They’re always here in the museum—peering at a painting’s surface, walking around the base of a pedestal, scanning a gallery to assess its spread of objects. Artists. For LACMA’s Artists on Art online video series, we reached out to our most devoted fanbase, and deepest resource, to ask them to speak on objects from our permanent collection. A stellar assortment took us up, including, to start with: John Baldessari, Judy Fiskin, Thomas Houseago, Tom Knechtel, Catherine Opie, Alison Saar, Betye Saar, Jacob Samuel, James Welling, and Mario Ybarra, Jr. The videos offer a captivating assortment of ideas on art. What is it, where does it come from, why spend time with it? What does it tell us? Why make it?

I assisted Carol Eliel, curator in the Modern Art department, in organizing the series. We approached each artist with a simple proposition: Come to LACMA to visit with and record some thoughts on a work (or works) of your choice from our permanent collection. And come they did, mostly in blue jeans—no stylists required—to be recorded by Agnes Stauber, multimedia producer at LACMA, in spaces across the museum campus. Looking at a selection of prints by Albrecht Dürer, Jacob Samuel declared his indebtedness to the centuries of historical precedent available to him at the museum: “When a person gets serious about art and being an artist or being a printer or becoming a master printer, you have to have a complete understanding of the history of the medium, whatever you are doing. Otherwise you are reinventing the wheel.”

![John Baldessari viewing René Magritte's The Treachery of Images (This is Not a Pipe) (La trahison des images [Ceci n'est pas une pipe]), 1929, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by the Mr. and Mrs. William Preston Harrison Collection, with Magritte's The Liberator, 1947, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of William Copley, in the background; artwork © C. Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York](/sites/default/files/attachments/John%20Baldessari%20in%20galleries.png)

They were candid about their attraction, however quirky, to particular artworks. John Baldessari, looking at René Magritte’s masterpiece The Treachery of Images (This is Not a Pipe) (1929), mused: “I’m curious about the morphology of the pipe and all the variants—which is what an artist does, thinks about why is one thing different than another thing.” Betye Saar recalled being drawn repeatedly to certain spaces in the museum, specifically to the Art of the Pacific galleries: “I wondered about what I wanted to do. What was it about this space and about the art in this room that really intrigued me?”

The artists make the museum, certainly, but in listening to “artists on art” we learn how the museum makes artists. Staring up at Tony Smith’s Smoke (1967, fabricated 2007), Thomas Houseago reflected on how, as a U.K.-born artist new to Los Angeles, this open-form American monument shook him to the core: “It really troubled me. . . . I was one of these programmed, European art people. But this sculpture, in some ways, was a prophetic thing for me . . . that investigation into how sculpture deals with the public and how a person looks at sculpture. . . . It’s arguing for form, it’s arguing for experiences, it’s arguing for emotional, physical complexity.”

