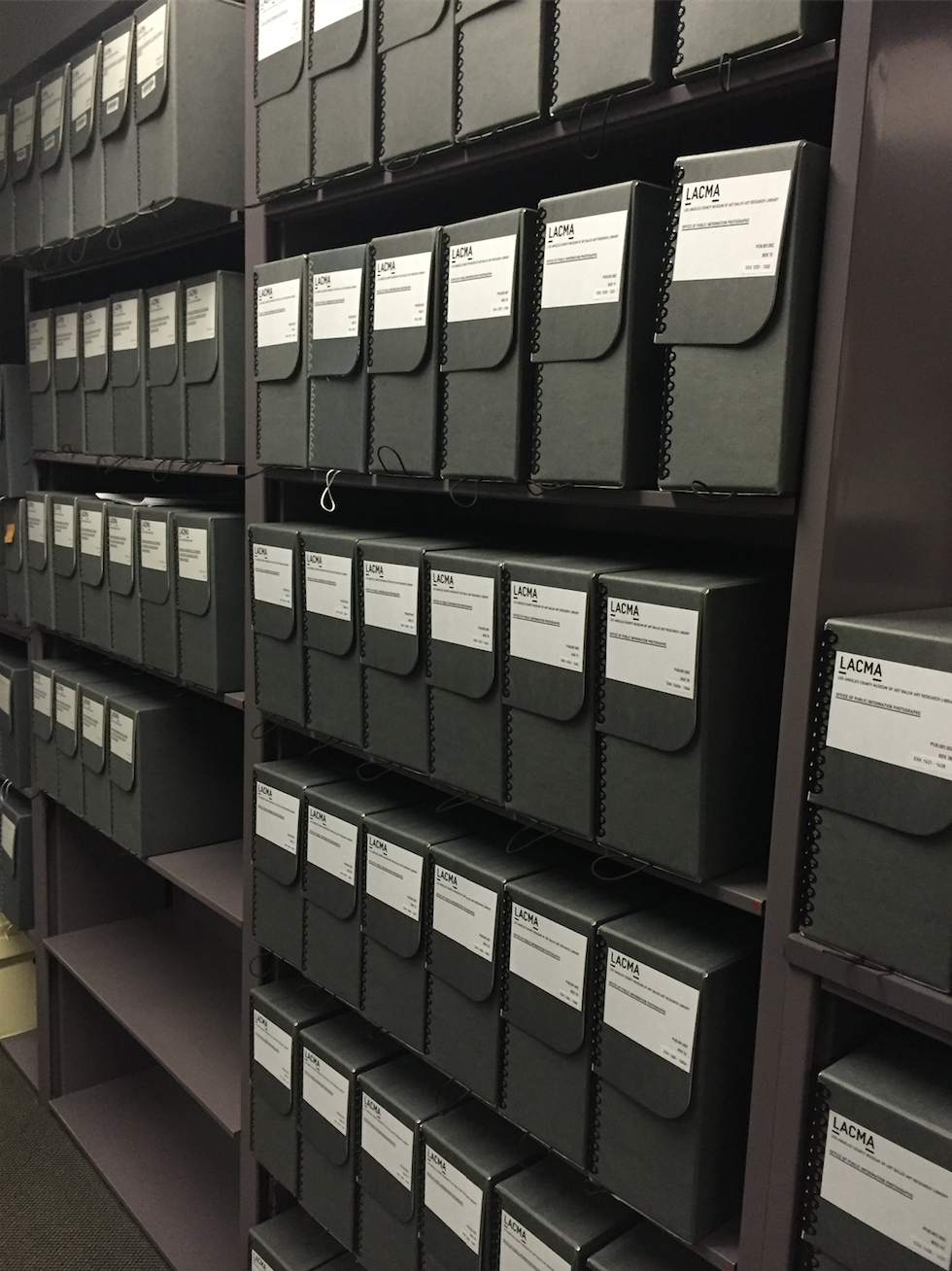

I’m the institutional archivist. I take care of the historical records of LACMA—records that were created in the day-to-day business of the museum, including exhibitions, educational programs, and building the art collections, so that researchers can one day use them to learn about our art collection, its history, and the history of the museum. I’m an archivist specifically for LACMA, as opposed to, say, a manuscript curator, who would acquire records and archives from outside of the institution.

How do you decide what to save for our archives?

Examples of things we keep forever are exhibition records, records about the art collections, things having to do with educational programming, art activities, and film screenings. Things that we wouldn’t keep forever might be financial or HR records. People do their best to weed things out of the records before I process them—private things, duplicates, things that don’t belong. Then I’ll go through them again to see if any additional things should be discarded.

Are these digital files, paper files, or both?

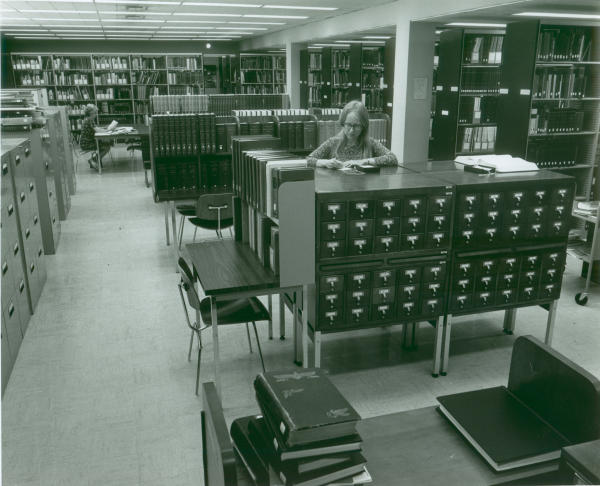

The records that can be processed are the oldest ones, and they’re all paper. If they’re disorganized, I might fix them up a bit. Then I create finding aids, which are documents that describe groups of records as a whole. Those go online, so people from outside and inside the museum can search for them and get in touch with us to come and use them.

Do you digitize the paper items?

We’ll probably digitize some things eventually, but that doesn’t happen on the front end. A digital file has to be tended over the years. Paper will last at least 500 years, maybe longer—there are papyri that are thousands of years old. But a digital file could degrade over the course of just a couple of years. Or the software that’s used to read it might not work anymore, or the necessary equipment isn’t available—it could be on a disk, and you might not have the drive. If we were to digitize something, it would be for access rather than preservation.

How do people make use of the archives?

Somebody’s here right now researching the Black Arts Council that was active at LACMA [from 1968 to 1974].

And sometimes our curators use the archive to research. If they’re planning an exhibition with pieces that might have been shown before, they’ll go to the archives to see what we did last time. Sometimes materials from the archives will actually be in the exhibition: The Presence of the Past: Peter Zumthor Reconsiders LACMA, (June–September 2013), for example, included a lot about Hancock Park, the Tar Pits, the history of LACMA, the architecture of the current buildings. There had always been talk that Mies van der Rohe was originally supposed to build the museum, but we weren’t sure where the proof was. Then, in the archives, we found the actual board minutes, where they’re discussing different architects, and Mies van der Rohe is mentioned. There’s a letter that the board wrote to [trustee] Howard Ahmanson saying, we’ll defer to you, so you can see how the ultimate decision to select the architecture firm of William Pereira and Associates came about. That letter was on display in a case in that exhibition along with architecture models related to LACMA, which are also under my collections.

What was your path to becoming an archivist and working at LACMA?

I was a history major in college, and we had a senior year project that required us to consult primary sources. I did my research at the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library in West Adams. It’s this really neat library and it was such a pleasant experience to go there. I was reading rare books, 17th-century pamphlets on a witchcraft trial, and I loved the space and the process.

I didn’t go to graduate school right away. But eventually, I thought it would be a good idea to go into something where you always have a sense of mission, where you’re doing something good for the world, for society. I was still interested in library research, and I decided to go to library school. While I was there, I worked at the Huntington Library for two years, and got hired as a full-time archivist on another project.

Meanwhile, in about 2007, LACMA applied for a grant to establish its archives. After the first archivist on the project moved on in 2010, I applied for the position. After the grant period ended, LACMA decided to make the archivist position permanent, and I was able to stay on.

What do you enjoy most about being an archivist?

There’s such a variety of things that you get to do. In my first four years as an archivist [before coming to LACMA], I worked in photography collections, including one that involved early-20th-century Southern California history, a mid-century architectural and landscape photographer, the estate of an art photographer, and at the Los Angeles Public Library on aerial photographs from the ‘50s and ‘60s. As an archivist, it’s always best to stay flexible, open-minded, and interested in a lot of things.

Every project is like a master class. And while having subject expertise is helpful as an archivist, there are principles and things you learn in graduate school that help you make good decisions for your archives regardless of whether you know the subject matter.

Tell us about your creative outlet.

I was a singer in college, and I’ve started taking voice lessons again.

What kinds of things do you like to sing?

Italian songs, Italian art songs, opera, classical voice. I do it because I enjoy it and to see if I can do it. Professional opera singers are like athletes. My voice teacher is in the L.A. Master Chorale, and the things they can do are just crazy. And to think, it’s just their body doing that!

What’s one of your favorite past exhibitions at LACMA?

There are so many good ones. I loved California Design. I was really familiar with a lot of the stuff in the show, and then to go and see it installed, and see the objects—that was really fun. It was bright and cheery, and it was really enjoyable to be in there.

My other favorites are From the Archives: Art and Technology at LACMA [2015] and Various Small Fires [2016], which was also an archival show. I think [Various Small Fires] may actually be my all-time favorite, but I’m biased, because it’s basically all about archives and memory.

Tell us something about LACMA that not many people know.

LACMA was the setting of a scene in The Player, with Tim Robbins, and they just came out with the Criterion Collection DVD. For the special features, the Criterion Collection came here and looked at footage that our AV department at the time made during the shoot. They were able to include this adorable 15-minute film about Robert Altman coming to LACMA and shooting a few scenes here over the course of a day or two. It’s a little bit like an in-house VHS tape, very charming and from the early ’90s. It’s professionally made and well done, but it’s also obvious that it was made by LACMA for fun, just to share with staff and Board members.

The library and archives are open to the public by appointment.