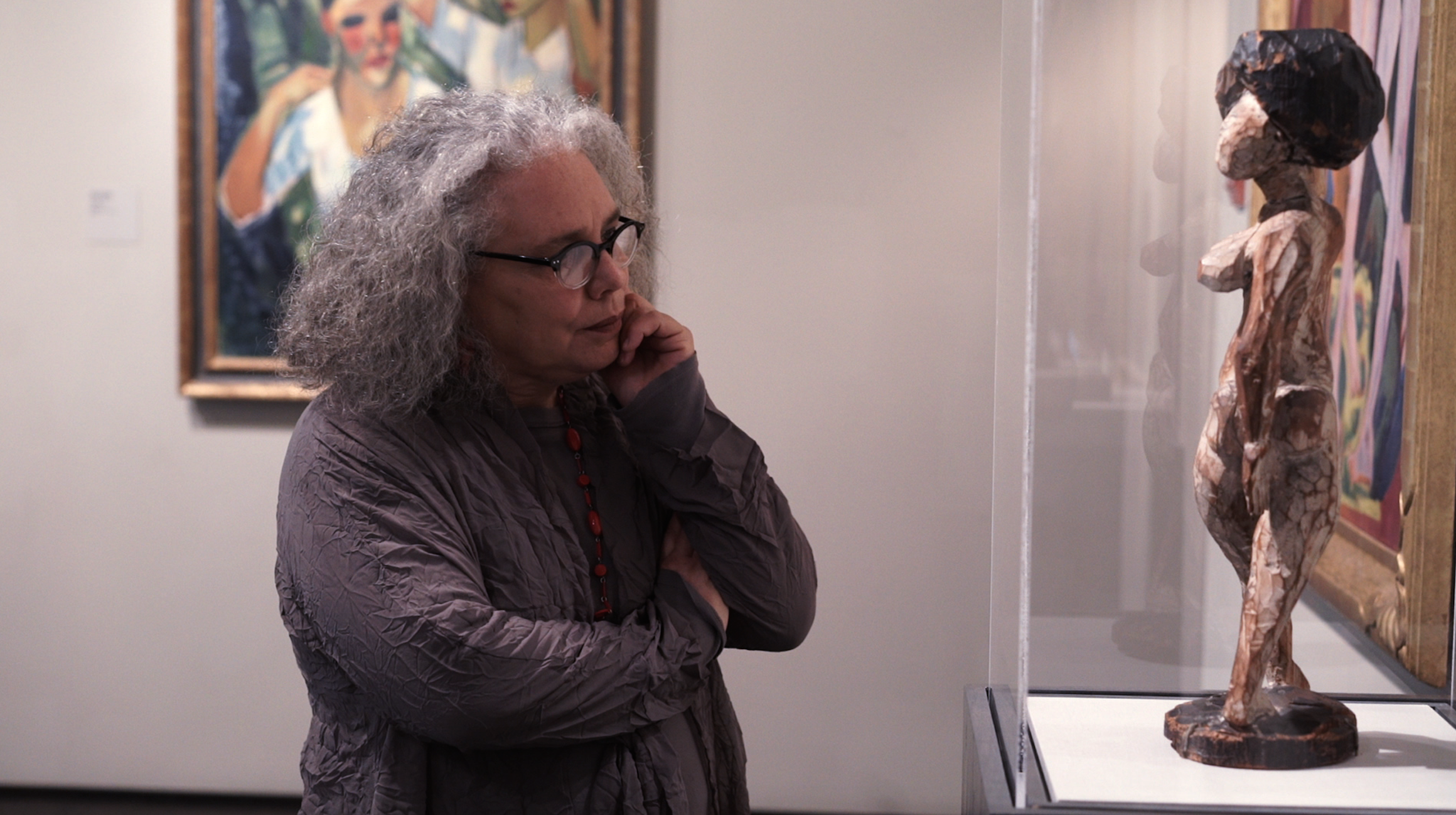

Alison Saar recollected that Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Dancer with Necklace (1910) brought pleasure back into her work after a somber period: “I saw this piece and I was just like, ‘Oh, but I’m forgetting about dance. And I’m forgetting about the joy and the beauty of life.’” In front of a Lee Friedlander portfolio, from which she had selected the photograph Statue–New Jersey (1971, printed 1973), Judy Fiskin advocated for museum-going: “I did not go to art school, I did not study photography in an organized way. . . . Because I wasn’t studying it formally, I got to just pick the ones that appealed to me.”

Intense looking has been crucial to Catherine Opie’s visitations, over many years, with other artists’ images, because they make her own more relevant to the world at large: “In relationship to my own work, I always believe in compassion and I always believe in looking at figures in terms of ideas of landscape and what it is to bear witness.” For Artists on Art, she discussed the painting Wrestlers (1899) by Thomas Eakins, which features the entwined bodies of two men at its center.

To hear these artists not only consider the big picture but also parse the details of their predecessors’ achievements in a given medium is to gain access to exceptional technical expertise. James Welling, speaking on two untitled works by Lázsló Moholy-Nagy, a photogram from 1926 and an aerial-view photograph from 1929, elucidated this artist’s “sensitivity to the conditions of the photographic”—how he elevated a relatively new technology to the status of art. Tom Knechtel guided us through the composition of a late-eighteenth-century drawing by Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Centaur Arrested in Flight, a Female Faun on His Back (c. 1759–91), pointing out that “it’s shifting, it’s disappearing” through the “evanescence” of its ink wash, and noting that “there are lots of artists of this period who can draw technically dazzling drawings but who don’t have the ability to be as moving.” Indeed, the emotional impact of viewing art is as key as art history and technique in these testimonials. Mario Ybarra, Jr. has long embraced the sculpture of Edward Kienholz for that “empathetic moment where you are inserted into the work. . . . It isn’t just a viewing experience, but an actual stepping-into experience.”

Carol needed to ask only a question or two to get the artists going. All of them were more than generous in opening up about LACMA’s permanent collection; Agnes was left with daunting amounts of footage. Her superb editing has captured, for Artists on Art, the wonderful encounter of creative personalities with extraordinary works. Facilitating a range of thoughtful perspectives on art, as well as intimacy with it (even when behind glass!), defines the museum’s mission. More videos are in the works—stay tuned, come visit, keep looking, keep making.